Oscar Toney Jr

Oscar Toney Jr

by Pete Nickols

Sometimes even southern soul-men with truly impressive voices, who certainly recorded widely enough and even achieved enough national recognition to warrant inclusion in respected books on the subject, just simply fail to get a mention. Oscar Toney Jr. is a prime case in point – you can look for a reference to him in vain in ‘essential’ works like Peter Guralnick’s “Sweet Soul Music” and Gerri Hershey’s “Nowhere To Run” and you won’t even find an entry for him in Guinness’ “Who’s Who Of Soul Music”.

Barney Hoskyns at least gives him a little exposure in his books “Say It One Time For The Brokenhearted” and “From A Whisper To A Scream” and, of course, he does get a mention in Roben Jones’ book “Memphis Boys” about Chips Moman’s American Studios because Toney recorded much of his Bell material there – but we really have to thank soul specialists like John Abbey, Clive Richardson, Bill Dahl, Red Kelly and Heikki Suosalo for expounding in more depth about a soulman they all clearly – and rightly - highly regard(ed). I fully acknowledge how helpful their work has been in the construction of this article, although I did myself mount a full article on Oscar for my own “Vintage Soul” fanzine well before there were even any CD reissues of the singer’s material.

Oscar was born on 26th May 1939 in Selma, Alabama. However, at age 3, he moved to Columbus, Georgia, situated on the east bank of the Chattahoochee River which itself forms the boundary at this point between Georgia and Alabama. His father worked first as a presser in a local laundry and then as a cook at the nearby Fort Benning army base.

More importantly for Oscar’s musical credentials, he was introduced to gospel music at an early age as his father was a head deacon in the Gospel Tabernacle Church while his mother was a missionary worker there. From the age of 10, Oscar would go from church to church to sing ‘on the programs’. He favoured material by the Sensational Nightingales and the Soul Stirrers but his number-one gospel song was the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi’s “Our Father” (Peacock 1550), a superb Archie Brownlee-led performance which was one of the biggest gospel hits of the time, actually crossing over to the secular charts in 1950, making No.10 on both the Juke Box chart and the R&B one.

Toney Snr’s family was big and would ultimately comprise nine sons and three daughters, a further set of twins sadly dieing soon after their birth. In the late 50’s, three of Oscar’s sisters, Eula, Anne Lee and Mille, would sing with him for a short time as The Tonettes.

Toney Snr’s family was big and would ultimately comprise nine sons and three daughters, a further set of twins sadly dieing soon after their birth. In the late 50’s, three of Oscar’s sisters, Eula, Anne Lee and Mille, would sing with him for a short time as The Tonettes.

Meanwhile, whilst still in Junior High, Oscar was recruited to a spiritual group called the Sensational Melodies Of Joy, comprising fellow-students Herman Carter, Clarence Jenkins, Benny Madden and leader Lamar Douglas Cannon Jr. The group sang in local churches and auditoriums and continued to do so through Oscar’s time at Senior High, although he was by then also into secular music and won the talent show at the local Liberty Theater so often that they finally told him to let someone else have a chance. The rest of the group were also getting into secular music by then and duly re-formed as the Melodies, performing mainly pop and crossover hits rather than ‘hard’ R&B.

After graduation, Oscar worked in a pizzeria at the Fort Benning base (probably thanks to his father’s contacts there). However, when he was about 18 or 19 he joined with his two brothers Willie James and Roosevelt, his cousin James Walker and the unrelated Dallas Thomas to form The Valentines. This name was short-lived though and soon changed to The Searchers as a result of the boys regularly performing the Coasters’ “Searchin’” hit.

Via a local dee-jay, they soon got some limited exposure on a local radio and a TV station and this would lead to cutting a record – but first we have to sidetrack slightly.

A certain Donald ‘Cement’ McNally was heading south from his native Nebraska to open a club in Columbus when he heard about The Kayos Band in Thomaston, Georgia and offered them a job at his new venue. However their vocalist was lacklustre and, in seeking a replacement, they considered Oscar’s brother Willie James, who had been doing some ‘moonlighting’ with Bobby Moore’s Rhythm Aces, themselves then just a bunch of GIs at the Fort Benning army base. The Kayos’ bandleader, Sam Spark, knocked on Oscar’s door and asked if Willie James could sing with them for one night. However, Willie wasn’t around and Oscar duly volunteered himself. As he says, “that (one) night turned out to be eight years”.

A certain Donald ‘Cement’ McNally was heading south from his native Nebraska to open a club in Columbus when he heard about The Kayos Band in Thomaston, Georgia and offered them a job at his new venue. However their vocalist was lacklustre and, in seeking a replacement, they considered Oscar’s brother Willie James, who had been doing some ‘moonlighting’ with Bobby Moore’s Rhythm Aces, themselves then just a bunch of GIs at the Fort Benning army base. The Kayos’ bandleader, Sam Spark, knocked on Oscar’s door and asked if Willie James could sing with them for one night. However, Willie wasn’t around and Oscar duly volunteered himself. As he says, “that (one) night turned out to be eight years”.

Although now a ‘Kayo’, Oscar also remained with The Searchers who, in November 1960, cut a 45 for Cement McNally’s Mac label (#351) at a New Orleans radio station. The ballad side “Yvonne” was written by (and features thee-part harmony by) Oscar and his two brothers, while Walker and Thomas weren’t present. The backing is supplied by The Kayos. The flip was the more up-tempo “Little Wanda”.

Another Searchers Mac single, “Love” c/w “Oh Why Cha Cha Cha”, is rumoured to exist but Oscar recalls that, whilst he probably sang back-ups on it, it was really a Kayos recording put out by McNally under The Searchers’ name, with the Kayos other front-man Sonny Williams on lead vocals.

The Searchers had been around for about 4 years but now the other members decided not to make a career out of singing and Oscar was left to carry on both as a solo act and as a featured vocalist with the Kayos.

The Searchers had been around for about 4 years but now the other members decided not to make a career out of singing and Oscar was left to carry on both as a solo act and as a featured vocalist with the Kayos.

Solo-wise, around the time the Searchers 45 was recorded (and before 1960 was out) Oscar found himself cutting 4 solo sides for Macon-based Bobby Smith, to whom fellow singer Jimmy Soul had introduced him. These all-self-penned sides were leased out by Smith to King Records but only saw release much later, in 1964 and then in 1967 after Oscar’s Bell success (see later). The emotive pre-soul item ![]() Can It All Be Love was paired with the uptempo “You’re Gonna Need Me” on King 5906, while the mid-paced “I’ve Found A True Love” and uptempo “Keep On Loving Me” appeared together on King 6108, the latter track being covered by Oscar himself for Bell in 1967 as his first flip-side for that label, under the title “Ain’t That True Love” (see later). Two of Toney’s King sides can be found on “King’s Serious Soul, Vol.2” on the 2002 UK Kent CDKEND 206, while all four appeared on the bootleg 2-CD set “Selma’s Soul Son” (see later).

Can It All Be Love was paired with the uptempo “You’re Gonna Need Me” on King 5906, while the mid-paced “I’ve Found A True Love” and uptempo “Keep On Loving Me” appeared together on King 6108, the latter track being covered by Oscar himself for Bell in 1967 as his first flip-side for that label, under the title “Ain’t That True Love” (see later). Two of Toney’s King sides can be found on “King’s Serious Soul, Vol.2” on the 2002 UK Kent CDKEND 206, while all four appeared on the bootleg 2-CD set “Selma’s Soul Son” (see later).

The ‘still green’ Oscar had unknowingly signed a 10-year management contract with Smith but, due to a ‘falling out’, although still tied to the guy, Oscar never recorded for him again, resulting in a nearly seven-year period without any releases. Toney continued his work with the Kayos, mainly at Cement McNally’s C’est Bon Club in Columbus, where they were the ‘house band’. Eventually though, McNally grew tired of club-land and closed the C’est Bon, effectively bringing the Kayos’ ‘career’ to an end.

However, Oscar himself had already been ‘moonlighting’ at another, larger Columbus club, the Lavanna (which featured many top black acts and was where Jo Jo Benson first met a 17 year old Peggy Scott). Here, Toney had been filling in for two or three weeks with another group known as the Dothan Sextet. Their first lead singer had been Mighty Sam (McClain) but a certain Gerald Schroeder (self-styled as ‘Papa Don’) had whisked him away to Fame to cut some solo sides, something Don had then proceeded to do with his replacement in the Sextet, James Purify, only pairing him up vocally for the first time with his guitar-playing cousin Robert Dickey (to be known as Bobby Purify) after the pair had got to Fame.

However, Oscar himself had already been ‘moonlighting’ at another, larger Columbus club, the Lavanna (which featured many top black acts and was where Jo Jo Benson first met a 17 year old Peggy Scott). Here, Toney had been filling in for two or three weeks with another group known as the Dothan Sextet. Their first lead singer had been Mighty Sam (McClain) but a certain Gerald Schroeder (self-styled as ‘Papa Don’) had whisked him away to Fame to cut some solo sides, something Don had then proceeded to do with his replacement in the Sextet, James Purify, only pairing him up vocally for the first time with his guitar-playing cousin Robert Dickey (to be known as Bobby Purify) after the pair had got to Fame.

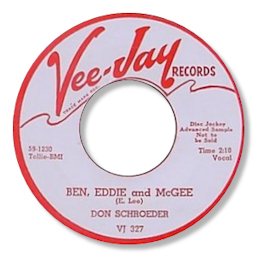

Schroeder, based in Pensacola, Florida, was a flamboyant but knowledgeable music-enthusiast, songwriter and one-time performer (he was the first white act to cut for Vee-Jay via 1959’s ‘rocka-ballad’ “Melanie” c/w the rockabilly “Ben, Eddie and McGhee” (#327) and went on to cut two more ‘teen’ 45s for Philips in 1962, namely ”Quicksand” c/w “My Kind Of Woman” (produced by Shelby Singleton on #40004) and his cover of Buddy Holly’s “Peggy Sue” c/w “Biggity Big” (#40067)).

He had been pitching songs in Nashville and, through 1962/3, had held down a midnight to 6am dee-jay shift on Radio WKDA in that city, where he had cut his final 'teen-market' 45 in 1963 for the then fledgling Sound Stage 7 label (before John R's involvement), namely "Papa I'm Sorry" c/w "Big And Lonely World" (SS7 2509). Soon Don returned to Pensacola to become a successful club-owner and local dee-jay there, on Radio WNVY, where he was known as “Papa Ding Dong Daddy Schroeder”. He then became the man who first took Birmingham, Alabama native, Barry Beckett to Fame, to back the Purifys, Barry having been a keyboard player at Papa Don’s Pensacola niterie.

It was the remaining members of the Dothan Sextet who suggested Oscar should go down with them to Pensacola, where they were due to play, so that he could sing with them and hopefully meet with Papa Don.

It was the remaining members of the Dothan Sextet who suggested Oscar should go down with them to Pensacola, where they were due to play, so that he could sing with them and hopefully meet with Papa Don.

Oscar says that when he did so, he didn’t know that Papa Don was in the audience, but adds that “when I came back off stage this tall white guy came in my dressing room and introduced himself. I wound up putting my name on the dotted line. At that time I was young, dumb and full of you-know-what. I just went along for the ride and what a hell of a ride it was!”

Papa Don remembers things differently. He says Toney came to his house. “This guy walks in, wearing a beautiful, full length, black, leather coat. Nice looking guy. And he says, ‘Papa Don? Mighty Sam sent me, and I’m Oscar Toney, Jr. And I want to cut a hit record for you.’ I said, ‘Man, I’m sorry, I just don’t have time to listen now. But if Mighty Sam sent you, I know you’re great. I will commit to try you out in a couple of weeks, and if I like it, we’ll cut a couple of sides on you. I’m going to be in the studio with the Purifys on such and such a date in Memphis. You meet me there'..."

Mighty Sam confirms he introduced Toney to Schroeder and speaks highly of Oscar. “I knew Oscar from Columbus…(He) was a good man, a very easy guy. Oscar didn’t fool around with any drugs or alcohol. He was always clean. He didn’t smoke, didn’t drink. Back in the old days we all did something, but Oscar didn’t do anything. A special kind of guy.”

So, at one point or another, Schroeder signed Oscar up, working out a deal with Bobby Smith to end Toney’s contact with the Macon man. Schroeder himself had a distribution arrangement with Larry Uttall’s New York label Bell; however, this was a one-record-at-a-time negotiable deal which had first come about after Don had recorded Mighty Sam’s “Sweet Dreams” at Fame. He’d then taken several promo copies to friends in Nashville and one of these, the publisher Buzz Cason, had told him he needed to get a copy to Larry Uttall, who just happened to be ‘in town’ at that time. The two met up at Uttall’s hotel and a ‘shake hands’ deal was struck, much to the chagrin of Atlantic’s Jerry Wexler who ended up trying to get hold of Sam’s song (and a deal with Schroeder) by upping the ante. However, Schroeder, though sorely tempted, felt he had to honour his arrangement with Utall and this he did. However, it wasn’t until much later (in June 1968) that Utall would sign a long-term exclusive production and publishing deal with Schroeder, a deal linked to the opening that month of Don’s own new, largely-Utall-financed Pensacola Studio (see later).

So, at one point or another, Schroeder signed Oscar up, working out a deal with Bobby Smith to end Toney’s contact with the Macon man. Schroeder himself had a distribution arrangement with Larry Uttall’s New York label Bell; however, this was a one-record-at-a-time negotiable deal which had first come about after Don had recorded Mighty Sam’s “Sweet Dreams” at Fame. He’d then taken several promo copies to friends in Nashville and one of these, the publisher Buzz Cason, had told him he needed to get a copy to Larry Uttall, who just happened to be ‘in town’ at that time. The two met up at Uttall’s hotel and a ‘shake hands’ deal was struck, much to the chagrin of Atlantic’s Jerry Wexler who ended up trying to get hold of Sam’s song (and a deal with Schroeder) by upping the ante. However, Schroeder, though sorely tempted, felt he had to honour his arrangement with Utall and this he did. However, it wasn’t until much later (in June 1968) that Utall would sign a long-term exclusive production and publishing deal with Schroeder, a deal linked to the opening that month of Don’s own new, largely-Utall-financed Pensacola Studio (see later).

Oscar’s first recording for Schroeder turned out to be a huge smash but Toney had no idea what was expected of him when, as requested, he turned up to meet Papa Don at Chips Moman’s American Studio in Memphis in mid-March 1967, a studio to which Schroeder had migrated from Fame, to where (as Don told Red Kelly) he did not return.

He was actually the first ‘outside’ producer to visit American and was there primarily to record “Shake A Tail Feather” with the Purifys. This turned into a mammoth session which taxed the musicians to the hilt, not helped by the fact that Paul Kelly from Muscle Shoals was putting in a new ‘board’ at the studio throughout the session itself, the Purify’s final master (obtained only after about 50 odd hours) being mixed on the new board while it was still upside down!

Poor Oscar was still sitting around, waiting to see if Don was going to give him an audition or let him cut a demo, when the session-weary house band started packing up. Oscar intervened with Schroeder who was sitting back with Chips Moman and who had genuinely forgotten all about him. Don told Oscar to go out on the studio floor, up to the microphone and “sing the greatest old song you know – the song that best illustrates your talent and tells who Oscar Toney Jr. is.”

Poor Oscar was still sitting around, waiting to see if Don was going to give him an audition or let him cut a demo, when the session-weary house band started packing up. Oscar intervened with Schroeder who was sitting back with Chips Moman and who had genuinely forgotten all about him. Don told Oscar to go out on the studio floor, up to the microphone and “sing the greatest old song you know – the song that best illustrates your talent and tells who Oscar Toney Jr. is.”

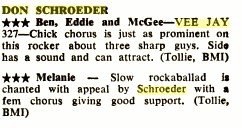

Oscar duly obliged, Moman rolled the tape and the singer began a recitation (rap), something he had regularly done at his club performances prior to easing into songs like “That’s How Strong My Love Is”, “You’re Gonna Make Me Cry” and “I Stand Accused”. However, on this particular occasion he chose Jerry Butler & The Impressions’ big 1958 hit ![]() For Your Precious Love and, as Oscar says, “that’s when they jumped at it”.

For Your Precious Love and, as Oscar says, “that’s when they jumped at it”.

It’s true that Jerry Butler’s beautiful pre-soul gospel-meets-doo-wop song became one of the most ‘covered’ songs in soul music, the superb singer Garnet Mimms having had a No.26 R&B hit with it on U-A 658 more than three years before Toney cut his version. However, Toney’s recording, which was cut in a mere 15 minutes, takes some beating! The 1 min. 30 second sermon-like rap intro is itself soul personified as Moman’s superb Memphis Boys tinkle away subtly behind Oscar’s preaching, before later New York overdubbed female back-up vocals by Melba Moore, Doris Troy and Ellie Greenwich - and then strings - cut in too. But when Oscar opens up and starts to actually sing the song, the glorious unrestrained gospel-honed soul-power of the man’s magnificent voice is fully realised. With such a long ‘intro’ there is actually only 1 min. 46 secs of ‘singing’ but the performance just drips with emotion and, despite its inherent ‘blackness’, Larry Uttal’s promotion men managed to help the record on Bell 672 to achieve not only a No.4 R&B spot but a very creditable No.23 crossover Pop position too.

It’s true that Jerry Butler’s beautiful pre-soul gospel-meets-doo-wop song became one of the most ‘covered’ songs in soul music, the superb singer Garnet Mimms having had a No.26 R&B hit with it on U-A 658 more than three years before Toney cut his version. However, Toney’s recording, which was cut in a mere 15 minutes, takes some beating! The 1 min. 30 second sermon-like rap intro is itself soul personified as Moman’s superb Memphis Boys tinkle away subtly behind Oscar’s preaching, before later New York overdubbed female back-up vocals by Melba Moore, Doris Troy and Ellie Greenwich - and then strings - cut in too. But when Oscar opens up and starts to actually sing the song, the glorious unrestrained gospel-honed soul-power of the man’s magnificent voice is fully realised. With such a long ‘intro’ there is actually only 1 min. 46 secs of ‘singing’ but the performance just drips with emotion and, despite its inherent ‘blackness’, Larry Uttal’s promotion men managed to help the record on Bell 672 to achieve not only a No.4 R&B spot but a very creditable No.23 crossover Pop position too.

Of course a flip-side also had to be cut and it seems likely that the short, 1 minute 45 second “Ain’t That True Love” was also cut that day in something of a hurry. As noted above, this was a re-cut (with a name change to please Schroeder) of Oscar’s old self-penned King side “Keep On Loving Me”. This bouncy opus with its Beatles-like guitar riff is decidedly ‘crossover’ in style but showcases some great playing by the Memphis Boys and is still extremely well sung by Toney who gives it his all, from his opening scream onwards!

The label of the released Toney 45 gives Chips Moman and George Schowerer engineering credit, George being the regular engineer at Mira Sound, New York, who helped Don with the later string and background vocal overdubs/remixes.

The label of the released Toney 45 gives Chips Moman and George Schowerer engineering credit, George being the regular engineer at Mira Sound, New York, who helped Don with the later string and background vocal overdubs/remixes.

It’s also nice that production credits are awarded not just to Papa Don but also to the Memphis Boys by name. Papa Don said he wanted them to have credit for the long combined Purifys-then-Toney session and also a ‘piece’ of the records, Schroeder claiming he paid them $200 each after the 45s became hits – although the Memphis Boys don’t seem to recall this.

Of course, Utall now urgently wanted Schroeder to produce an album on Toney to issue on the back of the hit, as well as a follow-up single, to be drawn from it.

This next session was quickly arranged and the Memphis musicians welcomed Oscar back, Reggie Young noting “I liked that album – I liked him. What you heard was what you got. He didn’t try to be anything other than himself.”

The album became one of the great southern soul ‘sets’. Schroeder and Schowerer’s ‘sweetening’ work was tastefully done and despite the LP being aimed at the crossover market as well as the R&B one, the sheer top-quality of both Toney’s vocals and the Memphis Boys’ playing elevates it to something of real soul significance. Otis Redding did a (probably solicited) letter of commendation for insertion on the back sleeve and Papa Don was so impressed with the musicians that he insisted on photos of them appearing there too. Toney is also featured but, as with so many albums by black artists of the time for which producers also wanted ‘white’ radio-play and sales, Oscar does not appear on the front cover, being replaced by several small shots of a very ‘sixties’ Caucasian couple!

Three wonderful large-size photos of this session appear on Red Kelly’s fine blog (one of which is also on the cover of Roben Jones’ “Memphis Boys” book) but they are the property of Papa Don and it would be improper to feature them here – so I do suggest you visit his website here and then right-click on each photo, next selecting ‘open in a new window’. That way you can best enjoy these wonderful pieces of soul history.

According to Oscar, the nine new songs were finally sorted in the studio between 6pm one evening and about 8am the next morning, with the whole album only taking three days to complete. Although 9 of the album’s 11 tracks were ‘covers’ (the originals being Oscar’s “Ain’t That True Love” and Darryl Carter’s “No Sad Songs”), as Heikki Suosalo succinctly notes: “There’s no way you can call them copies. They are highly imaginative, dramatically arranged and richly orchestrated unique gems delivered with an overflow of passion and true soul.”

We should perhaps enlarge on the assertion that “No Sad Songs” was not a cover but a Toney original. Darryl Carter came to Memphis from his native Chicago in 1965 and soon linked up with Chips Moman. By ’67 he was a regular around the American Studio, writing songs and looking for Moman to place them. Toney himself says “one of the guys (obviously Carter) actually wrote that on the spot and I did it first”.

We should perhaps enlarge on the assertion that “No Sad Songs” was not a cover but a Toney original. Darryl Carter came to Memphis from his native Chicago in 1965 and soon linked up with Chips Moman. By ’67 he was a regular around the American Studio, writing songs and looking for Moman to place them. Toney himself says “one of the guys (obviously Carter) actually wrote that on the spot and I did it first”.

While Joe Simon cut it and had a hit with it as early as January 1968 on Sound Stage 7 2602 (and even named a 1968 album after it on Sound Stage 7 15004), that seems to have clearly been a later version than Toney’s as Oscar’s LP containing his recording had entered the Pop album chart much earlier on 29th July 1967. It would seem that this album was cut at a session around late June-early July 1967, just as Oscar’s first Bell single moved up from No.7 to No.4 in the R&B chart and from No.26 to No.23 in the Pop Top 100. Meanwhile, although Red Kelly suggests Mark Lindsey was the first to cut the song as vocalist on the American Studio-recorded Paul Revere & The Raiders LP “Goin’ To Memphis” (Columbia 9605), this album didn’t chart till March 1968 and Roben James’ chronology has the group not turning up at American for the session until early 1968. Therefore I think there is little doubt that Oscar’s “No Sad Songs” is the original version, followed by Joe Simon’s and then the Raiders/Lindsey’s.

From the album, Oscar’s next 45 pairing was duly drawn, namely his powerful reading of Bobby Bland’s great ![]() Turn On Your Lovelight and his slightly less impressive interpretation of Chuck Jackson’s “Any Day Now” (Bell 681), the ‘A’ side making No.37 R&B/No.65 Pop in the fall of’67. Of the other non-single tracks on the LP, my own favourite may surprise some but it’s Oscar’s simple but oh-so-soulful interpretation of the old Jaye P. Morgan pop hit

Turn On Your Lovelight and his slightly less impressive interpretation of Chuck Jackson’s “Any Day Now” (Bell 681), the ‘A’ side making No.37 R&B/No.65 Pop in the fall of’67. Of the other non-single tracks on the LP, my own favourite may surprise some but it’s Oscar’s simple but oh-so-soulful interpretation of the old Jaye P. Morgan pop hit ![]() That’s All I Want From You. In addition to Oscar’s lovely wistful vocal, it is in fact that very organ-backed simplicity and spare quality which really appeals to me, along with the pathos-drenched string overdubs. The piece just cocoons me in its simple beauty. However, if it’s not for you, you’re in good company – Toney himself told Bill Dahl: “I had never heard that song (before) and…I hated it. I thought it was too rich for me.”

That’s All I Want From You. In addition to Oscar’s lovely wistful vocal, it is in fact that very organ-backed simplicity and spare quality which really appeals to me, along with the pathos-drenched string overdubs. The piece just cocoons me in its simple beauty. However, if it’s not for you, you’re in good company – Toney himself told Bill Dahl: “I had never heard that song (before) and…I hated it. I thought it was too rich for me.”

“Moon River” on the other hand comes across just a tad too over-arranged and schmaltzy for my own taste, while Oscar’s take on Jerry Butler’s “He Will Break Your Heart” is much better. His “Dark End Of The Street” is good too in its own dramatic and fairly fully-orchestrated way because it never tries to emulate what is a peerless pared-down, sombre original by James Carr. Exactly the same comment applies to Oscar’s version of Penn and Moman’s “Do Right Woman – Do Right Man”. More uptempo and quite a strong offering is the aforementioned original of “No Sad Songs” while Oscar also makes a really good job of Hinton and Greene’s mid-paced “Down In Texas”, cut originally by Don Varner a few months earlier on 19 February 1967 at Quinvy, Toney’s version seeing later ‘in the can’ 45 release on Bell 776 in 1968, paired with a reissue of “Ain’t That True Love”. This single only emerged after Oscar had ceased working for Papa Don (see later).

“Moon River” on the other hand comes across just a tad too over-arranged and schmaltzy for my own taste, while Oscar’s take on Jerry Butler’s “He Will Break Your Heart” is much better. His “Dark End Of The Street” is good too in its own dramatic and fairly fully-orchestrated way because it never tries to emulate what is a peerless pared-down, sombre original by James Carr. Exactly the same comment applies to Oscar’s version of Penn and Moman’s “Do Right Woman – Do Right Man”. More uptempo and quite a strong offering is the aforementioned original of “No Sad Songs” while Oscar also makes a really good job of Hinton and Greene’s mid-paced “Down In Texas”, cut originally by Don Varner a few months earlier on 19 February 1967 at Quinvy, Toney’s version seeing later ‘in the can’ 45 release on Bell 776 in 1968, paired with a reissue of “Ain’t That True Love”. This single only emerged after Oscar had ceased working for Papa Don (see later).

While Papa Don moans about the high cost of making LPs on the back of single hits and the usually relatively poor sales of such releases, he couldn’t really complain about Oscar’s effort because it did make No.27 on the National R&B Album chart and it also crossed over to spend no less than 5 weeks in the lower reaches of the Top 200 Pop LP chart, no mean feat in those days for a still little-known, one-hit, black artist.

However, despite the obvious empathy between Oscar and the fine Memphis Boys at American, Schroeder soon fell out with Chips Moman and no further Toney sides were cut there.

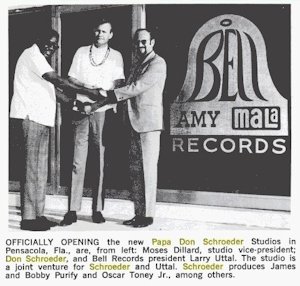

There has been much speculation as to where the remainder of Toney’s post-American Studios Bell recordings were made. You will have noted above that Papa Don says he did not return to Fame and, to my ears, none of the ensuing 45s (not even “Unlucky Guy”) have that 1967-8 Fame sound belonging to Messrs Johnson, Beckett, Hawkins and co. However, as noted earlier, Schroeder’s own new Pensacola studio (financed chiefly by Larry Utall) did not open until June 1968, too late for Toney’s next three singles to have been cut there, although the fourth (and final ‘new’ Bell single) was. Certainly, even in 1967, Schroeder was already lining up ex-Greenville NC native Moses Dillard and his musicians as ‘his’ band, with Dillard later to become Vice-President of Papa Don’s own studio, where his musicians would become the ‘house band’. And so it was that Oscar’s first post-American 45 was arranged by Dillard, as the label makes plain. We just don’t know where this single and the next two were cut but Nashville has to feature high on the ‘possibles list’ as Schroeder already had many contacts there, especially Buzz Cason, who would later get involved in the Bell-sponsored group of Studios that would include Papa Don’s own. It seems these next Toney recordings either featured musicians taken to the studio in question by Schroeder and/or Dillard or else the in-house musicians who were already in situ.

There has been much speculation as to where the remainder of Toney’s post-American Studios Bell recordings were made. You will have noted above that Papa Don says he did not return to Fame and, to my ears, none of the ensuing 45s (not even “Unlucky Guy”) have that 1967-8 Fame sound belonging to Messrs Johnson, Beckett, Hawkins and co. However, as noted earlier, Schroeder’s own new Pensacola studio (financed chiefly by Larry Utall) did not open until June 1968, too late for Toney’s next three singles to have been cut there, although the fourth (and final ‘new’ Bell single) was. Certainly, even in 1967, Schroeder was already lining up ex-Greenville NC native Moses Dillard and his musicians as ‘his’ band, with Dillard later to become Vice-President of Papa Don’s own studio, where his musicians would become the ‘house band’. And so it was that Oscar’s first post-American 45 was arranged by Dillard, as the label makes plain. We just don’t know where this single and the next two were cut but Nashville has to feature high on the ‘possibles list’ as Schroeder already had many contacts there, especially Buzz Cason, who would later get involved in the Bell-sponsored group of Studios that would include Papa Don’s own. It seems these next Toney recordings either featured musicians taken to the studio in question by Schroeder and/or Dillard or else the in-house musicians who were already in situ.

So, Oscar’s next, Dillard-arranged 45 (Bell 688) sees the ‘A’ side showcasing some furious high-pitched Toney vocals on Charles Chalmers’ driving up-tempo song “You Can Lead Your Woman To the Altar”, originally a William Bollinger vehicle cut at Fame in January that year and leased to Chess (#1994). Toney’s re-make spent the latter half of October ’67 ‘bubbling under’ the Billboard Pop chart, peaking at No. 120 but actually made No.86 on the Cashbox Pop listings. On the flip-side of this 45, however, we get to enjoy some truly great deep-soul-singing from our man on Dillard’s co-penned Unlucky Guy, which suffers merely a tad from some unnecessarily strident-sounding horn work.

Released at the very beginning of 1968 on Bell 699, “Without Love (There Is Nothing)”, a re-make of Clyde McPhatter’s 1957 hit on Atlantic 1117, made No.47 R&B and crept into the 90’s in both the Billboard and the Cashbox Pop charts. After an opening monologue, the song becomes so dramatic and has so much over-orchestration that it almost becomes bombastic; however Oscar’s self-penned deepie,

Released at the very beginning of 1968 on Bell 699, “Without Love (There Is Nothing)”, a re-make of Clyde McPhatter’s 1957 hit on Atlantic 1117, made No.47 R&B and crept into the 90’s in both the Billboard and the Cashbox Pop charts. After an opening monologue, the song becomes so dramatic and has so much over-orchestration that it almost becomes bombastic; however Oscar’s self-penned deepie, ![]() A Love That Never Grows Cold, on the flip, was something else! A magnificently-sung crie de coeur, it ranks as one of Oscar’s finest moments.

A Love That Never Grows Cold, on the flip, was something else! A magnificently-sung crie de coeur, it ranks as one of Oscar’s finest moments.

Strangely, Schroeder would re-issue this fine track as the flip of Oscar’s next single too and, in between, he would produce and release an arguably even deeper version on Bell 708 by the unknown Jimmy and Louise Tig & Co., with a wonderful, mournful-yet-haunting solo vocal by Louise.

The ‘A’ side of Oscar’s Bell 714 release was a truly stunning cover of Eddie Floyd’s lovely 1964 Safice 334 song ![]() Never Get Enough Of Your Love. Again a monologue kicks it off, in front of the strings, but this is top-drawer deep country soul, reminiscent at times of Tony Borders’ “Cheaters Never Win”. Oscar wails wonderfully towards the song’s climax, backed by some great female voices. Just a terrific soul recording, which amazingly never made it to the R&B charts at all, creeping into the Pop charts in late April 1968 for just 2 weeks and only making No.95.

Never Get Enough Of Your Love. Again a monologue kicks it off, in front of the strings, but this is top-drawer deep country soul, reminiscent at times of Tony Borders’ “Cheaters Never Win”. Oscar wails wonderfully towards the song’s climax, backed by some great female voices. Just a terrific soul recording, which amazingly never made it to the R&B charts at all, creeping into the Pop charts in late April 1968 for just 2 weeks and only making No.95.

The ‘A’ side of Oscar’s last ‘new’ Bell 45, “Until We Meet Again”, was self-penned in a hotel room between gigs in the UK. It’s a slightly jaunty but very appealing piece of country-soul, one of the first sides recorded circa late-June 1968 at Papa Don’s brand new studio and under his now formalised production and publishing deal with Larry Utall.

Some Wayne Jackson-arranged horns introduce the mid-paced, ultimately big-building flip, a cover of Jerry Butler’s late-1965 hit on Vee-Jay 707, “Just For You”.

Toney wasn't happy with the Pensacola results though, saying "Papa Don could never come up with the right sound... Chips had professional musicians and he could engineer that board. He could get that mix. Papa Don was trying to do that for himself but he just couldn't."

Adding to the widening gulf between the two men was Oscar’s view that he just wasn't getting the appreciation he deserved. According to Papa Don, Oscar quit simply because he didn’t like being on the road all the time. But Oscar says: "I'd had about as much as I could stand, him disrespecting his artists... the only way I knew to hurt him was through the pocket. I had to sacrifice myself to hurt him."

After the split, Bell would release one more Toney single 'out of the can' (“Down In Texas” from the album would be linked with “Ain’t That True Love” on Bell 776) but no Oscar Toney 45 would ever chart again.

It would be 1988 before the first LP compilation of Oscar’s Bell sides appeared on the very aptly-named “Papa Don’s Preacher” (UK Charly CRB 1183). The best CD compilation of Toney’s Bell output is on 2001’s “For Your Precious Love” (Sundazed SC 11093) which also includes an alternate take of “You Can Lead Your Woman To the Altar” and a very good, previously unissued demo-cover of Chuck Jackson’s “Gettin’ Ready For The Heartbreak”. However Toney’s “For Your Precious Love” hit is faded rather early on this CD and a fuller version is on the earlier 1998 “Oscar’s Winners” Bell-period compilation on UK Westside WESA 832. A virtual reissue of the Sundazed CD appeared in 2006 under the same title on Rev-ola CR REV 155, except that this excluded the alternate take and the unissued track.

Phil Walden knew of Oscar through Otis Redding and his Macon-based ex-road manager Earl ‘Speedo’ Simms and had visited him in ’67 at his Columbus home to see about possibly managing him, although, by then, Toney had already signed with Papa Don. However, when Oscar (now a free agent) heard in 1970 that Phil had started up his own Capricorn label (initially distributed by Atlantic) he was very interested and duly re-contacted Phil. A deal was soon concluded and Oscar became one of the first performers to record for the Macon-based label.

Phil Walden knew of Oscar through Otis Redding and his Macon-based ex-road manager Earl ‘Speedo’ Simms and had visited him in ’67 at his Columbus home to see about possibly managing him, although, by then, Toney had already signed with Papa Don. However, when Oscar (now a free agent) heard in 1970 that Phil had started up his own Capricorn label (initially distributed by Atlantic) he was very interested and duly re-contacted Phil. A deal was soon concluded and Oscar became one of the first performers to record for the Macon-based label.

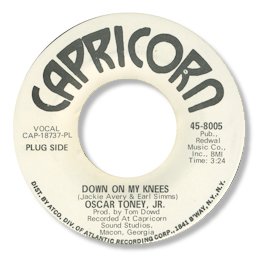

He would cut four 45s for Capricorn, his first in 1970 being a Tom Dowd produced and engineered Jackie Avery and Earl Simms’ super-deep winner called ![]() Down On My Knees, the fifth Capricorn single release on #8005.

Down On My Knees, the fifth Capricorn single release on #8005.

The flip was the lighter-weight uptempo pop-soul of another Avery tune, “Seven Days Tomorrow”. A follow-up on Capricorn 8010 was the label’s last release in 1970 and paired another bouncy item, “Person To Person”, with the monologue-introduced, compelling deep-soul of Avery and Toney’s ![]() I Wouldn’t Be A Poor Boy.

I Wouldn’t Be A Poor Boy.

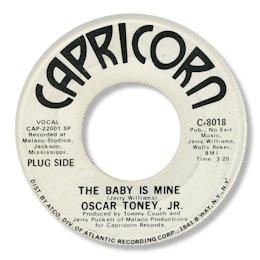

In early 1971, Swamp Dogg turned up at Malaco to produce Toney on his next Dogg-penned track, ![]() The Baby Is Mine, a very good, involving slab of post-divorce storyline soul, later also covered by Joe Tex on his 1972 album “From The Roots Came The Rapper” (Atlantic 8292). The flip was a fine message-soul cover of Ike & Tina Turner’s then recent Ike Turner-penned “Workin’ Together” release (a No.41 R&B hit at the end of 1970 on Liberty 56207 which spawned a 1971 album of that name on Liberty 7650). There’s no doubt that Oscar’s great voice was still on top form for these superb Capricorn sides but they weren’t selling ‘big’ and whether this was due to a lack of promotion or because they were too ‘southern’ or too ‘black’ is hard to know.

The Baby Is Mine, a very good, involving slab of post-divorce storyline soul, later also covered by Joe Tex on his 1972 album “From The Roots Came The Rapper” (Atlantic 8292). The flip was a fine message-soul cover of Ike & Tina Turner’s then recent Ike Turner-penned “Workin’ Together” release (a No.41 R&B hit at the end of 1970 on Liberty 56207 which spawned a 1971 album of that name on Liberty 7650). There’s no doubt that Oscar’s great voice was still on top form for these superb Capricorn sides but they weren’t selling ‘big’ and whether this was due to a lack of promotion or because they were too ‘southern’ or too ‘black’ is hard to know.

Toney’s final Capricorn 45 appeared in 1972 on #0005 and once again Jerry Williams was around to co-write, arrange and produce it. It was engineered by David Johnson and so might well have been cut at Quinvy Studios in Sheffield. “Thank You, Honey Chile” was a dramatically-sung acknowledgement by Oscar (in a rather higher register than usual) of all his girl had done for him, while the somewhat lower-profile flip, “I Do What You Wish (But I Wish What You Do Wouldn't Hurt Me So)”, just happens to be a song which Oscar himself enjoys.

Toney’s final Capricorn 45 appeared in 1972 on #0005 and once again Jerry Williams was around to co-write, arrange and produce it. It was engineered by David Johnson and so might well have been cut at Quinvy Studios in Sheffield. “Thank You, Honey Chile” was a dramatically-sung acknowledgement by Oscar (in a rather higher register than usual) of all his girl had done for him, while the somewhat lower-profile flip, “I Do What You Wish (But I Wish What You Do Wouldn't Hurt Me So)”, just happens to be a song which Oscar himself enjoys.

Capricorn’s increasing concentration on southern rock music caused Oscar to part company with the label in ’72. Sadly, no authorised reissues of his wonderful work there have yet appeared. In the 1990’s, Soul From The Vaults issued a 12-inch mini-LP (SFTV 1024) featuring 6 of these tracks, with some unrelated tracks by the then also little re-issued Billy Young on the other side. SFTV are the company who currently issue the “Deep Dip…” series of CDs, some of which are reviewed on this web-site.

It’s doubtful that this release was ‘authorised’ – nor was the aforementioned 2-CD ‘boot’ called “Selma’s Soul Son”, which, at the beginning of Disc 2, featured 7 of the 8 Capricorn outings, only omitting “I Do What You Wish (But I Wish What You Do Wouldn't Hurt Me So)”.

Papa Don made further contact with Oscar after he’d left Capricorn in 1972 and took him down to Nashville to cut “Share Your Love With Me” and a cover of Percy Sledge’s “When A Man Loves A Woman”, but Oscar’s heart wasn’t really in it and Schroeder failed to get anything worth releasing.

Throughout the late 60’s and early 70’s, Oscar certainly toured internationally on the back of his popularity in Germany, South Africa (where he did a six-week tour with Arthur Conley, Peaches & Herb and Inez Foxx) and Britain, which he reckons he visited 15 times.

Indeed, it was on a British tour in 1973 that Oscar’s luck was ‘in’ when he encountered (again) “Blues & Soul” editor, record-shop proprietor and owner of UK Contempo Records, John Abbey. Abbey had done two articles on Toney for his magazine back in February and October 1971 and, in ’73, Abbey caught some of his UK shows and managed to persuade Oscar to strike a deal with Contempo, the label’s first release only having been issued as recently as 5th January that year.

Indeed, it was on a British tour in 1973 that Oscar’s luck was ‘in’ when he encountered (again) “Blues & Soul” editor, record-shop proprietor and owner of UK Contempo Records, John Abbey. Abbey had done two articles on Toney for his magazine back in February and October 1971 and, in ’73, Abbey caught some of his UK shows and managed to persuade Oscar to strike a deal with Contempo, the label’s first release only having been issued as recently as 5th January that year.

The original ‘A’ side on Oscar’s first Contempo outing (#C6) was David Gates’ “Everything I Own”, a fine example of Toney’s successful souling-up of a well-written, sensitive pop song about a son wishing he had said more to his now deceased father while he was still alive. The flip-side took Oscar back yet again to Jerry Butler, this time for a fine re-make of the Ice Man’s ![]() Kentucky Bluebird (A Message To Martha). Both are very good, emotive, dramatic soul workouts with Oscar in great voice.

Kentucky Bluebird (A Message To Martha). Both are very good, emotive, dramatic soul workouts with Oscar in great voice.

As with Oscar’s upcoming LP, Abbey would closely oversee proceedings but the arrangements and much of the keyboard work were done by Gerry Shury, a Brixton, London caucasian and an ex-session pianist for late-60’s UK producer Tony McCauley. Strangely, the appealing ‘heavenly choir’ on both sides of Oscar’s first 45 was removed from both tracks when they were later included on Toney’s 1974 Contempo LP.

Next, however, a lateish-1973 Contempo 45 appeared on #24, featuring the self-penned “Everybody’s Needed”, a soulful enough but very pedestrian slow-waltz-paced piece and also Toney’s take on Cincinnati-born guitarist-singer Chuck Brooks’ atmospheric, slow-but-funky 1970 Volt 4034 forty-five, “Love’s Gonna Tear Your Playhouse Down”.

Next, however, a lateish-1973 Contempo 45 appeared on #24, featuring the self-penned “Everybody’s Needed”, a soulful enough but very pedestrian slow-waltz-paced piece and also Toney’s take on Cincinnati-born guitarist-singer Chuck Brooks’ atmospheric, slow-but-funky 1970 Volt 4034 forty-five, “Love’s Gonna Tear Your Playhouse Down”.

In early 1974, Oscar’s next Contempo single appeared on CS 2002, coupling a rather funky version of the old Syl Johnson 1969 Twinight 125 hit “Is It Because I’m Black” with yet another Jerry Butler original from 1962 on Vee-Jay 451, “Make It Easy On Yourself”, which Oscar sang in a relaxed, almost supper-club fashion, complete with monologues at both ends of the piece. This performance was issued in the States as a two-part 45 on Contempo 6602. Indeed there was clearly an attempt by John Abbey around this time to establish Contempo in the States, a US office being opened at the beginning of May ’74 at 300 W.55th St., New York. In addition to the “Make It Easy…” US 45, US Contempo also put out Oscar’s “Is It Because I’m Black” c/w ”The Thrill is Gone” on #7702 and then Abbey even managed to obtain a release on Atco 6933 of “Everybody’s Needed”, coupled this time with “Everything I Own”, taken from Oscar’s first UK Contempo 45.

Back in the UK, Oscar’s next Contempo single featured his rather warm, easy-going take on The Tempts’ and Otis’ “My Girl”, coupled with a bluesier item in the shape of the old 1951 Roy Hawkins Modern 826 hit, better-known today via B.B. King’s 1969 version, “The Thrill Is Gone”.

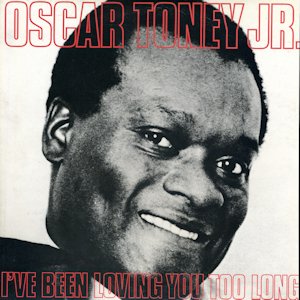

John Abbey also had in the can a version by Oscar of Otis’ “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long” (yet another Jerry Butler co-penned song) as well as a newly re-cut interpretation of his first big ex-Butler hit “For Your Precious Love”. Before these appeared together on a late-1974 Contempo 45 (#2043), they were used, along with seven other already-issued sides, to make up Oscar’s lone 9-track Contempo LP, named after the above Otis song and released on Contempo CLP 511. The title-track was a real tour de force by Toney, an impressive performance which utilised most aspects of his vocal flexibility and wide range. The re-cut of “For Your Precious Love” is longer than the original and therefore, even allowing for the monologue, contains more actual singing, which is of a really dynamic and dramatic quality, especially towards the track-end. For me, this performance actually succeeds in rivalling Toney’s earlier hit version.

John Abbey also had in the can a version by Oscar of Otis’ “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long” (yet another Jerry Butler co-penned song) as well as a newly re-cut interpretation of his first big ex-Butler hit “For Your Precious Love”. Before these appeared together on a late-1974 Contempo 45 (#2043), they were used, along with seven other already-issued sides, to make up Oscar’s lone 9-track Contempo LP, named after the above Otis song and released on Contempo CLP 511. The title-track was a real tour de force by Toney, an impressive performance which utilised most aspects of his vocal flexibility and wide range. The re-cut of “For Your Precious Love” is longer than the original and therefore, even allowing for the monologue, contains more actual singing, which is of a really dynamic and dramatic quality, especially towards the track-end. For me, this performance actually succeeds in rivalling Toney’s earlier hit version.

Although, aesthetically, there were many high-points to the album, it was not a big UK seller and did not see release in the USA. Its quality, though, was appreciated by soul fans everywhere and Japanese demand would later create a reissue of it on Vivid Sound 1504 in 1980.

A final Oscar Contempo 45 appeared in 1975 on #2075. This featured a very funky version of Bobby Rush’s 1971 song “Chicken Heads”, coupled with a reissue of “Everybody’s Needed”.

A final Oscar Contempo 45 appeared in 1975 on #2075. This featured a very funky version of Bobby Rush’s 1971 song “Chicken Heads”, coupled with a reissue of “Everybody’s Needed”.

The nine tracks on the Contempo album, plus “Chicken Heads” and the ‘choir-included’ 45 versions of “Kentucky Bluebird (Message To Martha)” and “Everything I Own” finally appeared in CD format in 2007 on “Loving You Too Long” (UK Shout 40). Oscar also reckons there’s an unissued Contempo-cut version of “Unchained Melody” somewhere around but that hasn’t surfaced yet.

Oscar appreciated that Contempo had tried to keep his recording career going but lack of decent exposure Stateside meant he parted ways with John Abbey in 1975 and returned to Columbus to pick up again on the local club scene. However, in 1978 he moved north to Fitchburg, Massachusetts, where he got employment as a security guard at a General Electric plant before soon working actually within the plant itself. Then, in the early 80’s, he moved again, this time to Cedar Rapids in Iowa to labour for the National Oats company. However, the company eventually had to cut back on staff and began offering early retirement, which Oscar took, chiefly because he and his wife Carolyn were by then tiring of the cold Iowa climate.

They moved back south in 1997 to an apartment in Opelika, Alabama and soon, via a contact in Atlanta, Oscar got to meet up again with John Abbey who was then resident in that city and running Ichiban Records. Oscar cut a couple of demos for John but nothing came of it, although Oscar was prompted to return to the music biz and appeared at the Porretta Terme Soul Festival in Italy for the first time in July 1999.

They moved back south in 1997 to an apartment in Opelika, Alabama and soon, via a contact in Atlanta, Oscar got to meet up again with John Abbey who was then resident in that city and running Ichiban Records. Oscar cut a couple of demos for John but nothing came of it, although Oscar was prompted to return to the music biz and appeared at the Porretta Terme Soul Festival in Italy for the first time in July 1999.

Later Oscar cut two new songs which were included on a privately-produced 9-track CD (and cassette) entitled “Resurfaces Year 2000” (OTJR – no number). The seven other tracks were 6 existing Contempo recordings and one Bell one (“Down In Texas”). The new tracks were the storyline soul of “I’m Not The Dad” and the lighter-weight item “You Can’t Come In”.

In 2000, he finally cut his first completely new set for many years, for Bob Grady Records, namely the CD “Guilty Of Loving You” (BGR 9518), which would also see later UK release in 2006 on Shout 30, repackaged and re-named as “Guilty, Southern Soul Renaissance”. Oscar was still in good form as shown especially on the three songs penned for the 10-track set by Dave Williams and Mick Parker, including the fine title-track. However, the ‘standout’ for me was Oscar’s self-penned ![]() I’m Sorry which proved that even genuine deep soul could survive into the new millennium. So, OK, obviously the musical backing is not comparable with that of the late-60’s/early 70’s American or Malaco studios, but just listen to Oscar still using all his gospel-derived vocal phrasing to superb effect as he eats his heart out with remorse for having done his girl wrong.

I’m Sorry which proved that even genuine deep soul could survive into the new millennium. So, OK, obviously the musical backing is not comparable with that of the late-60’s/early 70’s American or Malaco studios, but just listen to Oscar still using all his gospel-derived vocal phrasing to superb effect as he eats his heart out with remorse for having done his girl wrong.

In 2008 Oscar somehow got momentarily involved in the Beach Music/’Shag’ Dance scene when he cut the 12-track CD “Over At Mary’s Place” for Ripete (#2383), duetting with Cliff Ellis, the Head Basketball Coach of Coastal Carolina University and long-term Beach Music fan. This one is not for the fainthearted!

In 2008 Oscar somehow got momentarily involved in the Beach Music/’Shag’ Dance scene when he cut the 12-track CD “Over At Mary’s Place” for Ripete (#2383), duetting with Cliff Ellis, the Head Basketball Coach of Coastal Carolina University and long-term Beach Music fan. This one is not for the fainthearted!

The following year, Oscar would return to the Porretta Terme Festival, 10 years on from his first visit there, but the videos of him performing, which you can readily find on You Tube, suggest that his voice was no longer quite what it was and, as the clips are filmed from the audience, the sound quality is poor anyway, plus there is much extraneous noise.

The same year, Oscar duetted with Susie Ann Blackwells on the 5+ minute single-track “That Stuff”, a repetitious, though strangely haunting slow-paced soulful piece, on which Susie and Oscar promise they “ain’t messin’ with that stuff no more” – we can only guess what “that stuff” might be. Surely not ‘drugs’, Mr Toney – not if Mighty Sam is to be believed!

It’s nice to be able to recognise in Oscar Toney Jr. a genuine southern-soul hero who, at time of writing, is not only very much still with us but still performing. Long may that continue.

UPDATE ~ Ady Croasdell has kindly written that he has discovered the following info on Oscar's early recordings:-

UPDATE ~ Ady Croasdell has kindly written that he has discovered the following info on Oscar's early recordings:-

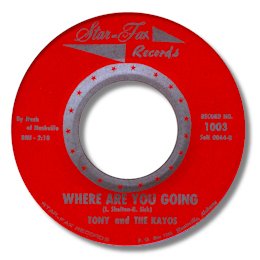

Oscar Toney Jr’s first solo recording was his initial King release "You’re Going To Need Me" / "‘Can It All Be Love" recorded in April 1964 and issued as King 5906. It was recorded in Macon, Georgia and though it did not sell many copies, the company put him back in the studio in February 1965 to cut ‘Keep On Loving Me’ and ‘I’ve Found A True Love’. The musicians on both sessions were Edward Ballard, Hal Mitchell (tp), Sonny Williams, Bobby Robinson (ts), Joe Williams (g), David Trice (b) and Howard Hewley (dms) and were known as the Kayos Band. The record company declined to issue the second session until July 1967, two months after Oscar entered the charts with his version of ‘For Your Precious Love’ which would eventually zoom to #4 R&B. The two year old King recording failed to sell in any quantity while two more of his Bell recordings were R&B hits. In researching this piece, I came across a 45 by Tony & The Kayos on the Star-Fax label, from Huntsville in Oscar’s home state of Alabama. This must be his first record billed as a featured vocalist, as previous efforts with the vocal group the Searchers (also backed by the Kayos), went unheralded on the Mac label.

Sir Shambling adds ~ I'm fortunate enough to have that Tony & The Kayos 45. And while "The Kangaroo" is as forgettable a piece of dance music as it's name would suggest, the other side ![]() "Where Are You Going" is a fine R & B ballad. Oscar's unmistakeable voice is in really fine shape, his high "crying" tone soaring over the vamping band. My copy of this 45 is Radio Station date stamped as "Aug 19 1963".

"Where Are You Going" is a fine R & B ballad. Oscar's unmistakeable voice is in really fine shape, his high "crying" tone soaring over the vamping band. My copy of this 45 is Radio Station date stamped as "Aug 19 1963".

Note ~ You can find a very good Oscar Toney Jr discography at Heikki Suosalo's excellent Soul Express website here.