All God's Chillun Got Soul

The race issue is the really difficult one. Fraught with danger. It goes to the heart not just of the music but the whole of our cultural, social and political existence. But that, I think, makes it so much more important that we don’t duck the issues it throws up – even if it makes for some difficult and uncomfortable thoughts. There are many people better qualified to write about this subject than I am, but this is a personal view from the sidelines across the Atlantic.

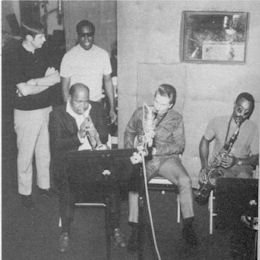

Aretha at AGP studios

Aretha at AGP studios For a middle-class white boy growing up in the mid-60s in the UK it was actually very easy. Afro-American singers were it, no question, and European artists were nowhere. Black good white bad. And it was hip too. As a lover of black music you were part of a secret world not available to your contemporaries, lost as they were in the Beatles, the Hollies and the rest of the pop universe. The appeal was part exotic, the attraction of the different culture the music represented, part fashion, but mostly it was the feel. Soul music WAS different, exciting and instantly recognisable. You just KNEW when you heard it – and American blacks were responsible for all these wonderful sounds. The key was the vocals, the emotional outpourings straight from the very heart of the performer. Just had to be black to get that feel surely.

But as time went on and I delved deeper into the music, and learnt more about the social context in which it was created, disturbing facts started creeping in to upset the adolescent certainties. Half of the MGs were white – as was a good proportion of their horn section the Mar-Keys. And the shock shown by Wilson Pickett and Laura Lee among others at recording with a bunch of rednecks in Alabama was mirrored in England. White faces had an unsettling habit of appearing in other places as well – such as the back of Oscar Toney’s superb Bell LP. What was going on? If the “feel” of the music was what mattered, how much of the Stax and Muscle Shoals soul was due to the wonderful musicians who played on the records which were cut there? Could it be that “soul” was a cultural phenomenon that could be learnt, not a racial one which came with the genes? Sacrilege!

Geater Davis at Boutwell studios

Geater Davis at Boutwell studios This prejudice in favour of black artists obscured the awkward issue of just what was “black” here. On the American model based on prejudice and segregation, anybody who wasn’t ethnically pure European qualified, even if – in the horribly revealing phrase – they could “pass for white”. But where did that definition leave one of my heroes Johnny Otis, who lived his life as a black man in the black community, even though he was born of Greek parentage as John Veliotes? This was clearly more complex than I’d previously imagined.

Why did the colour of the artist’s skin matter so much anyway? Partly it was a question of authenticity. Black sounds aimed at a black audience seemed to make the music more Afro-American. So Stax and Atlantic were more “genuine” and authoritative than say, Motown. These blithe assumptions, of course, neatly ignored the economics of the record business. In my world Berry Gordy was veering far too close to pop music rather than real soul. In the real world the fact that he had recognised that there were many more white punters than black, and tuned his business accordingly should have been a source of envy and admiration rather than the reverse.

Also the feeling that black skin was important was a clear reaction to the “rip-offs” which constituted many insipid white covers of soul tunes. Although this practise was more prevalent in the 50s – and worse artistically – it still occurred in the 60s. The most extreme examples like the Walker Brothers “My Ship Is Coming In”, the Moody Blues “Go Now” and the Beatles atrocious “Twist and Shout” still continue to grate even to this day. But I never appreciated the old adage about imitation and flattery then, and besides what about my beloved Otis R’s cut of “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction” or Aretha’s “Eleanor Rigby” or “The Weight”. Admittedly even I felt a twinge at these last two discs but these artists could do no wrong in my eyes then.

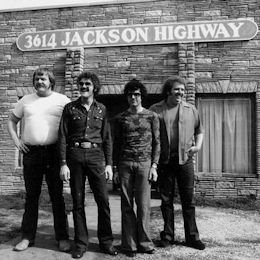

Clarence Carter at Fame studios

Clarence Carter at Fame studios A major disquieting issue related to the socio-political background to the music. Segregation was still a fact of life in the Southern states in the Golden Age, the Civil Rights movement was polarising opinion among the white community - and the hard men were far from averse to violence. In the North segregation was more of an economic factor than a political one – but none the less real for that. This was an evil and deeply despised creed but, like the rural poverty that created the blues, had an unexpected spin-off. Everybody knew that soul music came from the Church, secularised Gospel if you will, but what if it was the racial separation of spiritual life in the US that helped create all these marvellous discs? Since soul singing was learnt in the Churches, was the fact that whites had their own religious upbringing the only thing that stopped them from sounding like James Carr?

Gradually, as the Civil Rights movement in the States moved towards Black Power, I started to acknowledge that white folks existed in my artistic world. I learnt to respect the many white musicians who loved black music and who were prepared to brave the wrath of their peers by playing and singing in black styles. Or by associating with black performers, particularly in the intimidating atmosphere south of what Jerry Wexler wryly referred to as the Smith & Wesson line. Integrated bands became much more common at the end of the 60s, but at the height of the decade they were brave ventures, especially in the areas where politicians like George Wallace commanded a big following.

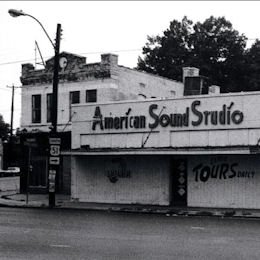

AGP studios

AGP studios But in the end it wasn’t Dusty Springfield’s well-publicised trip to Memphis, or John Mayall’s superb affinity for the blues that really opened my eyes, it was Jimi Hendrix. Here was a black star, very visible in England at the time, with a huge ego and a big fanbase amongst my contemporaries, making music I hated. He couldn’t sing a note, played the guitar in a way that made me long for Albert King, and seemed to have turned his back on the traditions of the blues and the Church that I adored, in the pursuit of white money. There had to more to music than this – and listening to Hendrix when I was forced to - I knew that I wouldn’t automatically find it in the colour of a man’s skin. An artist’s desire to create his own particular body of work was not a concept that I considered at the time – I still thought in terms of a black music “box”.

Bit by bit, via reading people like Charlie Gillett, I started widening my musical horizons. Artists like Tony Joe White, whose first album was aptly called “Black and White”, I found particularly rewarding. And swamp-pop stars like Freddie Fender, Bobby Charles and the great Joe Barry with tracks like “I’m A Fool To Care” also helped blur the racial lines. These were guys who sang soulfully without necessarily being soul singers, but it did open the way for a better understanding of the ways in which music was multi-faceted rather than one-eyed as I’d previously believed.

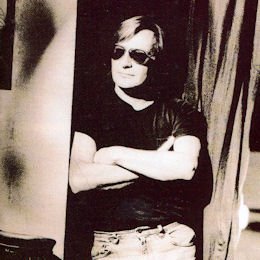

Muscle Shoals Sound studios

Muscle Shoals Sound studios This process was undoubtedly assisted as more and more soul 45s found their way into the UK. Obscurity equalled uncertainty. It was clear who was black and who was white – wasn’t it? Ben Aitken on Josie for example. A Goldwax recording so it must be collected, but what race was the singer? Jerry Woodard appeared on Dial and Argo, very largely black labels, but the sound was poppier than other 45s on the same logo. He must be white – but hang on a minute, what about his extraordinary single on Chant? The most extreme example of this was undoubtedly Eddie Hinton. His superb Capricorn album had no obvious picture of the artist on the sleeve – just a blurred outline of a black man lurking in an alley. As it turned out this was a deliberate ploy to aim the disc at the black market, but it was only when I noticed a picture of him on the back of a Boz Scaggs album (incidentally another artist with strong soulful leanings) that I could really accept he was white.

The point of all this is of course that it doesn’t really matter whether an artist is black or white. These days I’m content to admit my earlier prejudices – they may even touch a chord with one or two people reading this article – but I’ve moved a long way from the days when I’d instantly remove white records from record players at parties. The race of an artist remains an interesting factor in my assessment of a disc, but I really do try to judge a sound on it’s own artistic merit. I still listen to much more black music than white – but these days that’s an artistic preference rather than a racial one. After all, I can now even accept that I’m white myself.

Perhaps the great Dan Penn put it best:- “It’s just skin.”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Top 25 Blue Eyed Soul Winners

(A Work In Progress)

Tony Joe White

Tony Joe White

![]() Willie And Laura Mae Jones (Warner Bros)

Willie And Laura Mae Jones (Warner Bros)

A wonderfully evocative song about race relations in the Deep South beautifully rendered. Tony Joe still writes and produces some marvelous music today - particularly his minor keyed songs. Sadly his voice no longer has the range it did when "Willie And Laura Mae" was cut.

George Soule

George Soule

![]() Get Involved (Fame)

Get Involved (Fame)

One of the most incise and inventive southern writers George Soule is a multi talented musician as well as being a first rate vocalist. This track - his biggest seller - has a super irony of a white guy hitting with a plea for black involvement in the political process – great Muscle Shoals funk too. Check out George's recent CD "Take A Ride" for more of his expressive singing.

Len Wade

Len Wade

![]() It Comes And It Goes (Dial)

It Comes And It Goes (Dial)

A near perfect deep soul piece. As Len pours his heart out the falsetto shrieks are enough to raise the hairs on the back of your neck. He was a big draw in the south eastern US with his band the Tikis and more of his recordings are coming to light thanks to the efforts of Jim Lancaster at Playground studios. These tracks show just what a wonderful vocalist he was.

Delbert McClinton

Delbert McClinton

![]() Jealous Kind (Capitol)

Jealous Kind (Capitol)

Fantastic slow burn from a key blue-eyed performer. White hot R &B indeed. Every LP and CD he has cut has contained some fine soul and blues songs - mostly penned by himself. He continues to offer great singing to those who really care about southern music.

Righteous Brothers

Righteous Brothers

![]() Unchained Melody (Verve)

Unchained Melody (Verve)

Bored by this? Too poppy? REALLY listen this time to Bobby Hatfield’s extraordinary gospel vocals. Easily the most accomplished melismatic white vocal I’ve ever heard. Awesome!

Frankie Miller

Frankie Miller

![]() This Love Of Mine (Chrysalis)

This Love Of Mine (Chrysalis)

Scotland’s finest in full-on Otis Redding mode with a slow deep ballad. Miller was consistently the most soulful vocalist Britain has ever produced. Sadly he was struck down with a severe brain haemorrage in the 1990s but is making very slow progress back to full health. We wish him well.

Lindell Hill

Lindell Hill

![]() Remone /

Remone / ![]() Used To Be Love (Arch)

Used To Be Love (Arch)

Astonishing double sided 45. Pickett style vocals and a Memphis production credit to Steve Cropper have given this one legendary status.

Average White Band

Average White Band

![]() A Love Of Your Own (Atlantic)

A Love Of Your Own (Atlantic)

Can’t leave out the AWB from this list. A band that genuinely broke down the racial barriers here showing Hamish Stuart’s great pipes.

Gee Gee Shinn

Gee Gee Shinn

![]() Devil Of A Girl (Montel Michelle)

Devil Of A Girl (Montel Michelle)

Louisiana had more white soul singers than any other state – why? Many of the singers were heavily influenced by Otis Redding and Bobby Bland. This is about as good as they come, a wonderful blues ballad superbly sung by Shinn, backed by the best band in Louisiana - the Boogie Kings.

Troy Seals

Troy Seals

![]() Mama Hold My hand (Rising Sons)

Mama Hold My hand (Rising Sons)

Harrowing Vietnam tale from a guy best known as a Nashville session guitarist – you’d never guess it though.

Dusty Springfield

Dusty Springfield

![]() Son Of A Preacher Man (Atlantic)

Son Of A Preacher Man (Atlantic)

Some people's choice as the best white female voclaist. I'm not sure I'd go that far but on her "Memphis" LP she cut some fine soul. This is probably the pick of them - breathy, panting vocals over a song of lust beautifully played by the crack AGP band.

Southside Johnny & the Asbury Jukes

Southside Johnny & the Asbury Jukes

![]() Little Girl So Fine (Epic)

Little Girl So Fine (Epic)

Arguably the best of the retro groups with a lovely evocation of early 60s Big Apple baion magic.

Johnny Daye

Johnny Daye

![]() Stay Baby Stay (Stax)

Stay Baby Stay (Stax)

Hoarse emotional pleading from an Otis protégé.

Timi Yuro

Timi Yuro

![]() I’m Movin’ On (Part 1) (Liberty)

I’m Movin’ On (Part 1) (Liberty)

Close your eyes and listen to an astonishing feat of bluesy testifying. Is it Esther Phillips? Big Maybelle? No, a tiny white chick from the Windy City, now sadly no longer with us.

Eddie Hinton

Eddie Hinton

![]() Get Off In It (Capricorn)

Get Off In It (Capricorn)

Eddie in a reflective mood. Before his voice was wrecked by his hard-driving lifestyle. “Very Extremely Dangerous” remains the touchstone of blue-eyed soul.

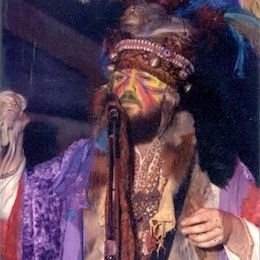

Dr. John

Dr. John

![]() A Quitter Never Wins (Atco)

A Quitter Never Wins (Atco)

Classic slab of funk from Crescent City keyboard wizard steeped in black music who led the city’s first integrated band in the 60s.

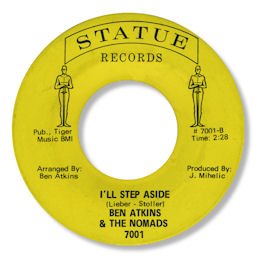

Ben Atkins & the Nomads

Ben Atkins & the Nomads

![]() I’ll Step Aside (Statue)

I’ll Step Aside (Statue)

Another deep winner from a forgotten figure who also cut as Big Ben for Enterprise.

Boz Scaggs

Boz Scaggs

![]() Look What I’ve Got To Come Home To (Atlantic)

Look What I’ve Got To Come Home To (Atlantic)

From his first Muscle Shoals LP, a soulful country song beautifully arranged. Scaggs remained a good friend to black music throughout his long and distinguished career.

Jerry Woodard

Jerry Woodard

![]() Something I Ain’t Never Had (Chant)

Something I Ain’t Never Had (Chant)

Growling intensity and fierce emotions – everything you always need in the deepest of soul.

Dan Penn

Dan Penn

![]() I Need Someone (MGM)

I Need Someone (MGM)

Not a great song – but his best vocal performance from the 60s until his Muscle Shoals demos finally see the light of day.

Jeannie Greene

Jeannie Greene

![]() Sure As Sin (Atco)

Sure As Sin (Atco)

Marlin Greene played a big part in early Muscle Shoals music - engineer/guitarist to Quin Ivy, he wrote many fine songs especially in partnership with a young Eddie Hinton. His wife Jeannie was a stalwart session singer in the MS studios in the 60s. This is her best 45 from the Golden Age. Quite superb.

Mink De Ville

Mink De Ville

![]() Just To Walk That Little Girl Home (Capitol)

Just To Walk That Little Girl Home (Capitol)

Ignoring Willie’s garage anthems is a must – but his ballads are something else. The best evocation of the vanished world of Pomus/Shuman I know. His later New Orleans music is well worth digging into as well. Sadly he passed away in 2009.

Delaney & Bonnie

Delaney & Bonnie

![]() Dirty Old Man (Warner Bros)

Dirty Old Man (Warner Bros)

Bonnie Bramlett was the voice of the duo. Here she shows off her gospel chops to wonderful sneering effect. Still going very strong I’m pleased to say.

Charlie Rich

Charlie Rich

![]() Feel Like Goin’ Home (Acoustic Demo)

Feel Like Goin’ Home (Acoustic Demo)

Some fans’ choice as THE white soulman. This is a tour-de-force of almost unbearable emotional impact – just Charlie and his piano. (Thanks Joe.)

Fabulous Thunderbirds

Fabulous Thunderbirds

![]() Wasted Tears (Epic)

Wasted Tears (Epic)

Usually a fine blues based band the T-Birds cut one very soulful LP (“Hot Number”) with the Memphis Horns. This is the cream cut – lead Kim Wilson’s phrasing is always a joy to listen to.

Thanks to "Billy" for a correction to the para on Jeanie Greene.