DEEP SOUL : TOWARDS A DEFINITION

by Pete Nickols

It was Ben E. King who musically asked ”What Is Soul?”. Like all categorizations it was a term that only came into being long after the recording of what are now regarded as the first examples of the genre. Indeed King’s record wasn’t cut until 1966, some four to five years after the appearance of those early examples. A style is perceived to exist only when similarities in a body of music (which has already inevitably existed for some time) are first noted. So how did ‘deep-soul’ come about and what exactly is this sub-genre? Well, of course, it didn’t ‘come about’ at all; rather it is simply a name given to a particular style of soul music. So what is it that makes a particular soul record truly ‘deep’? What gives it that all-important ‘depth’? Well, I do believe that the pace of the performance usually has to be slow (examples of even mid-paced but still genuinely deep soul records are quite rare); but the real answer surely lies in the emotional content of the recording. In all of the best soul music, ‘feeling’ is very important. In the deep-soul sub-genre, rather than there being merely a need for ‘feeling’, there is a need for genuine, or at least genuine-sounding, ‘emotion’.

It was Ben E. King who musically asked ”What Is Soul?”. Like all categorizations it was a term that only came into being long after the recording of what are now regarded as the first examples of the genre. Indeed King’s record wasn’t cut until 1966, some four to five years after the appearance of those early examples. A style is perceived to exist only when similarities in a body of music (which has already inevitably existed for some time) are first noted. So how did ‘deep-soul’ come about and what exactly is this sub-genre? Well, of course, it didn’t ‘come about’ at all; rather it is simply a name given to a particular style of soul music. So what is it that makes a particular soul record truly ‘deep’? What gives it that all-important ‘depth’? Well, I do believe that the pace of the performance usually has to be slow (examples of even mid-paced but still genuinely deep soul records are quite rare); but the real answer surely lies in the emotional content of the recording. In all of the best soul music, ‘feeling’ is very important. In the deep-soul sub-genre, rather than there being merely a need for ‘feeling’, there is a need for genuine, or at least genuine-sounding, ‘emotion’.

There is a commercial driving-force behind the production of popular music records generally – with soul records being no exception – and it therefore has to be acknowledged, whether we like it or not, that most vocal ‘emotion’ expressed on a soul recording will be contrived. Soul vocalists might sometimes draw on personal past experiences but they will still rely primarily on their interpretive vocal qualities to see them through. It is extremely rare for an artist to express nothing but genuine emotion created within them for the first time by the very content of the song they are singing. Exceptions which prove this rule would be Betty LaVette’s anguished plea “Let Me  Down Easy” (Calla 102) to a guy whom she really loved who was backing out of their affair; Irma Thomas’ self-penned post-marital-break-up cry-for-help “Wish Someone Would Care” (Imperial 66013); and Mabel John’s “Your Good Thing (Is About To End)” (Stax 192), a song written for her after she had recounted how she had stumbled upon her own husband making love to another woman. Similarly, a number of Linda Jones’ Turbo recordings seem to reflect the increasing intensity of pain and suffering she was then experiencing as her ultimately terminal diabetes condition ironically ‘helped’ her create soul performances which were almost frightening in their unbridled intensity. However, if deep-soul records only emerged when such personally intense traumas were being experienced, we would be able to count the number of such recordings merely on the fingers of our hands.

Down Easy” (Calla 102) to a guy whom she really loved who was backing out of their affair; Irma Thomas’ self-penned post-marital-break-up cry-for-help “Wish Someone Would Care” (Imperial 66013); and Mabel John’s “Your Good Thing (Is About To End)” (Stax 192), a song written for her after she had recounted how she had stumbled upon her own husband making love to another woman. Similarly, a number of Linda Jones’ Turbo recordings seem to reflect the increasing intensity of pain and suffering she was then experiencing as her ultimately terminal diabetes condition ironically ‘helped’ her create soul performances which were almost frightening in their unbridled intensity. However, if deep-soul records only emerged when such personally intense traumas were being experienced, we would be able to count the number of such recordings merely on the fingers of our hands.

No, there is nothing wrong with ‘contrived’ emotion on a record if it is done well. It is no different to a fine emotional acting performance on stage or screen even if the actor may not be personally used to experiencing the kind of deep-seated feelings he or she is being asked to convey. The ‘good’ deep-soul singer is capable of precisely the same trick, leaving the end product with that vital, authentic-sounding emotional content. The best of such singers don’t even have to try particularly hard to pull the trick – their natural interpretive qualities will see to it that their ‘deep’ performances achieve the desired goal.

What of the lyrics of the deep-soul song? Are they important? Well, lyrics in most non-repetitive soul-songs are surely important and where the soul is of the ‘storyline’ variety (which is also often - but not always - ‘deep’) they are surely of paramount importance, since the finest story ever told will mean absolutely nothing if not conveyed both clearly and interestingly. So the answer is that if the lyrics per se form an important part of the emotional content of the song, then they will be fundamental to its success as an example of deep-soul; but if virtually all the emotional content is contained, say, in the singer’s interpretation and the empathetic instrumental musical arrangement, then the words themselves may have little significance. Even so, the performance will still come across as genuinely ‘deep’. There are soul singers, singing with the right blend of musicians, to a suitably-styled slow-paced melody, who – if they deliberately set out to do so – could simply sing the telephone directory and still vocally ‘deliver’ in such an emotively soulful way that the end-product would come across as ‘deep’. Solomon Burke, Spencer Wiggins, James Carr, O.V. Wright, Candi Staton, Jean Wells, Betty LaVette and Betty Harris are among the better-known examples who spring most readily to mind – and doubtless there are many more, including actual soul legends like Sam Cooke, Jackie Wilson and Aretha Franklin who, whilst not always making truly deep secular recordings (because of their acquired ‘crossover’ appeal), nonetheless were clearly capable of the required high degree of emotional vocal interpretation and intensity.

What of the lyrics of the deep-soul song? Are they important? Well, lyrics in most non-repetitive soul-songs are surely important and where the soul is of the ‘storyline’ variety (which is also often - but not always - ‘deep’) they are surely of paramount importance, since the finest story ever told will mean absolutely nothing if not conveyed both clearly and interestingly. So the answer is that if the lyrics per se form an important part of the emotional content of the song, then they will be fundamental to its success as an example of deep-soul; but if virtually all the emotional content is contained, say, in the singer’s interpretation and the empathetic instrumental musical arrangement, then the words themselves may have little significance. Even so, the performance will still come across as genuinely ‘deep’. There are soul singers, singing with the right blend of musicians, to a suitably-styled slow-paced melody, who – if they deliberately set out to do so – could simply sing the telephone directory and still vocally ‘deliver’ in such an emotively soulful way that the end-product would come across as ‘deep’. Solomon Burke, Spencer Wiggins, James Carr, O.V. Wright, Candi Staton, Jean Wells, Betty LaVette and Betty Harris are among the better-known examples who spring most readily to mind – and doubtless there are many more, including actual soul legends like Sam Cooke, Jackie Wilson and Aretha Franklin who, whilst not always making truly deep secular recordings (because of their acquired ‘crossover’ appeal), nonetheless were clearly capable of the required high degree of emotional vocal interpretation and intensity.

The requirement for emotional intensity means that it is hard to imagine a wholly instrumental deep-soul recording but that absolutely does not mean that the instrumental backdrop behind the vocalist is unimportant. Indeed a fine vocal performance can be all but negated by a poor, unsympathetic instrumental backing or an inappropriate arrangement. The reverse can sometimes partly apply, in that a fine arrangement emotively performed by fine musicians can elevate to a higher plane what might otherwise have been merely an ‘average’ performance. However, it is clear that the very best deep-soul performances almost always successfully combine both great singing with impressively empathetic playing. This is why certain studios who regularly used musicians who could consistently offer that high degree of empathy achieved legendary status amongst soul, and especially deep-soul, fans – studios like Fame and Quinvy, of course, in North West Alabama, like Columbia and Woodland in Nashville, like Stax, American and Phillips in Memphis and, somewhat later, like Malaco in Jackson, Mississippi. But deep-soul wasn’t just the prerogative either of these particular southern studios or, indeed, of the South as a whole; many wonderful individual examples of the sub-genre emerged from all kinds of studios both in the South and the North, though they were often the smaller ones which specialised in the less overtly commercial product and which would be more likely to be used by the also small, essentially ‘local’, labels. Again exceptions exist – even crossover-fixated Motown issued deep sides by the likes of Yvonne Fair (“It Should Have Been Me” on Motown 1323 and 1384) and Brenda Holloway (“Every Little Bit Hurts” (Tamla 54094), while some major labels picked up independent or small-label ‘deep’ productions for wider distribution. In the North, Bert Berns created gems for the likes of Solomon Burke for Atlantic, Betty Harris for Jubilee, Garnet Mimms for UA and Freddie Scott, Erma Franklin and other artists for his own “Shout” roster.

The requirement for emotional intensity means that it is hard to imagine a wholly instrumental deep-soul recording but that absolutely does not mean that the instrumental backdrop behind the vocalist is unimportant. Indeed a fine vocal performance can be all but negated by a poor, unsympathetic instrumental backing or an inappropriate arrangement. The reverse can sometimes partly apply, in that a fine arrangement emotively performed by fine musicians can elevate to a higher plane what might otherwise have been merely an ‘average’ performance. However, it is clear that the very best deep-soul performances almost always successfully combine both great singing with impressively empathetic playing. This is why certain studios who regularly used musicians who could consistently offer that high degree of empathy achieved legendary status amongst soul, and especially deep-soul, fans – studios like Fame and Quinvy, of course, in North West Alabama, like Columbia and Woodland in Nashville, like Stax, American and Phillips in Memphis and, somewhat later, like Malaco in Jackson, Mississippi. But deep-soul wasn’t just the prerogative either of these particular southern studios or, indeed, of the South as a whole; many wonderful individual examples of the sub-genre emerged from all kinds of studios both in the South and the North, though they were often the smaller ones which specialised in the less overtly commercial product and which would be more likely to be used by the also small, essentially ‘local’, labels. Again exceptions exist – even crossover-fixated Motown issued deep sides by the likes of Yvonne Fair (“It Should Have Been Me” on Motown 1323 and 1384) and Brenda Holloway (“Every Little Bit Hurts” (Tamla 54094), while some major labels picked up independent or small-label ‘deep’ productions for wider distribution. In the North, Bert Berns created gems for the likes of Solomon Burke for Atlantic, Betty Harris for Jubilee, Garnet Mimms for UA and Freddie Scott, Erma Franklin and other artists for his own “Shout” roster.

However whilst deep-soul nerds will argue all day about the relative merits of certain studios, locations, musicians and producers, the origin of the recording is not what is important per se. Rather like the fervent UK ‘northern’ all-niter fan looking for that special rhythm and ‘beat’, the deep-soul fan is essentially looking for that gut-bucket anguish, that ‘wrist-slashing’ desolation, that spare, spine-tingling crie de coeur on record which, for him or her, indeed does define deep-soul.

One thing is for sure – a deep-soul record demands - and from lovers of the sub-genre immediately gets - attention! In no way could it ever be regarded as wallpaper music. Non-soul-lovers will probably hate it and want to distance themselves from it almost immediately. Deep-soul lovers will want to root their attention to it – never mind the spouse, kids, football match, TV etc.; if a favourite deep-soul record gets put on the turntable (or, these days, more likely the CD or even MP3 player), the deep-soul fan will be lost to everything else until it inevitably ends in that almost mystical ‘fade’, such an ending merely leaving the devoted listener wanting more, wishing the engineer had kept his trigger-finger off the control board for a few more precious seconds; but then, maybe, just maybe, it would be nice to think that that same engineer had been forced merely by track-length considerations to arbitrarily call a halt to the proceedings, if only to prevent the emotionally-involved vocalist carrying on all night and day like some half-demented black Pentecostalist well and truly ‘in the spirit’.

One thing is for sure – a deep-soul record demands - and from lovers of the sub-genre immediately gets - attention! In no way could it ever be regarded as wallpaper music. Non-soul-lovers will probably hate it and want to distance themselves from it almost immediately. Deep-soul lovers will want to root their attention to it – never mind the spouse, kids, football match, TV etc.; if a favourite deep-soul record gets put on the turntable (or, these days, more likely the CD or even MP3 player), the deep-soul fan will be lost to everything else until it inevitably ends in that almost mystical ‘fade’, such an ending merely leaving the devoted listener wanting more, wishing the engineer had kept his trigger-finger off the control board for a few more precious seconds; but then, maybe, just maybe, it would be nice to think that that same engineer had been forced merely by track-length considerations to arbitrarily call a halt to the proceedings, if only to prevent the emotionally-involved vocalist carrying on all night and day like some half-demented black Pentecostalist well and truly ‘in the spirit’.

Sir Shambling and his valiant contributors have provided within these web-pages (and especially within the Artist Index section) some superb examples of deep-soul, often by artists who are little-known and may have recorded only a single 45 (or no more than a handful) in their limited ‘careers’. In addition such information as is known about them accompanies the sound files. Here are a few more examples for you. Turn up the Media Player, turn down the lights, put the rest of the world on ‘hold’ and ENJOY!

Eddie Holloway ![]() I Had A Good Time (Gem 102).

I Had A Good Time (Gem 102).

Some deep-soul records are just so intense they seem to ‘eat their way into you’. A prime example (and one of my all-time favourites) is surely Eddie Holloway’s Gem 102 side

Some deep-soul records are just so intense they seem to ‘eat their way into you’. A prime example (and one of my all-time favourites) is surely Eddie Holloway’s Gem 102 side ![]() I Had A Good Time. This might seem a cheery title for what is a truly dark, brooding, ominous piece of deep-soul but the lyric quickly makes it plain that Eddie had a good time but now he’s “down”.

I Had A Good Time. This might seem a cheery title for what is a truly dark, brooding, ominous piece of deep-soul but the lyric quickly makes it plain that Eddie had a good time but now he’s “down”.

Tremendously soulful vocal dexterity is the mark of many a fine deep recording but, frankly, not here. This is an example of the small sub-genre where the musical backdrop is, if anything, almost more significant than the vocal. Throughout the main (pre-climax) part of the performance, Holloway uses an almost-spoken deep baritone vocal delivery which nevertheless includes more than enough emotive inflexion to stamp genuine ‘soul’ on the decidedly morose proceedings; but the sombre-mood-inducing ambiance of the piece is chiefly down to the sonorous, brooding intensity of the baritone-sax-led brass which is more than just mournful, it’s almost funerial, whilst some impressive guitar work keeps the slow-paced melody going and also offers up some nice fills. The drumming is strong too throughout, becoming increasingly well to the fore as the song reaches its dramatic climax, at which point we do get some well-delivered, impassioned ad-libbed cries de coeur from Holloway plus a potent final anguished scream-come-shout into the fade.

If ever a record was released on an aptly-named label this was it. A real deep-soul ‘gem’ for sure.

If ever a record was released on an aptly-named label this was it. A real deep-soul ‘gem’ for sure.

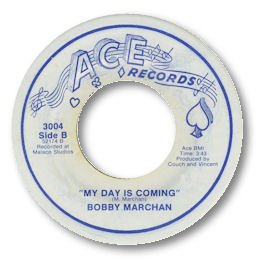

Bobby Marchan ![]() Meet Me In Church (Cameo 453) and

Meet Me In Church (Cameo 453) and ![]() My Day Is Coming (Ace 3004)

My Day Is Coming (Ace 3004)

Some deep-soul songs are so good that they attract many fine covers (“The Dark End Of The Street”, “When Something Is Wrong With My Baby” and “A Change Is Gonna Come” are examples which come most readily to mind); but the Joe Tex-penned “Meet Me In Church” has also attracted a few good singers in its time. Joe’s own Dial 3007 1962 Nashville-recorded original of this song is undoubtedly one of the finest early examples of country-meets-gospel soul music; but with its inevitably rather dated country-based instrumental accompaniment provided by, wait for it, ‘Bubber Sud & Band’, together with it’s not very appropriate almost mid-paced rhythm, it has to be just about ruled out of the really ‘deep’ soul-stakes, despite the fine subject-underlining gospelly chorus in evidence behind Tex at various points in the song.

Some deep-soul songs are so good that they attract many fine covers (“The Dark End Of The Street”, “When Something Is Wrong With My Baby” and “A Change Is Gonna Come” are examples which come most readily to mind); but the Joe Tex-penned “Meet Me In Church” has also attracted a few good singers in its time. Joe’s own Dial 3007 1962 Nashville-recorded original of this song is undoubtedly one of the finest early examples of country-meets-gospel soul music; but with its inevitably rather dated country-based instrumental accompaniment provided by, wait for it, ‘Bubber Sud & Band’, together with it’s not very appropriate almost mid-paced rhythm, it has to be just about ruled out of the really ‘deep’ soul-stakes, despite the fine subject-underlining gospelly chorus in evidence behind Tex at various points in the song.

From 1967, Don Varner’s very good unissued-at-the-time version (which had been due for release on Veep in 1968) undoubtedly benefits from its Quinvy Studio origins and is certainly ‘deeper’ than Tex’s recording from some five years earlier. Varner’s cut first appeared on CD in 1996 on US Overture’s “Tear Stained Soul” (34901-2), then on Don’s own Retour logo in 2001 (“Heart And Soul- Volume 2” – #2001-4), and more recently on Clive Richardson’s 2005 Shout RPMSH 299 CD “Finally Got Over!”.

From 1968, Solomon Burke’s Atlantic 2527 interpretation was arguably even better, cut in Memphis by the Bishop Of Soul, who was naturally very at home with this gospelly styled piece, which included some lovely guitar runs and fills from the incomparable Reggie Young. Although Solomon virtually introduced country-soul to the R&B charts with his 1961 version of “Just Out Of Reach”, the ever-sanctified but long-citified Burke proves not quite as adept as a Tex or a Varner at infusing “Meet Me In Church” with its inherent country-feel. Nonetheless this is easily a good-enough piece of deep-soul to have been rewarded with inclusion on these web-pages; but it has already seen reissue on CD by Rhino, Sequel and others and, for me, the very best deep country-soul interpretation of Tex’s song rests with that sometime female impersonator, and one-time Louisiana-based Huey Smith ‘Clown’, Bobby Marchan, who was recording for Buddy Killen’s Dial imprint, along with the said Joe Tex, as early as 1964. Killen obviously also had a tie up, though, with the more widely-distributed Philadelphia-based Cameo label, as Marchan’s 1967 version of Tex’s song (cut around the time of Varner’s but pre-dating Burke’s) was the singer’s third Cameo release (#453), having had a minor R&B hit a year earlier with ”Shake Your Tambourine” (#429). Of course as much as seven years earlier, in pre-soul 1960, Bobby had enjoyed a No.1 R&B hit with his cover of Big Jay McNeely/Sonny Warner’s “There Is Something On Your Mind”.

From 1968, Solomon Burke’s Atlantic 2527 interpretation was arguably even better, cut in Memphis by the Bishop Of Soul, who was naturally very at home with this gospelly styled piece, which included some lovely guitar runs and fills from the incomparable Reggie Young. Although Solomon virtually introduced country-soul to the R&B charts with his 1961 version of “Just Out Of Reach”, the ever-sanctified but long-citified Burke proves not quite as adept as a Tex or a Varner at infusing “Meet Me In Church” with its inherent country-feel. Nonetheless this is easily a good-enough piece of deep-soul to have been rewarded with inclusion on these web-pages; but it has already seen reissue on CD by Rhino, Sequel and others and, for me, the very best deep country-soul interpretation of Tex’s song rests with that sometime female impersonator, and one-time Louisiana-based Huey Smith ‘Clown’, Bobby Marchan, who was recording for Buddy Killen’s Dial imprint, along with the said Joe Tex, as early as 1964. Killen obviously also had a tie up, though, with the more widely-distributed Philadelphia-based Cameo label, as Marchan’s 1967 version of Tex’s song (cut around the time of Varner’s but pre-dating Burke’s) was the singer’s third Cameo release (#453), having had a minor R&B hit a year earlier with ”Shake Your Tambourine” (#429). Of course as much as seven years earlier, in pre-soul 1960, Bobby had enjoyed a No.1 R&B hit with his cover of Big Jay McNeely/Sonny Warner’s “There Is Something On Your Mind”.

But on Marchan’s magnificently-sung ![]() Meet Me In Church I especially like the very appropriate slow pace, as well as the good, sympathetic choir, the occasional use of chimes and the churchy piano, all of which come together to create exactly the right ‘feel’ for a soul-record of this title; and there’s some fine guitar-work too which almost sounds like Young again but is more likely to be thanks to a talented Nashville studio player. However, it’s Marchan’s clear high-tenor tones and terrific empathy with the inherent beauty of the lyric which together put his version at the head of the pack for me.

Meet Me In Church I especially like the very appropriate slow pace, as well as the good, sympathetic choir, the occasional use of chimes and the churchy piano, all of which come together to create exactly the right ‘feel’ for a soul-record of this title; and there’s some fine guitar-work too which almost sounds like Young again but is more likely to be thanks to a talented Nashville studio player. However, it’s Marchan’s clear high-tenor tones and terrific empathy with the inherent beauty of the lyric which together put his version at the head of the pack for me.

We shouldn’t leave Bobby Marchan’s deep-soul heritage, though, without mention also of the gorgeous self-penned

We shouldn’t leave Bobby Marchan’s deep-soul heritage, though, without mention also of the gorgeous self-penned ![]() My Day is Coming, recorded much later, in 1974, for Johnny Vincent’s then-still-going-strong Ace imprint (Ace 3004) – a deep winner, cut (allegedly with New Orleans hero James Booker in attendance) at Malaco’s Jackson, Mississippi studio, and a track to rival just about anything which came out of this only-just-pre-disco-era. The track appeared on Westside’s 1998 CD “Clown Jewels” (WESM 592) and later, in 2000, on the same label’s “Curiosities” double-set (WESD 208).

My Day is Coming, recorded much later, in 1974, for Johnny Vincent’s then-still-going-strong Ace imprint (Ace 3004) – a deep winner, cut (allegedly with New Orleans hero James Booker in attendance) at Malaco’s Jackson, Mississippi studio, and a track to rival just about anything which came out of this only-just-pre-disco-era. The track appeared on Westside’s 1998 CD “Clown Jewels” (WESM 592) and later, in 2000, on the same label’s “Curiosities” double-set (WESD 208).

Sadly, following a fight with cancer, Bobby Marchan died aged 69 on 5 December 1999 in his beloved adopted home of New Orleans (he had been born Oscar James Gibson on 30 April 1930 in Youngstown, Ohio).

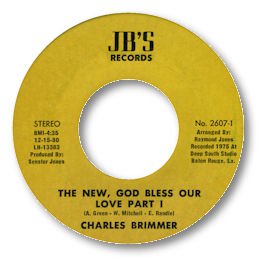

Charles Brimmer ![]() God Bless Our Love (Parts 1 & 2 from Chelsea LP CHL 508)

God Bless Our Love (Parts 1 & 2 from Chelsea LP CHL 508)

Willie Dixon ![]() God Blessed Our Love (Ace 3008)

God Blessed Our Love (Ace 3008)

Charles Allen ![]() God Blessed Our Love (Dash 5017)

God Blessed Our Love (Dash 5017)

Another much-recorded deep-soul song (this time in the gospel-soul sub-genre) is Al Green, Willie Mitchell and Earl Randle’s lay-back paen to a strong meaningful relationship, “God Blessed Our Love”, which Mitchell included on Green’s 1974 album “Al Green Explores Your Mind”. On Green's original he offers a semi-spoken intro, some good use of emotive melisma and some telling inter-line quasi-preaching, while a full string backdrop and appropriately gospelly small-chorus add to the general appeal. Mitchell chose not to use the track on a Green 45, presumably because he had plenty of other songs ‘in the can’ by his crossover-hit-soulman which had perhaps more commercial potential and were also less close to pure gospel.

Another much-recorded deep-soul song (this time in the gospel-soul sub-genre) is Al Green, Willie Mitchell and Earl Randle’s lay-back paen to a strong meaningful relationship, “God Blessed Our Love”, which Mitchell included on Green’s 1974 album “Al Green Explores Your Mind”. On Green's original he offers a semi-spoken intro, some good use of emotive melisma and some telling inter-line quasi-preaching, while a full string backdrop and appropriately gospelly small-chorus add to the general appeal. Mitchell chose not to use the track on a Green 45, presumably because he had plenty of other songs ‘in the can’ by his crossover-hit-soulman which had perhaps more commercial potential and were also less close to pure gospel.

However, that didn’t stop Crescent City native, Charles Brimmer cutting a very telling cover version the following year for Senator Jones while linked to Jones’ Hep ‘Me concern and this did indeed not only see single release as ![]() God Bless Our Love when leased out to the Chelsea label (#3017) but peaked at No.45 on the R&B chart in the summer of 1975, returning, on reissue, for a further low chart placing in 1977.

God Bless Our Love when leased out to the Chelsea label (#3017) but peaked at No.45 on the R&B chart in the summer of 1975, returning, on reissue, for a further low chart placing in 1977.

Brimmer’s 45 split his performance into Parts 1 and 2, one Part on each side, but the full unbroken track (which features Brimmer’s sublime soul-preaching throughout and is not in any way artificially extended by an instrumental passage) was included in its 8 minute-long entirety on Brimmer’s 1975 Chelsea CHL 508 album “Expression Of Soul”.

Brimmer’s 45 split his performance into Parts 1 and 2, one Part on each side, but the full unbroken track (which features Brimmer’s sublime soul-preaching throughout and is not in any way artificially extended by an instrumental passage) was included in its 8 minute-long entirety on Brimmer’s 1975 Chelsea CHL 508 album “Expression Of Soul”.

To me, Brimmer’s performance is superb and certainly superior to Green’s admittedly fine original. The sparse but telling churchy organ and drum support behind Charles’ ethereal vocal only increases the gospel feel while the lack, this time, of any string ‘sweetening’ puts Brimmer’s oh-so-interpretive vocal more to the fore than Green’s. Brimmer’s 45 version of Part 1 saw UK release on Gary Cape’s Special Agent label (SPY 9005). Brimmer followed his hit single by trying a similar ‘trick’ with a fine cover for Chelsea (#3030) of Jerry Butler’s “I Stand Accused” (also included on Cape’s Special Agent 45 release) and was unlucky to see that track miss out on the R&B charts. Sadly, further Chelsea releases also failed to make a commercial impression.

Possibly just pre-dating Brimmer’s cover of Al Green’s song was another fine version Of

Possibly just pre-dating Brimmer’s cover of Al Green’s song was another fine version Of ![]() God Blessed Our Love, issued as a March 1975 release on Johnny Vincent’s Ace label (#3008) by Willie Dixon. Vincent had co-produced this cut with Tommy Couch at the latter’s Malaco studio and wanted an acetate and master pressed up quickly as “John Richbourg will be over to pick it up” (to quote a Vincent memo of the time). Clearly unrelated to the famous late blues singer, bass player and Chess-label-Mr-Fix-It-Man of the same name, this particular Willie Dixon shares a credit on the ‘B’ side of his 45 with Bobby Marchan on what is actually a straightforward reissue of Marchan’s solo-credited “My Day Is Coming” (from Ace 3004), this time somehow renamed “My Days Are Coming”. Dixon’s extremely creditable performance of Green’s song appeared on CD in 2000 via Westside’s “Curiosities” WESD 208 double set.

God Blessed Our Love, issued as a March 1975 release on Johnny Vincent’s Ace label (#3008) by Willie Dixon. Vincent had co-produced this cut with Tommy Couch at the latter’s Malaco studio and wanted an acetate and master pressed up quickly as “John Richbourg will be over to pick it up” (to quote a Vincent memo of the time). Clearly unrelated to the famous late blues singer, bass player and Chess-label-Mr-Fix-It-Man of the same name, this particular Willie Dixon shares a credit on the ‘B’ side of his 45 with Bobby Marchan on what is actually a straightforward reissue of Marchan’s solo-credited “My Day Is Coming” (from Ace 3004), this time somehow renamed “My Days Are Coming”. Dixon’s extremely creditable performance of Green’s song appeared on CD in 2000 via Westside’s “Curiosities” WESD 208 double set.

A certain John Ridley gave the first CD release to what I still regard as my personal favourite ‘short’ version of God Blessed Our Love, yet another 1975 cover, by Charles Allen on Henry Stone’s Miami-based TK subsidiary Dash (# 5017). Charles’ recording featured on the fine 1995 CD compilation “Deep Down In Florida – TK Deep Soul” (Sequel NEMCD 721). Rightly, John describes Charles’ version as much less polished than Green’s but does give due credit to the great effect achieved from Allen’s impassioned delivery. Amen to that! Here it’s a guitar and gospelly chorus which provide the sparse initial backing behind Allen’s clearly heartfelt vocal, although the strings soon also enter the fray ala the Green original, adding a nice degree of pathos and rounding out a genuinely top-drawer performance.

A certain John Ridley gave the first CD release to what I still regard as my personal favourite ‘short’ version of God Blessed Our Love, yet another 1975 cover, by Charles Allen on Henry Stone’s Miami-based TK subsidiary Dash (# 5017). Charles’ recording featured on the fine 1995 CD compilation “Deep Down In Florida – TK Deep Soul” (Sequel NEMCD 721). Rightly, John describes Charles’ version as much less polished than Green’s but does give due credit to the great effect achieved from Allen’s impassioned delivery. Amen to that! Here it’s a guitar and gospelly chorus which provide the sparse initial backing behind Allen’s clearly heartfelt vocal, although the strings soon also enter the fray ala the Green original, adding a nice degree of pathos and rounding out a genuinely top-drawer performance.

Beverly Crosby ![]() Have We Become Prisoners (Magic People Records 40)

Have We Become Prisoners (Magic People Records 40)

This superb example of lay-back storyline deep-soul sees Beverly expounding her views about why her and her never-named partner’s relationship is now essentially over. The title, however, sums up her own suggested reason why nevertheless they continue to stay together despite the obviously unsatisfactory situation, namely “have we (let ourselves) become prisoners of our own selfishness?” She is seeking a response from her partner because she thinks that, even though there is clearly nothing meaningful left in their relationship, if they can both accept this reason for their problems, there is still a real chance they can at least be adult about why they no longer want each other and can then perhaps finally take the difficult, yet ultimately only sensible decision to go their separate ways.

This superb example of lay-back storyline deep-soul sees Beverly expounding her views about why her and her never-named partner’s relationship is now essentially over. The title, however, sums up her own suggested reason why nevertheless they continue to stay together despite the obviously unsatisfactory situation, namely “have we (let ourselves) become prisoners of our own selfishness?” She is seeking a response from her partner because she thinks that, even though there is clearly nothing meaningful left in their relationship, if they can both accept this reason for their problems, there is still a real chance they can at least be adult about why they no longer want each other and can then perhaps finally take the difficult, yet ultimately only sensible decision to go their separate ways.

Whilst I made the point in my attempted definition of Deep Soul that few recordings in the genre actually reflect genuine real-life situations, I seriously wonder if this recording isn’t one of the few exceptions. It was co-penned and co-produced by Beverly and the lyrics themselves are so ‘real’ and ‘adult’ that they could easily have been generated by actual personal experience. Her singing is intense whilst neither being dramatic nor all that far removed from the simple ‘spoken word’ (these being non-rhyming lyrics) and the accompaniment is sparse, comprising chiefly drum and muted brass with no vocal back-up whatsoever.

The performance on ![]() Have We Become Prisoners makes you feel you are eavesdropping on someone else’s heartache and creates a genuine ‘listening experience’, as the very best deep-soul sides tend to do. You don’t put this record on the turntable as a piece of music, you would only ever bother to do so to sit and really listen to what it has to say.

Have We Become Prisoners makes you feel you are eavesdropping on someone else’s heartache and creates a genuine ‘listening experience’, as the very best deep-soul sides tend to do. You don’t put this record on the turntable as a piece of music, you would only ever bother to do so to sit and really listen to what it has to say.

Johnny Copeland ![]() Dedicated To the Greatest (Wand 1114);

Dedicated To the Greatest (Wand 1114); ![]() Mother Nature (Wand unissued at the time);

Mother Nature (Wand unissued at the time); ![]() Love Attack Part 1 (Kent 4564) and

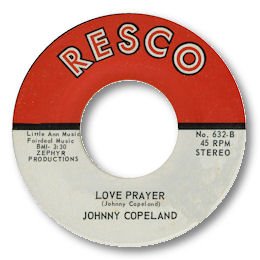

Love Attack Part 1 (Kent 4564) and ![]() Love Prayer (Resco 632)

Love Prayer (Resco 632)

Many singers who produced great deep-soul performances stemmed from the black churches but just a few had chiefly blues roots. Even so, some of these so-called bluesmen who could also sing ‘soul’ managed the transition quite fluently because they had long employed a soulful approach in their blues vocalising. In this respect, artists like Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland and Little Milton come readily to mind. Far less common, though, were out-and-out ballsy, gritty-voiced bluesmen who, come the time, could also create deep soulful emotion whilst still employing a powerful blues-based delivery. R&B and blues-steeped Harold Burrage showed it could be done in early 60s Chicago but it was left more to his protégé Johnny Sayles to cut some really powerful yet deep soul during those early years of the genre, though Sayles himself had no significant prior blues pedigree. However, at the other end of the country in far-flung Texas, Johnny ‘Clyde’ Copeland was another matter altogether.

Many singers who produced great deep-soul performances stemmed from the black churches but just a few had chiefly blues roots. Even so, some of these so-called bluesmen who could also sing ‘soul’ managed the transition quite fluently because they had long employed a soulful approach in their blues vocalising. In this respect, artists like Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland and Little Milton come readily to mind. Far less common, though, were out-and-out ballsy, gritty-voiced bluesmen who, come the time, could also create deep soulful emotion whilst still employing a powerful blues-based delivery. R&B and blues-steeped Harold Burrage showed it could be done in early 60s Chicago but it was left more to his protégé Johnny Sayles to cut some really powerful yet deep soul during those early years of the genre, though Sayles himself had no significant prior blues pedigree. However, at the other end of the country in far-flung Texas, Johnny ‘Clyde’ Copeland was another matter altogether.

Born on 27 March 1937 in Haynesville Louisiana, Copeland moved to Arkansas with his mother at 6 months of age but when he was 13 years old he moved again, this time to Houston, from where he ultimately developed a great reputation as a fine blues singer and guitarist, coming to be known as ‘The Texas Twister’. However, Copeland was a man who musically readily adapted to the styles of the day, his first record in 1958 having been an out-and-out rock ‘n roll offering for Mercury and his 60s work for Charles Booth’s Golden Eagle and Huey Meaux’s Crazy Cajun labels (much of the latter getting leased to Wand) often either fell fully into the ‘soul’ bag or, at least, showed strong 60’s/early 70’s soul ‘leanings’. Copeland would later revert to straight-ahead blues via a deal with Rounder Records and would cut the grammy-winning “Showdown” blues album for Alligator in 1985 with fellow bluesmen Albert Collins and Robert Cray. An inherited heart condition began to plague Copeland, though, and he had to endure open heart surgery on no less than eight occasions. He moved to Teaneck, New Jersey in 1990 but still regularly performed, cutting three more blues albums for Verve after 1992. From 1995 onwards he lived and performed with an internal ventricular ‘assist’ device, though eventually he succumbed to a complete heart transplant on the first day of 1997. Within 4 months he was back performing and after only 5 months made a memorable appearance at the WC Handy Awards in Memphis but, sadly, his new heart was ‘leaking’ and remedial surgery proved unsuccessful, Johnny finally passing on 3rd July 1997, aged only 60.

We feature four fine examples here of his gravelly ‘blues voice’ successfully melding with the deep soul sub-genre.

Sam Cooke musical tributes were quite common soon after the ex-Soul Stirrer’s untimely death in December 1964 but Copeland’s

Sam Cooke musical tributes were quite common soon after the ex-Soul Stirrer’s untimely death in December 1964 but Copeland’s ![]() Dedicated To The Greatest stands out as both a genuinely expressed and a genuinely soulful one. Clearly Johnny fully appreciated Sam’s great vocal qualities even though his own musical apprenticeship had been far removed from Cooke’s gospel-based one. The piece is a touch more ‘lilting’ than most truly deep offerings but both the subject-matter and Copeland’s expressive and heartfelt vocal give it that deep ‘feel’. After listing some of Sam’s hits, Johnny also asks Sam to say hello to other departed singers whom he clearly also rated, namely Jesse Belvin, Chuck Willis, Johnny Ace, Dinah Washington, Rudy Lewis and Nat Cole. The result could have been mawkish but isn’t. The side saw release twice in 1965 on Wand 1114 with two different ‘b’ sides and it featured on, and lent its name to, the fine UK Kent LP retrospective of Copeland’s more soulful output issued on Kent 067 in 1987 - but to my knowledge it’s not seen CD reissue beyond inclusion on the “Lost Soul Treasures Vol.3” possible bootleg (SOS-1004).

Dedicated To The Greatest stands out as both a genuinely expressed and a genuinely soulful one. Clearly Johnny fully appreciated Sam’s great vocal qualities even though his own musical apprenticeship had been far removed from Cooke’s gospel-based one. The piece is a touch more ‘lilting’ than most truly deep offerings but both the subject-matter and Copeland’s expressive and heartfelt vocal give it that deep ‘feel’. After listing some of Sam’s hits, Johnny also asks Sam to say hello to other departed singers whom he clearly also rated, namely Jesse Belvin, Chuck Willis, Johnny Ace, Dinah Washington, Rudy Lewis and Nat Cole. The result could have been mawkish but isn’t. The side saw release twice in 1965 on Wand 1114 with two different ‘b’ sides and it featured on, and lent its name to, the fine UK Kent LP retrospective of Copeland’s more soulful output issued on Kent 067 in 1987 - but to my knowledge it’s not seen CD reissue beyond inclusion on the “Lost Soul Treasures Vol.3” possible bootleg (SOS-1004).

Also recorded for Huey Meaux in Houston in 1965,

Also recorded for Huey Meaux in Houston in 1965, ![]() Mother Nature (intended for a never-issued Wand LP) is almost pure deep-gospel-soul, Johnny’s gruff but emotive vocals pleading and preaching like a church-quartet-leader in front of a sparse organ-and-piano-dominated musical backdrop. Terrific. The track first appeared on UK Kent’s various artist compilation LP “The Soul Of A Man” (Kent 038) in 1985, and then reappeared on the aforementioned UK Kent 067 Copeland retrospective LP; but I know of no CD reissue for it.

Mother Nature (intended for a never-issued Wand LP) is almost pure deep-gospel-soul, Johnny’s gruff but emotive vocals pleading and preaching like a church-quartet-leader in front of a sparse organ-and-piano-dominated musical backdrop. Terrific. The track first appeared on UK Kent’s various artist compilation LP “The Soul Of A Man” (Kent 038) in 1985, and then reappeared on the aforementioned UK Kent 067 Copeland retrospective LP; but I know of no CD reissue for it.

That Kent 067 LP also included Johnny’s very acceptable stop-go-tempo ‘take’ on a deep-soul treasure, namely James Carr’s great ![]() Love Attack. Recorded in 1971 it saw release on Kent 4564 the following year but also seems to have so far evaded the CD compilers. Few singers would have dared tackle such a sublime soul original but Copeland, whilst clearly not trying to copy Carr’s arrangement, still manages to retain the deep emotional pathos of the earlier Goldwax gem.

Love Attack. Recorded in 1971 it saw release on Kent 4564 the following year but also seems to have so far evaded the CD compilers. Few singers would have dared tackle such a sublime soul original but Copeland, whilst clearly not trying to copy Carr’s arrangement, still manages to retain the deep emotional pathos of the earlier Goldwax gem.

Our final Copeland soul offering,

Our final Copeland soul offering, ![]() Love Prayer, stems allegedly from 1974 and appeared originally on the presumably Texan-based Resco label (Resco 632). It saw LP reissue on “Down On Bended Knees” (RB 1002) and CD reissue only (to my knowledge) on the now rare Copeland “Soul Power” Japanese P-Vine PCB-2506 release from 1989. The song is virtually a reinterpretation of Al Green’s “God Blessed Our Love” as “Please Bless Our Love”, but the poignant storyline lyrics are quite different and Johnny’s involvement in them is intense and indicative of all that’s best in deep-soul. I rate this his finest-ever soul performance.

Love Prayer, stems allegedly from 1974 and appeared originally on the presumably Texan-based Resco label (Resco 632). It saw LP reissue on “Down On Bended Knees” (RB 1002) and CD reissue only (to my knowledge) on the now rare Copeland “Soul Power” Japanese P-Vine PCB-2506 release from 1989. The song is virtually a reinterpretation of Al Green’s “God Blessed Our Love” as “Please Bless Our Love”, but the poignant storyline lyrics are quite different and Johnny’s involvement in them is intense and indicative of all that’s best in deep-soul. I rate this his finest-ever soul performance.

Two other particularly fine Copeland soul-blues ballad performances to seek out are “Dear Mother” (Kent 4558 from 1971) and “Old Man Blues”, the flip of “Love Attack” on Kent 4564 from 1972. However both these fine sides appear on the 2003 UK Kent CDKEND 217 various-artists CD “Pounds Of Soul” which is no doubt already in the collections of many avid deep-soul enthusiasts and was partly compiled and fully notated by a certain Mr J Ridley.