| Home | Artists | Articles | Links | Contact |

Quin Ivy And His Norala And Quinvy Studios, Part 3: The Busy First Six Months Of 1967

by Pete Nickols

Throughout 1966 Quinon R. Ivy and his little Norala studio had had to concentrate almost exclusively on satisfying Atlantic’s (and the public’s) need to hear Percy Sledge, further to the huge success of his first-ever recording early in that year. This had meant giving over nearly all main studio time to recording Percy as and when his hectic schedule of tours and personal appearances allowed. However, with some of what would become Percy’s early 1967 releases already ‘in the can’ (see Part 2), the dawning of the new year allowed Quin Ivy to ‘take stock’ and to look for other artists to meaningfully make use of Norala, in addition, of course, to continuing to satisfy the need for new Sledge recordings and Atlantic’s desire also to have him cut some tracks that year by two of their own established Atco artists (see later).

One of the first things Quin had to address was a deal he was about to strike with Atlantic’s Atco subsidiary that they would distribute any Ivy artists who were considered good enough for potential national exposure. The means for this would be a new Ivy label, South Camp, which would also see the demise of the Norala imprint. The hope was obviously to try to find another potential ‘Percy Sledge’ who would be transformed from a southern obscurity to a household name. Sadly this would not happen but neither the optimistic Ivy nor Atlantic/Atco knew that when they concluded the deal, as confirmed in a Billboard article of 11th February 1967.

One of the first things Quin had to address was a deal he was about to strike with Atlantic’s Atco subsidiary that they would distribute any Ivy artists who were considered good enough for potential national exposure. The means for this would be a new Ivy label, South Camp, which would also see the demise of the Norala imprint. The hope was obviously to try to find another potential ‘Percy Sledge’ who would be transformed from a southern obscurity to a household name. Sadly this would not happen but neither the optimistic Ivy nor Atlantic/Atco knew that when they concluded the deal, as confirmed in a Billboard article of 11th February 1967.

As you can see from the report, it was also intended that the sadly forever obscure June Edwards would have the honour of the first South Camp release by the end of February. Now June had already cut three tracks at Norala as early in 1967 as 6 January. This session was produced by Spooner Oldham and it threw up one unissued track (“What A Surprise”) and two fine country-soul performances which, strangely, did not go to make up the first South Camp 7001 single but would only see release at the very end of the year on South Camp 7008. The delay may in part have been caused by the need to re-cut (or satisfactorily finish) the 6 January recording of country-star Loretta Lynn’s “You Ain’t Woman Enough (To Take My Man)”, something which didn’t take place until a much later two-day session on 7 and 8 May.

Certainly the finished tracks would have been strong enough to issue earlier had they both been ‘ready’, June providing an excellent interpretation of Dan Penn’s lyrical ballad “Close To Me”, which its writer had himself already cut for Fame (no. 6402), and also a fine, deep, meaningful, soul-meets-country version of the Loretta Lynn song, which the country-singer-songwriter had herself taken at a very much jauntier pace.

However, the two Edwards tracks which did feature on South Camp 7001 never appeared on any Ivy session-sheet. These were Penn and Oldham’s lovely deep opus “My Man (My Sweet Man)” and the bouncier, up-tempo Spooner Oldham song “Heaven Help Me (I’m Falling In Love With You)”. Exactly when this 45 was issued is also not known. Either these tracks were already ‘in the can’ by the time of the Billboard announcement, having perhaps been recorded even before the 6 January session, or else the intention had been to issue the sides cut at that 6 January session as the first release but the need to finish or re-cut one of them had caused a re-think and the need therefore to record two more sides to include on South Camp 7001. Pinpointing even approximate South Camp release dates is not easy since Ivy did not issue his South Camp singles entirely in numerical order. It’s probable that June Edwards 7001 release pre-dated Don Varner’s 7003 release (see later) which appeared in June. However, the two songs which go to make up what one would have expected to be the intervening 7002 release were not even recorded until November, while issue 7007, for instance, was released in Mid-September! (see next Part).

However, the two Edwards tracks which did feature on South Camp 7001 never appeared on any Ivy session-sheet. These were Penn and Oldham’s lovely deep opus “My Man (My Sweet Man)” and the bouncier, up-tempo Spooner Oldham song “Heaven Help Me (I’m Falling In Love With You)”. Exactly when this 45 was issued is also not known. Either these tracks were already ‘in the can’ by the time of the Billboard announcement, having perhaps been recorded even before the 6 January session, or else the intention had been to issue the sides cut at that 6 January session as the first release but the need to finish or re-cut one of them had caused a re-think and the need therefore to record two more sides to include on South Camp 7001. Pinpointing even approximate South Camp release dates is not easy since Ivy did not issue his South Camp singles entirely in numerical order. It’s probable that June Edwards 7001 release pre-dated Don Varner’s 7003 release (see later) which appeared in June. However, the two songs which go to make up what one would have expected to be the intervening 7002 release were not even recorded until November, while issue 7007, for instance, was released in Mid-September! (see next Part).

Sadly, whenever it was released in 1967, there was little public interest in June Edwards’ first South Camp forty-five. There is also an indication in an Atlantic-related discography that a further unissued track by her (viz. “I Do” – master no. 11713) was cut at Norala on 16 February, though, again, there is no Ivy session sheet for this date.You can hear June Edwards' two fine country soul ballads here.

By February of ’67 a certain Eddie Hinton had made his first appearance at Ivy’s studio along with his pal Paul Ballenger. Hinton, born in 1944 in Jacksonville Florida but raised, after a parental divorce, in Tuscaloosa, Alabama had played in a local group called The Spooks before he first met Ballenger in the early 60’s when joining a group who also toured the Tuscaloosa area called The 5-Men-Its for whom Ballenger had been vocalist and keyboardist. Once Eddie joined up he got to take over vocal duties and Ballenger then left. It was effectively this group that Eddie himself would also later leave, aged 22, to move to Muscle Shoals, The Men-Its then becoming Hour Glass and, with the addition of Gregg and Duane Allman, moving to LA to record for Liberty Records.

Fellow 5 Men-Its musician Paul Hornsby said of Hinton at the time: “As for Eddie Hinton, books could be written about him alone! Eddie was the ‘blackest white boy’ I ever knew. He had a vocal and guitar style I haven't heard since. Other than his music style, Eddie was in a club all by himself. No one else seemed to be invited. On the road, he always drove his own car by himself. The rest of us car-pooled. He preferred it that way. It wasn't that we didn't get along. He was just very much a loner. Hinton was one of those guys that just had charisma. In a room full of people, he stood out. That also carried across on stage.”

Ballenger’s musical grounding had been as a Birmingham, Alabama rockabilly artist, cutting two 45s and a couple of other sides in 1959 and 1960 with his group The Flares for Homer Milan’s Reed label. (If you like rockabilly, his very good “I Hear Thunder” on Reed 1030 can be found on You Tube).

Ballenger’s musical grounding had been as a Birmingham, Alabama rockabilly artist, cutting two 45s and a couple of other sides in 1959 and 1960 with his group The Flares for Homer Milan’s Reed label. (If you like rockabilly, his very good “I Hear Thunder” on Reed 1030 can be found on You Tube).

From his new Shoals base, Hinton began to appear regularly at Quinvy through 1967 and he would write many songs, often with Ballenger, while the pair would also form the publishing company Ruler Music. The two also began undertaking occasional production work using the name Sunalee Productions, especially for the next act to record at Quinvy after June Edwards, namely Don Varner, whose 19 February session saw him recording Hinton and Greene’s fine ![]() “Down In Texas” (a song also later cut by Oscar Toney Jr. in Memphis) which would become Varner’s debut release for Ivy in June that year on South Camp 7003 (it was a Billboard R&B Chart prediction on 10 June, though sadly such success didn’t materialise). Hinton also penned (and co-produced with Ballenger) what would become its flip-side, the lively “Masquerade”. Two unissued-at-the-time Varner tracks were the chiefly up-tempo “When It’s Over” and Don’s very good cover of Joe Tex’s “Meet Me In Church”, which Ivy much later (in 1968) would unsuccessfully try to get released on the UA subsidiary, Veep, where it was earmarked for Veep1296.

“Down In Texas” (a song also later cut by Oscar Toney Jr. in Memphis) which would become Varner’s debut release for Ivy in June that year on South Camp 7003 (it was a Billboard R&B Chart prediction on 10 June, though sadly such success didn’t materialise). Hinton also penned (and co-produced with Ballenger) what would become its flip-side, the lively “Masquerade”. Two unissued-at-the-time Varner tracks were the chiefly up-tempo “When It’s Over” and Don’s very good cover of Joe Tex’s “Meet Me In Church”, which Ivy much later (in 1968) would unsuccessfully try to get released on the UA subsidiary, Veep, where it was earmarked for Veep1296.

This 19 February Varner session was the first on which Hinton is listed as a Quinvy musician, playing the bass lines behind and beneath Junior Lowe’s and Marlin Greene’s guitar runs. He also began his regular habit of cutting demos of his songs, including one of “Down In Texas” (featured on the 2004 Zane Records’ “Playin’ Around” CD).

Don Varner had been born on 25 June 1943 in Birmingham Alabama. Raised as a catholic, he had been influenced not by gospel, R&B or blues singers but chiefly by white, deep-voiced crooners like Tennessee Ernie Ford and Perry Como, so that when he did eventually join a gospel group called the Vocalaires, singing non-secular music was something of a new experience for him. Prior to arriving at Quinvy, Don had previously had just the one single in 1965 on Art Grayson’s obscure Birmingham-based Downbeat label (“Here Come My Tears Again”/“I Finally Got Over” – issue no. 102).

Don Varner had been born on 25 June 1943 in Birmingham Alabama. Raised as a catholic, he had been influenced not by gospel, R&B or blues singers but chiefly by white, deep-voiced crooners like Tennessee Ernie Ford and Perry Como, so that when he did eventually join a gospel group called the Vocalaires, singing non-secular music was something of a new experience for him. Prior to arriving at Quinvy, Don had previously had just the one single in 1965 on Art Grayson’s obscure Birmingham-based Downbeat label (“Here Come My Tears Again”/“I Finally Got Over” – issue no. 102).

Nine days after Varner’s session, on 28 February, the prolific label-hopping recording artist Austin Taylor, originally from Oklahoma and better known as Ted Taylor, found his way to Quinvy Studio as, after several unsuccessful Atco 45s, clearly Jerry Wexler felt it was time to see what some Quinvy ‘magic’ could do to increase sales for his high-voiced soul-man. (Atlantic discographies often wrongly date this session as 10th April and some even try to pretend it was a New York City event!).

With Greene and Ivy producing, Taylor cut 6 songs. “Heart Of A Child”, “Moving On Down The Line”, “Talking With The Devil” and “Poor Papa Cooper” remained unissued at the time, while Penn and Oldham’s gorgeous lay-back country-soul song ![]() “Feed The Flame”, coupled with “Baby Come Back To Me”, would see release on Atco 6481. Sadly this 45 would also fail to chart, demonstrating yet again that quality doesn’t always equate with commercial success and, after this failure, Taylor said goodbye to Atco and moved on to Stan Lewis’ Shreveport-based Jewel and Ronn labels, even then taking more than another two years before finally making his next dent in the national R&B Chart.

“Feed The Flame”, coupled with “Baby Come Back To Me”, would see release on Atco 6481. Sadly this 45 would also fail to chart, demonstrating yet again that quality doesn’t always equate with commercial success and, after this failure, Taylor said goodbye to Atco and moved on to Stan Lewis’ Shreveport-based Jewel and Ronn labels, even then taking more than another two years before finally making his next dent in the national R&B Chart.

After hosting Atco’s Ted Taylor, Ivy’s next job was to keep his New York client-company sweet (and to try to keep the dollars rolling in) by cutting another much-needed session on star attraction Percy Sledge.

After hosting Atco’s Ted Taylor, Ivy’s next job was to keep his New York client-company sweet (and to try to keep the dollars rolling in) by cutting another much-needed session on star attraction Percy Sledge.

There was no urgency for a new single as “Out Of Left Field” was only just being released, but Atlantic wanted another album and so Ivy and Sledge set-to for a full week of recording between 7 and 13 March, with Eddie Hinton joining Oldham, Hawkins, Hood, Greene and Jerry Weaver on musical duties. Once again there was no time for ‘new’ songs and Atlantic settled merely for all eleven of the ‘covers’ Percy put down at this session, the album “The Percy Sledge Way” (Atlantic 8146) not even containing an existing Sledge hit-single to help sales along. Every one of the songs was a ballad and three of the tracks would see single release. Percy’s version of Chuck Willis’ “What Am I Living For” would be paired with the previously-recorded “Love Me Tender” on Atlantic 2414 as the follow-up single to “Out Of Left Field” but it would be “Love Me Tender” which would make no.35 on the R&B chart and 40 on the Pop chart that summer, although Pop sales were split, with “What Am I Living For” also making no.91 in its own right. Next, Percy’s cover on the LP of the country song “Just Out Of Reach” (arguably the first-ever soul hit when cut by Solomon Burke in 1961) would be paired with “Hard To Believe” (from Percy’s next session at Quinvy - see later) on Atlantic 2434. This single would chart only on the Pop Hot 100, peaking at a lowly No.66. Then there was Percy’s melodic, if somewhat schmaltzy take on Joe Simon’s “My Special Prayer” (to be issued in late 1968 as a single on Atlantic 2594). This song would become a favourite with his many fans (especially so in South Africa where Sledge would later tour and achieve great popularity and also in Holland where it hit the No.1 spot).

The LP itself would creep into the lower reaches of Billboard’s Top 200 album chart that August for a mere 3 weeks, peaking at only No.178. Of the other ‘covers’, most of which were to a very good standard, perhaps the finest was chosen to open the LP, namely one of the best versions of Penn and Oldham’s

The LP itself would creep into the lower reaches of Billboard’s Top 200 album chart that August for a mere 3 weeks, peaking at only No.178. Of the other ‘covers’, most of which were to a very good standard, perhaps the finest was chosen to open the LP, namely one of the best versions of Penn and Oldham’s ![]() “The Dark End Of The Street”, which had only entered the national charts by James Carr (Goldwax 317) a month earlier. I have a feeling that if Carr’s wonderful version had never been issued, Sledge’s would still have been good enough for successful single release.

“The Dark End Of The Street”, which had only entered the national charts by James Carr (Goldwax 317) a month earlier. I have a feeling that if Carr’s wonderful version had never been issued, Sledge’s would still have been good enough for successful single release.

Around this time, Ivy realised that not all of his recordings might be accepted for national distribution by Atco and so, feeling that there would be at least a local and/or regional market for such product, he formed a second in-house label, Quinvy, which, contrary to much previous ‘thinking’ was never given national distribution by Atlantic, or anyone else, beyond the restricted geographical limits of Ivy’s own promotional clout. In fact, Atco’s support for the main South Camp 7000 series of recordings was short-lived once it found that the records were not ‘breaking’ nationally (see later Part), whether or not this was at least partly down to their own lacklustre promotion. This is why some future Quinvy product (see later Parts) which didn’t obtain release on an Atlantic-distributed South Camp 45 (or had done so but had now ‘reverted’ merely to Ivy) was later leased out to other labels such as Revue, Tower, Uni and Chess, who could indeed offer wider exposure.

Ivy had already used the Quinvy name for his in-house publishing company - note that Pronto-Quinvy appears as publisher even as early as on Sledge’s ”When A Man Loves A Woman“ 45. Now, in addition to forming a label of that name, he also decided to apply the same name to his 104 E. Second Street Studio, previously known as Norala. Many folk have long thought that Quinvy only referred to Ivy’s second studio at 1307 Broadway, to which he would re-locate in 1968 (see later Part). However, two references justify my assertion that Norala became Quinvy in 1967, well before the new studio was opened. Firstly, the Rhino retrospective CD of Sledge material shows an alleged 6 April 1967 session as being held at Quinvy (not Norala) and, secondly and even more conclusively, the back-sleeve of Frenchman Eddy Mitchell’s Barclay EP shows the tracks therein were cut between 26 and 28 May 1967 (see later - Ivy’s sheet shows 25 and 26 May) but once again at Quinvy (not Norala) and here the ‘re-naming’ of the original studio is confirmed by the fact that the address is also provided and is still described as 104 E. Second Street.

Phil & Alan Walden, Percy Sledge, Jimmy Hughes & Quin Ivy outside Redwal Offices in Macon Ga.

Phil & Alan Walden, Percy Sledge, Jimmy Hughes & Quin Ivy outside Redwal Offices in Macon Ga. In time, Ivy would open his Quinvy studio to an increasing number of ‘wannabes’ who were drawn to it by his astounding success with Percy Sledge. This would even create a need for someone to look after artist management, and that would be the Walden brothers, Phil and Alan, who had set up both Redwal Publishing and Hustlers Management, based in Macon, GA. Indeed, they had already been managing Percy Sledge even from before the time of his second single “Warm And Tender Love”. They had quite a strong roster of existing talent too, including Otis Redding and Jimmy Hughes.

So things were certainly moving fast at what we shall now call Quinvy. So fast that perhaps at this point in Ivy’s career, even Rick Hall was ‘looking over his shoulder’. Some sources suggest Ivy’s relationship with Rick Hall soured after the success of Sledge’s first hit and Ivy himself is quoted as saying “it started out that I was going to do some inconsequential business down here in this little spit-and-baling-wire studio. Then all of a sudden I cut a big hit record. Suddenly (Rick and I were) competing for musicians ‘cause we’re trying to use the same (ones). I don’t know whose fault it was that we grew apart….I don’t know what happened. We got so involved doing our own thing that we just didn’t see each other anymore.”

Well, maybe Ivy and Hall did end up going their separate ways but, even if they ceased to socialise locally, they ended up attending several Atlantic ‘bashes’ together and Ivy certainly managed to retain regular use of Messrs Johnson, Oldham, Hawkins, Hood etc., since his studio session sheets clearly show that these musicians played on nearly all of his sessions right up until the time in April 1969 that they (Barry Beckett having then replaced Spooner Oldham) defected to start running their own Muscle Shoals Sound Studio (see later Part). This also pooh-poohs the oft–quoted allegation that Jimmy Johnson left Norala for Fame as early as 1966 after being offended by his lack of a significant paycheck for his part in the Percy Sledge “When A Man…” session. Whatever his views on that, the fact is Johnson clearly continued to play regularly on Ivy’s sessions (as well as at Fame) throughout 1967 and 1968.

Anyway, back in the early Spring of 1967, Ivy had already decided that Don Varner’s tracks laid down in February were worthy of national promotion via later release (in June on South Camp 7003) and he would decide similarly about two other Varner tracks “Home For The Summer” and “The Sweetest Story”, which by now had probably also been recorded (we have no session details for these tracks) and which would make up South Camp 7005. Similarly, two tracks by Mickey Buckins (see Part 1 for details about Buckins), namely “Seventeen Year Old Girl” and “Long Long Time”, were probably also recorded in the Spring of ’67 (again we have no session details) and these would emerge later on South Camp 7004. The Buckins countrified rock ‘n roll tracks would mean little to soul fans but Varner’s “Home For The Summer” is a fine piece of dramatic deep-soul with the back-up girls and the rhythm section in fine form, plus some nice string overdubs. This original version is arguably superior to Jimmy Braswell’s March 1970 recording, also for Quin Ivy (see later Part). Varner’s “The Sweetest Story” is a strong, rolling-paced piece with a prominent and very Stax-like horn arrangement.

So, with this South Camp material ‘in the can’, all Quin needed now was something with which to ‘kick off’ his new Quinvy label. Perhaps The Wee Juns’ tracks were already in the can (we can’t say because there are once again no session sheets for them) but what a disappointment this first Quinvy release would prove to be. Despite being produced by Donnie Fritts and Jimmy Johnson, The Wee Juns’

So, with this South Camp material ‘in the can’, all Quin needed now was something with which to ‘kick off’ his new Quinvy label. Perhaps The Wee Juns’ tracks were already in the can (we can’t say because there are once again no session sheets for them) but what a disappointment this first Quinvy release would prove to be. Despite being produced by Donnie Fritts and Jimmy Johnson, The Wee Juns’ ![]() “Out Of The Clear Blue Sky” and “I Spy” were both straight-ahead ‘white-boy pop’ performances almost reminiscent of the style that the lesser British Merseybeat groups had employed back in around 1964-5. This attempt at pure pop appeal duly appeared on Quinvy 167 (with 6701 and 6702 matrices) and promptly sank without trace. It seems the youngsters did manage to convince someone else to record them as they had “Way Down” and “With Your Love” coupled together on the obscure Indiana-based Skoop label (issue no. 1068). At least, I am assuming that surely there can’t have been two groups with a name like The Wee Juns!

“Out Of The Clear Blue Sky” and “I Spy” were both straight-ahead ‘white-boy pop’ performances almost reminiscent of the style that the lesser British Merseybeat groups had employed back in around 1964-5. This attempt at pure pop appeal duly appeared on Quinvy 167 (with 6701 and 6702 matrices) and promptly sank without trace. It seems the youngsters did manage to convince someone else to record them as they had “Way Down” and “With Your Love” coupled together on the obscure Indiana-based Skoop label (issue no. 1068). At least, I am assuming that surely there can’t have been two groups with a name like The Wee Juns!

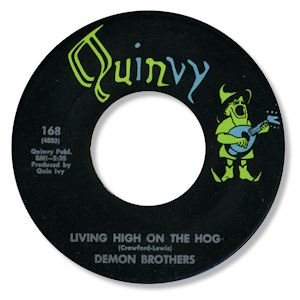

Ivy’s second Quinvy release fared no better. Almost certainly an item Ivy had already ‘bought-in’ (I know not from where), The Demon Brothers’ two-sider on Quinvy 168 at least offered up two pacy pieces of fairly funky soul but ![]() “High On The Hog” (to be cut actually at Quinvy a year later by Tony Borders) and “Uh Huh” merely conspired to banish the Demon boys to permanent obscurity. Could their names be "Crawford" and "Lewis" from the writing credits of both sides of their 45?

“High On The Hog” (to be cut actually at Quinvy a year later by Tony Borders) and “Uh Huh” merely conspired to banish the Demon boys to permanent obscurity. Could their names be "Crawford" and "Lewis" from the writing credits of both sides of their 45?

Apart from June Edwards’ aforementioned finishing-off (or re-cut) of “You Ain’t Woman Enough (To Take My Man) on 7 and 8 May, the next major session at Quinvy was on 17 May. This was to be the first recording session anywhere for the ‘almost local’ Huntsville, Alabama born Bill Brandon, clearly a prime example of Ivy’s new-found success attracting would-be stars to his little studio. Sadly Brandon would never attain national commercial success apart from one minor soul hit for Moonsong in 1972 and a small disco hit for Prelude in 1978 but he was just one of several aesthetically genuinely soulful artists who would find their way to Quin Ivy’s door. Of the four tracks he cut that May at Quinvy, “Self Preservation” is 6/8 deep country-soul of a high order. This would be coupled with the potent driving soul of “Full Grown Lovin’ Man” on a South Camp 45 (7006) to be issued later in the year, while in August 1968, Percy Sledge would himself cut “Self Preservation” (see later Part) for release on Atlantic 2563. The other two Brandon tracks were the trillionth version of Buddy Johnson’s hoary old 1948 song “Since I Fell For You” and the good, if blues-influenced “Strangest Feeling”, these two sides later making up a Quinvy 7007 release, Brandon’s version of the latter item pre-dating Ted Taylor’s Ronn 29 interpretation by some two years. Brandon would return to Quinvy the following March and we shall catch up with him then; you can find out more on Bill Brandon's music and illustrious career here.

Apart from June Edwards’ aforementioned finishing-off (or re-cut) of “You Ain’t Woman Enough (To Take My Man) on 7 and 8 May, the next major session at Quinvy was on 17 May. This was to be the first recording session anywhere for the ‘almost local’ Huntsville, Alabama born Bill Brandon, clearly a prime example of Ivy’s new-found success attracting would-be stars to his little studio. Sadly Brandon would never attain national commercial success apart from one minor soul hit for Moonsong in 1972 and a small disco hit for Prelude in 1978 but he was just one of several aesthetically genuinely soulful artists who would find their way to Quin Ivy’s door. Of the four tracks he cut that May at Quinvy, “Self Preservation” is 6/8 deep country-soul of a high order. This would be coupled with the potent driving soul of “Full Grown Lovin’ Man” on a South Camp 45 (7006) to be issued later in the year, while in August 1968, Percy Sledge would himself cut “Self Preservation” (see later Part) for release on Atlantic 2563. The other two Brandon tracks were the trillionth version of Buddy Johnson’s hoary old 1948 song “Since I Fell For You” and the good, if blues-influenced “Strangest Feeling”, these two sides later making up a Quinvy 7007 release, Brandon’s version of the latter item pre-dating Ted Taylor’s Ronn 29 interpretation by some two years. Brandon would return to Quinvy the following March and we shall catch up with him then; you can find out more on Bill Brandon's music and illustrious career here.

On 23 and 24 May, Atlantic favoured Quin with another visiting artist, this time New Yorker Ben E. King. As had been the case with Ted Taylor, Ivy and Greene would share production duties with Marlin also doing the arrangements. King cut five songs at Quinvy, two of which, Marlin and Jeanie Greene’s very appealing and emotively-performed mid-pacer

On 23 and 24 May, Atlantic favoured Quin with another visiting artist, this time New Yorker Ben E. King. As had been the case with Ted Taylor, Ivy and Greene would share production duties with Marlin also doing the arrangements. King cut five songs at Quinvy, two of which, Marlin and Jeanie Greene’s very appealing and emotively-performed mid-pacer ![]() “Don’t Take Your Sweet Love Away” and Dr. John and Jessie Hill’s lay-back soul-ballad “She Knows What To Do For Me”, made it on to both sides of an Atco 6527 release. This latter song also saw country release by Loretta Lynn and in October 1968, Bill Brandon would cut an even more overtly soulful unissued-at-the-time version for Quin Ivy (see later Part).

“Don’t Take Your Sweet Love Away” and Dr. John and Jessie Hill’s lay-back soul-ballad “She Knows What To Do For Me”, made it on to both sides of an Atco 6527 release. This latter song also saw country release by Loretta Lynn and in October 1968, Bill Brandon would cut an even more overtly soulful unissued-at-the-time version for Quin Ivy (see later Part).

The three other King songs cut that day, “Think It Over”, “Can’t Wait Much Longer” and “Standing Room Only”, remained unissued at the time. Once again there was to be no chart success for the single and one has to wonder if Atlantic was giving enough promotion to these fine Quinvy recordings.

Quite how and why the two French ex-rock ‘n rollers Eddy Mitchell and Dick Rivers attended sessions at Quinvy in 1967 remains something of a mystery. What’s more, although they were good friends, they did not arrive at the same time, nor were they touring the States together. We’ll come to Dick Rivers in our next Part as he didn’t reach Sheffield until the end of October, but Eddy Mitchell had a two-day session at Quinvy on 25 and 26 May (although the 1967 French Barclay LP and EP which include tracks from these sessions both date them as being cut between 26 and 28 May).

Mitchell was born Claude Moine in Paris in 1942. He left school at 14 to start work in a bank but began his rock ‘n roll career in the late 50’s at the Paris niterie Le Golf Drouot where he became known as “Schmoll”. Soon he would form a group at first called Les Five Rocks but in 1960 when they were signed to the French Barclay label they were re-christened Les Chaussettes Noires (The Black Socks). In 1961 they released 6 singles and sold 2 million records. After his military draft, Mitchell went solo from 1963 and cut the album “Eddy In London” with a very young Jimmy Page in attendance. Further sets followed and by 1965 he had decided to try his hand at R&B/soul by releasing his “Du Rock ‘n Roll Au Rhythm ‘n Blues” album together with a potent horn section. His more pensive “Seul” (“Alone”) LP, cut once again in London in 1966, proved to be only an interlude before he made his visit to Quinvy, leading to the issue of his misleadingly titled “De Londres A Memphis” album (issued on French Barclay 80 351 in October 1967), which actually comprised 6 tracks cut at the Pye studios in London in both February and June that year plus the seven tracks which Mitchell cut at Quinvy in May (no Memphis connection there, then!). Four of the seven Quinvy tracks even saw French release as soon as late-June on the “Chacun Pour Soi” (“Every Man For Himself”) EP on French Barclay 71 185, which strangely was issued with two quite different front-covers.

Mitchell was born Claude Moine in Paris in 1942. He left school at 14 to start work in a bank but began his rock ‘n roll career in the late 50’s at the Paris niterie Le Golf Drouot where he became known as “Schmoll”. Soon he would form a group at first called Les Five Rocks but in 1960 when they were signed to the French Barclay label they were re-christened Les Chaussettes Noires (The Black Socks). In 1961 they released 6 singles and sold 2 million records. After his military draft, Mitchell went solo from 1963 and cut the album “Eddy In London” with a very young Jimmy Page in attendance. Further sets followed and by 1965 he had decided to try his hand at R&B/soul by releasing his “Du Rock ‘n Roll Au Rhythm ‘n Blues” album together with a potent horn section. His more pensive “Seul” (“Alone”) LP, cut once again in London in 1966, proved to be only an interlude before he made his visit to Quinvy, leading to the issue of his misleadingly titled “De Londres A Memphis” album (issued on French Barclay 80 351 in October 1967), which actually comprised 6 tracks cut at the Pye studios in London in both February and June that year plus the seven tracks which Mitchell cut at Quinvy in May (no Memphis connection there, then!). Four of the seven Quinvy tracks even saw French release as soon as late-June on the “Chacun Pour Soi” (“Every Man For Himself”) EP on French Barclay 71 185, which strangely was issued with two quite different front-covers.

The back-covers of both EPs were identical and showed a list of the personnel present at Quinvy, along with that tell-tale name and address of the studio as “Quinvy” at 104 E. Second Street. If you look at the image relating to Mitchell’s LP, tracks 7 to 13 will show you all that was cut by him at Quinvy and it’s fair to say these were not really strong soul songs at all, five being penned by Mitchell himself (as C. Monk – along with his friend, pianist and regular writing partner Peter Papadiamandis), one by another French threesome, and just one being an adaption by Mitchell and Spooner Oldham of an Eddie Hinton song. The Quinvy-cut tracks were mixed for Barclay by .jpg) Atlantic in New York. The big French hit for Eddy from his Quinvy session was

Atlantic in New York. The big French hit for Eddy from his Quinvy session was ![]() “Alice”, a pleasant enough soulful ballad though hardly strong enough to rival the best US product of the day. Mitchell is still active and can be regarded as something of a French counterpart to the UK’s Cliff Richard – an early would be-rocker who failed to conquer the USA and who branched out into other music and into film to become something of a national institution with still enough of a following in his late sixties to fill a concert hall.

“Alice”, a pleasant enough soulful ballad though hardly strong enough to rival the best US product of the day. Mitchell is still active and can be regarded as something of a French counterpart to the UK’s Cliff Richard – an early would be-rocker who failed to conquer the USA and who branched out into other music and into film to become something of a national institution with still enough of a following in his late sixties to fill a concert hall.

The final Quinvy sessions of a very busy first-half to 1967 were reserved for Percy Sledge, nine tracks being cut on 13 and 14 June. One, “Try Me”, remained ‘in the can’. Two other tracks would see only single release: “Faithful And True” (a song also cut later for Quinvy by Z.Z.Hill – see later Part) would eventually be paired with “True Love Travels On A Gravel Road” on a 1969 Atlantic 2679 forty-five; while “Hard To Believe” (as previously mentioned) would be the flip of “Just Out Of Reach” on Atlantic 2434. Yet three more tracks would feature both on Percy’s 1968 album “Take Time To Know Her” (Atlantic 8180) and as later singles. These were “It’s All Wrong But It’s Alright” (to be the flip of the 1968 45-release of “Take Time To Know Her” on Atlantic 2490), “Between These Arms” (to be the flip of “Sudden Stop” again in 1968 on Atlantic 2539) and “Come Softly To Me” (which would appear in 1970 together with “Help Me Make It Through The Night” on one or two different versions of Atlantic 2754). That left three album-only tracks from the session, namely Percy’s own version of Ted Taylor’s “Feed The Flame”, “Spooky” and “High Cost Of Leaving”.

We’ll discuss the album in a later Part as it featured some tracks not yet recorded as early as June 1967 but, of the songs put down at this particular Sledge session, Donnie Fritts’ and David Briggs’ “High Cost Of Leaving” was a fine example of storyline-soul, while “Between These Arms” was a gorgeously slow-paced lay-back piece of country-soul balladry, with some superbly sympathetic organ support by Spooner Oldham. Sledge’s interpretation of “Faithful And True” is also outstanding but arguably even better was the genuinely deep Marlin Greene/Eddie Hinton composition ![]() “It’s All Wrong But It’s Alright”. Again, Hinton cut a demo of this gem (featured on the Zane “Dear Y’All” CD from 2000) but the superb finished product was down to Sledge’s great soulful phrasing.

“It’s All Wrong But It’s Alright”. Again, Hinton cut a demo of this gem (featured on the Zane “Dear Y’All” CD from 2000) but the superb finished product was down to Sledge’s great soulful phrasing.

We shall deal with the second half of 1967 at Quinvy in the next Part.

UPDATE ~ Re Ted Taylor’s “Baby Come Back To Me”, Bobby Harris made an even ‘deeper’ soul impression with his terrific version of the song on Shout 210, also dating from early 1967. We really can’t be sure which version was recorded first but my money is actually on Bobby Harris. Here’s the (admittedly circumstantial) evidence in support of my ‘informed guess’.

Firstly, the songwriters, like Harris and his label, were from the Big Apple (not from the south as on “Feed The Flame”) and the NY-based Bert Berns would probably have been an early port-of-call for those established local songwriters, or their ‘song-plugger’.

Then, Harris’ ‘A’ side, “The Love Of My Woman” – his version of Ed Townsend’s great song “The Love Of My Man” – was reviewed in the Top 10 R&B Spotlight column of Billboard as early as 18th March 1967. It also appeared 3 weeks later merely as an R&B chart prediction in Billboard’s 8th April 1967 edition. Meanwhile, Ted Taylor’s “Feed The Flame” (the ‘A’ side of his version of “Baby Come Back To Me”) did not receive this same accolade in Billboard until its 27th May 1967 edition.

I also find it hard to believe that Atco could have had Ted Taylor’s 45 on the market any sooner, bearing in mind the track wasn’t even cut down south in Sheffield until the very last day of February. Indeed the Atlantic discography itself wrongly dates Taylor’s session as late as 10th April 1967 and, even though it also wrongly quotes a New York location, all six songs listed as recorded that day are indeed the same six as on the Quinvy sheet for 28th February – so, in reality, 10th April was probably around the time master numbers were awarded by Atlantic to those six tracks and perhaps a release number to the two tracks chosen to make up the Taylor single - which theory would tie in with Billboard’s review of it not being until 27th May.

So it seems pretty certain that Bobby Harris’ single was first to the marketplace, although whether his version of “Baby Come Back To Me” was actually recorded before Taylor’s, we still can’t be 100 per cent sure.

NEW UPDATE ~ We have no reason to doubt most of the Quinvy session sheets in our possession (albeit they do not cover every session at the studio) yet the Percy Sledge Rhino box-set (issued after Parts 1 to 5 of this article were written) often gives different dates (and even locations) for many of Percy’s recordings, presumably based on Atlantic discographical information. There is no reason to assume the Atlantic info. is necessarily more accurate. Sometimes it would seem the Atlantic data may be right (as when it mentions a pre-Fall 1968 stereo recording perhaps at another studio because we now know that the old E Second Street studio was ‘monaural only’) but at other times it could simply be that these alternative dates (usually later) may relate possibly to when Atlantic masters of Quinvy recordings were received and noted rather than when the recording itself was actually laid down in the studio. The truth is, we just don’t know.

(a) The eleven tracks put down by Percy Sledge to make up his “The Percy Sledge Way” LP, which are shown above as having been recorded between 7th and 13th March 1967, are given instead a 6th April 1967 recording date in Sledge’s Rhino box-set. However, this seems unlikely to me if only because one could hardly put down eleven successful new recordings, all good enough for issue on an LP, in one single day! The box-set correctly notes, however, that the album version of “Just Out Of Reach” cut at that session was also edited down at the same time to produce the single version which saw release in August 1967 on Atlantic 2434 (both versions are featured in the box-set).

(b) Re the nine tracks put down by Percy Sledge shown above as having been recorded between 13 and 14 June 1967 – many of these are given different, later dates in Sledge’s Rhino box-set, viz.

“High Cost Of Leaving”, “Hard To Believe” and a stereo version of “It’s All Wrong But It’s Alright” are shown as recorded in “Alabama” on 28th July 1967.

The single version of “It’s All Wrong But It’s Alright” is shown as recorded at an unknown location on 1st February 1968.

“Feed The Flame”, “Come Softly To Me”, “Spooky” and “Between these Arms” (plus a stereo version of “Sudden Stop”) are all shown as recorded in “Alabama” on 15th March 1968.

FURTHER UPDATE ~ It is now known that Penn & Oldham’s song “Feed The Flame” was recorded before Ted Taylor by Otis Redding’s protégé, Billy Young. This Fame recording was unissued at the time but may well see inclusion on an Ace/Kent CD by mid-2013 at the latest as part of that company’s Fame reissue project.

Acknowledgements: John Ridley; Peter Guralnick; Barney Hoskyns; Charles Fuqua; Gilles Petard; Colin Escott; Roben Jones; Emil Ceska, Davie Gordon; Michiel Moll; David Cole/In The Basement; Clive Richardson/RPM-Shout; Gary Cape/Grapevine-Soulscape; Peter Thompson/Zane Records; Soulful Kinda Music; Vintage Soul fanzine; Billboard; Rick Clark/Lynyrd Skynyrd Boxset Booklet; the websites and blogs of many of the artists/personalities featured.

Special thanks to Paul Mooney - all licensing enquiries for Quinvy / South Camp / Broadway Sound masters should be directed to Selrec Ltd and most of the songs are controlled by Millbrand Music Ltd in all territories outside the US and Canada.

FURTHER UPDATE ~ Re: The Wee Juns.

As with most of these early, poor-selling and now quite rare Quinvy ‘house-label’ ‘pop’ singles, the exact date of recording of the Wee Juns’ Quinvy 167 release is not known, although I have seen one quoted for this particular 45 as November 1966. This is quite possible, even though the release number of 167 would suggest the record itself did not emerge until early 1967.

Donnie Fritts wrote The Wee Juns “Out Of The Clear Blue Sky” and he and Jimmy Johnson produced it, as they did the Wee Jun’s version of Bruce Gist and Carroll Quillan’s “I Spy” on the flip. Although not very ‘psychedelic’ to my ears, “I Spy” would much later appear on a 2002 CD in the “Psychedelic States” series put out by the Gear Fab label, which covered one US State at a time, the particular one in question being titled “Alabama In The 60s Volume 2”.

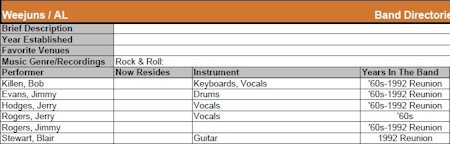

The identity of the Alabama Wee Juns has always been a mystery but at last I think I can throw rather more than a glimmer of light on the matter.

The Alabama Music Hall of Fame indicates the group was founded in Sheffield in around 1962, while elsewhere on the ‘web’ I found their personnel listed as follows: Bob Killen (keyboards and vocals), Jimmy ‘Be Bop’ Evans (drums), Blair Stewart (guitar), Jerry Hodges and Jerry Rogers (both vocals) and Jimmy Rogers (no other details). Now, whilst it seems likely that these guys played in the band at one time or another, it is probably a case of ‘but not all at the same time’. Indeed the group’s membership could have been quite fluid like so many of the early local bands in the Shoals area. This is borne out by a web-contributor who attended ‘sock hops’ which the Wee Juns played near the very beginning of their ‘career’ and he recalls that, back then, Jimmy Johnson and David Hood would often ‘sit in’ with them. This was around the time Johnson was playing also with Hollis Dixon’s Keynotes. The contributor adds, however, that there were always about three or four regular Wee Juns in the group, so it is clear that they were indeed a band rather than, say, a vocal duo or vocal group who always relied on others for musical accompaniment.

The Alabama Music Hall of Fame indicates the group was founded in Sheffield in around 1962, while elsewhere on the ‘web’ I found their personnel listed as follows: Bob Killen (keyboards and vocals), Jimmy ‘Be Bop’ Evans (drums), Blair Stewart (guitar), Jerry Hodges and Jerry Rogers (both vocals) and Jimmy Rogers (no other details). Now, whilst it seems likely that these guys played in the band at one time or another, it is probably a case of ‘but not all at the same time’. Indeed the group’s membership could have been quite fluid like so many of the early local bands in the Shoals area. This is borne out by a web-contributor who attended ‘sock hops’ which the Wee Juns played near the very beginning of their ‘career’ and he recalls that, back then, Jimmy Johnson and David Hood would often ‘sit in’ with them. This was around the time Johnson was playing also with Hollis Dixon’s Keynotes. The contributor adds, however, that there were always about three or four regular Wee Juns in the group, so it is clear that they were indeed a band rather than, say, a vocal duo or vocal group who always relied on others for musical accompaniment.

On 28 May 2011, an existing incarnaion of the Wee Juns were down to appear at a Montgomery Avenue, Sheffield 6pm-10pm street party called “Back To The Sixties On Saturday Night”, organised for charitable causes by David Johnson and the then Mayor of Sheffield, Ian Sanford. However, someone who visited the event has since told me they did not ‘show’.

Another traditional uncertainty that needs clearing up relates to the original thought that perhaps there was only one such-named group (in view of the apparent strangeness of their name) and that they went on to cut another record for the Skoop label. This is not the case at all.

Another traditional uncertainty that needs clearing up relates to the original thought that perhaps there was only one such-named group (in view of the apparent strangeness of their name) and that they went on to cut another record for the Skoop label. This is not the case at all.

Weejuns were a kind of slip-on loafer shoe, first manufactured in the States by the Bass Company, and much worn by ‘teens and twenties’ in the early sixties. It was then considered pretty ‘cool’ to wear weejuns and so it’s not surprising that the name was in fact adopted by several musical groups (usually ‘garage’ bands) of that era.

I have identified at least three other Wee Juns groups.

It was, in fact, a south west Indiana group of that name from the Evansville/Posey County area who cut the Skoop single, “Way Down”/”Without Your Love” (#1068). This forty-five was recorded at the Showboat Records studio in Santa Claus, Indiana (I kid you not!). “Way Down” appeared in 1998 on an album on the Teenage Shutdown label entitled, “She’ll Hurt You In the End, the Teener(sic) Garage Explosion, Vol. 2”.

Then we have a Battle Creek, Michigan set of Wee Juns, who cut “Ready C’mon Now” and “Girl”, although I don’t have label details.

Don Miller's Wee Juns

Don Miller's Wee JunsHowever, perhaps the best-known and most enduring group of Wee Juns were organised in Burlington, North Carolina by Don Miller, a local music-store proprietor, musician and label-owner, who also had ties with Atlanta. Miller’s store was called Don’s Music City and I believe it still exists at 1326 S. Church Street, Burlington, although it’s no longer run by Don.

Miller’s Wee Juns were founded as early as 1959 at Elon College in Burlington and evolved into a 5-piece band who became very popular with early-to-mid 60’s regulars on the Carolina Beach Music scene. Their first record was “If You Say Goodbye” in 1963. They also had their own ‘Theme’ and they cut a 45 of this, combined with their locally popular version of “Where Have You Been” (the Mann and Weil song best known via Arthur Alexander’s early Fame recording of it), this pairing emerging, together with a picture sleeve, in 1966 on Don Miller’s Jaguar label # DM 866, the DM prefix being Miller’s initials. This Wee Juns group appears to have folded in 1967.

With one side of the Quinvy Wee Juns’ 45 (“Out Of The Clear Blue Sky”) published by “Raleigh” music, seeing as the city of Raleigh NC is not all that far from Burlington, it’s still tempting to think that there might yet be some connection between this group of Wee Juns and Don’ Miller’s group; however this is not so and the explanation is quite simple - the writer of the song, namely local Shoals luminary Donnie Fritts, was contracted at the time to publishers Raleigh Music.

Re: Don Varner.

I mention above Don Varner’s original recording of “Home For The Summer”, cut probably around the Spring of 1967 and a little later released on South Camp 7005. However, I forgot to mention that this song was an Eddie Hinton/Marlin Greene creation and that Eddie, perhaps inevitably, cut a good demo of it, which you can find on that fine 2004 Zane ZNCD 1020 release, “Playin’ Around”.

Re: Mickey Buckins.

Mickey Buckins & The New Breed’s South Camp 7004 ‘A’ side was the driving Eddie Hinton song “Seventeen Year Old Girl”, which the label makes clear was produced by Hinton and Greene. However, the flip “Long Long Time” would appear at first look to be merely a reissue of Buckins’ self-penned song which appeared in 1966 as the flip of his “Silly Girl” on Norala 6603.

However, the South Camp 7004 “Long Long Time” label states that this performance was also a Hinton and Greene production. If that is correct, then I suspect the version of “Long Long Time” on South Camp is a newer version, since Eddie Hinton was not on the Quinvy ‘scene’ when Buckins’ earlier Norala version of that song was cut.

Back to article index | Top of Page