Quin Ivy And His Norala And Quinvy Studios, Part 6 – 1969

Regular session men leave for good – Sledge sales in decline - more visiting artists cut at Quinvy – white country-rock acts added to the mix.

January 1969 at Quinvy saw Bill Brandon cutting two songs on 23rd of that month, including a genuinely killer deep cut, though neither of these efforts saw release at the time, both having to wait for Charly’s 1989 “High On The Hog” CRB 1222 LP to find their way onto vinyl. A top team of studio session guys and gals was in evidence with Hinton, Greene, Hood and Hawkins making up the rhythm section, alongside the Memphis Horns and Ed Logan, plus Jeanie, Donna, Mary and Susan on back-ups.

Brandon’s self-penned ![]() One Minute Woman was a superb, lyrical lay-back deep winner, undeniably one of his finest-ever recordings which also boasted segments that allowed the emotion to build nicely, courtesy not just of Bill’s expressive vocal but also of some great horn and femme back-up support. One can’t also overlook the fine organ playing evident on the quieter passages and it seems likely that Barry Beckett was also in attendance.

One Minute Woman was a superb, lyrical lay-back deep winner, undeniably one of his finest-ever recordings which also boasted segments that allowed the emotion to build nicely, courtesy not just of Bill’s expressive vocal but also of some great horn and femme back-up support. One can’t also overlook the fine organ playing evident on the quieter passages and it seems likely that Barry Beckett was also in attendance.

“Little By Little”, was the other track recorded but it was something of a disappointment, the admittedly nice storyline being conveyed far too much via the spoken word with not enough meaningful singing from Bill in evidence. The format, though very lay-back, was decidedly more country-pop than country-soul and, to my ears, could just as easily have been sung by someone like Bobby Goldsboro.

“Little By Little”, was the other track recorded but it was something of a disappointment, the admittedly nice storyline being conveyed far too much via the spoken word with not enough meaningful singing from Bill in evidence. The format, though very lay-back, was decidedly more country-pop than country-soul and, to my ears, could just as easily have been sung by someone like Bobby Goldsboro.

Now, although we don’t have a Quin Ivy sheet for the then New York-based Judy White’s only session at his Quinvy studio, she is the daughter of bluesman Josh White to whom we alluded in our last Part and who delivered two superb pieces of soul, ![]() Satisfaction Guaranteed, courtesy of Hinton and Greene, and

Satisfaction Guaranteed, courtesy of Hinton and Greene, and ![]() I’ll Cry, penned by Judy’s fellow Buddah artist Barry Goldberg, which would go to make up both sides of her terrific forty-five on Buddah 79. As we said before, this session could have been held in late 1968 or early 1969 but it is clear that the single did not see release until early-ish 1969 (the last Buddah 45 to be issued in 1968 being Buddah 75). You can read more about Judy White here.

I’ll Cry, penned by Judy’s fellow Buddah artist Barry Goldberg, which would go to make up both sides of her terrific forty-five on Buddah 79. As we said before, this session could have been held in late 1968 or early 1969 but it is clear that the single did not see release until early-ish 1969 (the last Buddah 45 to be issued in 1968 being Buddah 75). You can read more about Judy White here.

Suffice to say here that Eddie Hinton’s riveting guitar intro to Judy’s

Suffice to say here that Eddie Hinton’s riveting guitar intro to Judy’s ![]() Satisfaction Guaranteed had also been similarly used on his own earlier very fine demo recording of his and Marlin’s song. There is a suggestion (which, from Eddie’s demo rather than from Judy’s released version, seems sensible to my ears) that Hinton and Greene penned this song originally with Joe Tex in mind. Tex never cut it but I am sure you will be able to imagine Joe singing this item as you listen to the MP3 of Hinton’s demo featured here, which incidentally you can find in full audio quality amongst many other good demos from Eddie on the excellent Zane CD “The Songwriting Sessions Volume 2” (ZNCD 1020).

Satisfaction Guaranteed had also been similarly used on his own earlier very fine demo recording of his and Marlin’s song. There is a suggestion (which, from Eddie’s demo rather than from Judy’s released version, seems sensible to my ears) that Hinton and Greene penned this song originally with Joe Tex in mind. Tex never cut it but I am sure you will be able to imagine Joe singing this item as you listen to the MP3 of Hinton’s demo featured here, which incidentally you can find in full audio quality amongst many other good demos from Eddie on the excellent Zane CD “The Songwriting Sessions Volume 2” (ZNCD 1020).

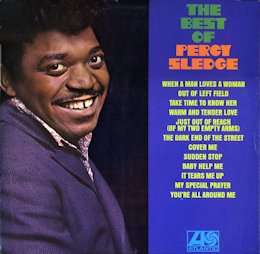

Early in the year Atlantic decided to release “The Best Of Percy Sledge” LP, a twelve tracker featuring most of his biggest career successes to date. The track-listing can be seen in our photo of the front-cover and the album on Atlantic 8210 entered the Billboard Top 200 Pop Album chart on 1st March where it remained for 11 weeks, peaking at No.133, whilst entering Billboard’s Top 50 R&B Album chart a week later for a 10-week stay, with a highest placing of No.27. This would prove to be Percy’s last original US Atlantic album.

Next, to some 1969 Quinvy recordings by two artists (one a Quinvy ‘regular’, Don Varner, and one a visitor, Ruby Winters) for which we again do not have session dates but which were probably all cut around March.

Next, to some 1969 Quinvy recordings by two artists (one a Quinvy ‘regular’, Don Varner, and one a visitor, Ruby Winters) for which we again do not have session dates but which were probably all cut around March.

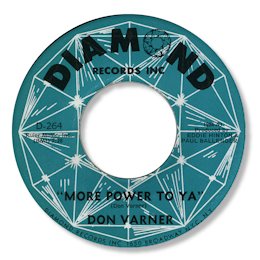

Don Varner was never signed to Quinvy but had an artist/writer contract with Hinton and Ballenger’s Ruler Music. His two 1969 recordings were once again Eddie And Paul’s productions, this time of his self-penned, almost jaunty-paced ![]() More Power To Ya and of Hinton, Fritts and Oldham’s impressive mid-pacer “Handshakin’”. This latter song would be cut again at Quinvy in March 1970 (see later Part) by Jimmy Braswell, who would also cover Varner’s South Camp 7005 outing from 1967, “Home For The Summer”. Both of Varner’s 1969 sides would be coupled on Diamond 264 in the late-summer of that year, this particular 45 being issued immediately before Ruby Winter’s first Quinvy-cut Diamond release on 265.

More Power To Ya and of Hinton, Fritts and Oldham’s impressive mid-pacer “Handshakin’”. This latter song would be cut again at Quinvy in March 1970 (see later Part) by Jimmy Braswell, who would also cover Varner’s South Camp 7005 outing from 1967, “Home For The Summer”. Both of Varner’s 1969 sides would be coupled on Diamond 264 in the late-summer of that year, this particular 45 being issued immediately before Ruby Winter’s first Quinvy-cut Diamond release on 265.

Ruby Winters was a Louisville native, raised in Cincinnati. She had already been contracted for a while to the New York-based Diamond label and had enjoyed four medium-sized R&B hits with them, two of which had also just crept into the bottom of the Hot 100. Her last pre-Quinvy single had only managed No.40 on the R&B chart so perhaps she went to Ivy’s studio to try something new by marrying her fairly uptown vocal style to that special sub-Mason Dixon ‘sound’.

Ruby Winters was a Louisville native, raised in Cincinnati. She had already been contracted for a while to the New York-based Diamond label and had enjoyed four medium-sized R&B hits with them, two of which had also just crept into the bottom of the Hot 100. Her last pre-Quinvy single had only managed No.40 on the R&B chart so perhaps she went to Ivy’s studio to try something new by marrying her fairly uptown vocal style to that special sub-Mason Dixon ‘sound’.

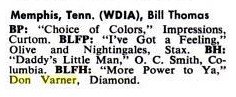

The first song recorded at Quinvy was ![]() Always David, a Dan Penn, Eddie Hinton, Wayne Jackson item to which Marlin Greene gave a fullish arrangement. Back in February 1969, The Sweet Inspirations had recorded the song as part of their “Sweets For My Sweet” Atlantic album (SD 8225) released on 20 June. This version had been cut at Fame with Arif

Always David, a Dan Penn, Eddie Hinton, Wayne Jackson item to which Marlin Greene gave a fullish arrangement. Back in February 1969, The Sweet Inspirations had recorded the song as part of their “Sweets For My Sweet” Atlantic album (SD 8225) released on 20 June. This version had been cut at Fame with Arif  Mardin and Tom Dowd of Atlantic overseeing things and Johnson, Hinton, Beckett, Hood and Hawkins in attendance. After Ruby had cut it, the song would be selected by Jerry Wexler to be part of his, Mardin’s and Dowd’s production on Cher for her Muscle Shoals Sound-recorded “3614 Jackson Highway” album (Atco SD33-298 – see shortly). In fact Wexler caught pneumonia, leaving Mardin and Dowd to do all the production work, and the song, though recorded, was not chosen for inclusion, the master tape itself soon getting lost.

Mardin and Tom Dowd of Atlantic overseeing things and Johnson, Hinton, Beckett, Hood and Hawkins in attendance. After Ruby had cut it, the song would be selected by Jerry Wexler to be part of his, Mardin’s and Dowd’s production on Cher for her Muscle Shoals Sound-recorded “3614 Jackson Highway” album (Atco SD33-298 – see shortly). In fact Wexler caught pneumonia, leaving Mardin and Dowd to do all the production work, and the song, though recorded, was not chosen for inclusion, the master tape itself soon getting lost.

Ruby Winters’ Quinvy version of “Always David” worked well enough for it to become a No.23 R&B hit in the fall of 1969 on Diamond 265, entering the chart on 27 September for a 6 week stay. The flip was Andy Badale (Angelo Badalamenti) and Jim Fragale’s “We’re Living To Give”, a song they had written earlier that year for “Hair” original cast member Melba Moore and which would appear on her debut solo LP “I Got Love” in 1970 on Mercury 61287.

However, Ruby’s other Quinvy-cut release, a revival of the 1959 Jesse Belvin hit “Guess Who” (coupled with Eddie Hinton’s uptownish beat-ballad “Sweetheart Things”) was an even bigger R&B hit, the single, on Diamond 269, entering  the chart on 13 Dec 1969 for a 9 week run, peaking at No.19. This 45 also scraped the bottom of the Hot 100 at No.99. (Incidentally some have thought this to be the same “Guess Who” as Ivory Joe Hunter’s hit back in 1949 but that was a different song, penned by Hunter’s wife, Beatrice, just as the Belvin/Winters song had been penned by Belvin’s wife Jo Anne).

the chart on 13 Dec 1969 for a 9 week run, peaking at No.19. This 45 also scraped the bottom of the Hot 100 at No.99. (Incidentally some have thought this to be the same “Guess Who” as Ivory Joe Hunter’s hit back in 1949 but that was a different song, penned by Hunter’s wife, Beatrice, just as the Belvin/Winters song had been penned by Belvin’s wife Jo Anne).

Ruby went on to record for Certron, Polydor, Playboy and Millenium in the 70s, having three further minor R&B hits, one for each of the last-three-named labels, although the Polydor and Millenium hits were both of “I Will”, the Millenium 45 being a reissue. She also had a 1978 album on Millenium named after her “I Will” hit which, although cut both in the Shoals and in Nashville, veered towards MOR. In the UK “I Will” had made No.4 on the Pop chart on Creole in late 1977 and she had further UK Creole hits which also found their way onto her final LP entitled “Songbird”, issued in 1979 on the UK budget K-Tel label (1045). A Rhino 22-track retrospective CD of Ruby’s work emerged in 1993 while a Pegasus “Best Of” CD appeared in 1999. A 29-track MP3 download collection was put out in 2007, also under the “Best Of” banner, and any Winters fans should still be able to find these tracks just by browsing the Amazon or I-Tunes sites.

Early April 1969 saw the return to Quinvy of local legend Percy Sledge for a 2-day session on 7th and 8th. This would be a landmark occasion, not particularly for the meagre three songs it produced, but because this would prove to be the last session at Quinvy for well over a year-and-a-half to feature any members of the rhythm players who had long been the regular backbone of Quin Ivy’s recorded output (that much later session would be another Percy Sledge one in December 1970 – see later Part). Messrs Hood, Beckett and Hawkins were indeed present for what would therefore be their penultimate Quinvy performance, and also in the studio were Hinton and Greene, a horn section and the usual 4-girl back up group.

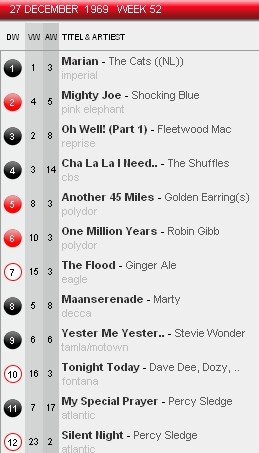

The year had started for Percy with his Atlantic 2594 forty-five of the March 1967-recorded “My Special Prayer” (see last Part) spending just four January weeks in the lowest reaches of the Hot 100 Pop chart, peaking at only No.93. Having left the Pop chart, strangely the record would then afterwards enter the R&B chart in mid-February for a three-week stint, peaking at No.44. A few days after Sledge’s April session at Quinvy his August 1968-recorded version of “Any Day Now” (Atlantic 2616 – see last Part) would enter the Hot 100 on 12 April for just 4 weeks, peaking at No. 86, whilst also spending 4 weeks on the R&B chart, although entering one week later and peaking at No.35.

The year had started for Percy with his Atlantic 2594 forty-five of the March 1967-recorded “My Special Prayer” (see last Part) spending just four January weeks in the lowest reaches of the Hot 100 Pop chart, peaking at only No.93. Having left the Pop chart, strangely the record would then afterwards enter the R&B chart in mid-February for a three-week stint, peaking at No.44. A few days after Sledge’s April session at Quinvy his August 1968-recorded version of “Any Day Now” (Atlantic 2616 – see last Part) would enter the Hot 100 on 12 April for just 4 weeks, peaking at No. 86, whilst also spending 4 weeks on the R&B chart, although entering one week later and peaking at No.35.

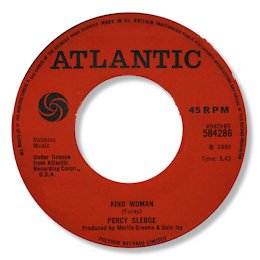

Sadly, the hits would now largely dry up for Percy and, although two of the three sides cut in April ’69 would see 45 release, saleswise they were a big disappointment. ![]() Kind Woman was a modern folk song penned by Richie Furay, an ex-Buffalo Springfielder and by now a member of Poco. It had appeared on the 1968 Springfield album “Last Time Around”. In Sledge’s hands, this ultra-slow, rather-too-dirge-like performance would creep to No.116 in the ‘bubbling under’ chart for just 2 weeks in August when coupled on Atlantic 2646 with Donnie Fritts, Carroll Quillen and Grady Smith’s “Woman Of The Night” (first recorded back in August 1968 – see last Part – but, according to the Sledge Rhino box-set, re-cut at a 27 May 1969 session, the date they also give for the recording of “Kind Woman”).

Kind Woman was a modern folk song penned by Richie Furay, an ex-Buffalo Springfielder and by now a member of Poco. It had appeared on the 1968 Springfield album “Last Time Around”. In Sledge’s hands, this ultra-slow, rather-too-dirge-like performance would creep to No.116 in the ‘bubbling under’ chart for just 2 weeks in August when coupled on Atlantic 2646 with Donnie Fritts, Carroll Quillen and Grady Smith’s “Woman Of The Night” (first recorded back in August 1968 – see last Part – but, according to the Sledge Rhino box-set, re-cut at a 27 May 1969 session, the date they also give for the recording of “Kind Woman”).

Ivy’s session sheet shows that the mid-paced “Push Mr. Pride Aside” was also cut on 7th or 8th April (the box-set specifies 4th June) and this track wouldn’t appear on Atlantic 2719 until 1970 when coupled with “Too Many Rivers To Cross” (which itself wasn’t cut till early in that year – see later Part). Sledge’s version was not as punchy as Eddie Bradford’s interpretation would prove in 1972, this performance also being cut at Quinvy (see later Part) and seeing release in that year on Chess 2133.

Ivy’s session sheet shows that the mid-paced “Push Mr. Pride Aside” was also cut on 7th or 8th April (the box-set specifies 4th June) and this track wouldn’t appear on Atlantic 2719 until 1970 when coupled with “Too Many Rivers To Cross” (which itself wasn’t cut till early in that year – see later Part). Sledge’s version was not as punchy as Eddie Bradford’s interpretation would prove in 1972, this performance also being cut at Quinvy (see later Part) and seeing release in that year on Chess 2133.

The title of the third and final song recorded by Percy at his April 1969 session is something of a mystery as the session sheet calls it “Bread And Water” but adds a question-mark afterwards as if a firm title had still to be agreed. Whatever it was eventually called, this performance was to remain ‘in the can’.

It was at this time, in early-to-mid-April, that Quin Ivy (and, for that matter, Rick Hall at Fame) said a sudden and doubtless largely unexpected farewell to their regular rhythm section of Johnson, Hood, Hawkins and Beckett. The soon-to-be Muscle Shoals ‘swampers’ recognised the important part they had played in creating both the Fame and the Quinvy sounds and reckoned they could earn more money for themselves by setting up their own studio than continually working for the rates Rick and Quin were paying. Bob Wilson noted the discontent as early as his first visits to Quinvy back in 1968 and comments:

“Quin was having some friction from the Florence/Muscle Shoals rhythm section and horns as they were wanting a piece of the action on all these hits they were recording (at Fame and Quinvy) and the producers didn't want to share. There was also the issue that Nashville was a big union town for the studio musicians and Muscle Shoals (and Memphis) were known for being non-union recording centres. The studio recording musicians in Muscle Shoals did not make the good wages that we made in Nashville, having to work more hours to make the same amount. So, there was that resentment as well.”

This dissatisfaction came to a head early in 1969 when it was further fuelled by the lack of any extra remuneration offered to the musicians by Rick Hall despite his brand new deal in March of that year with Capitol Records to distribute his Fame label which was about to provide him with far more funds than he had ever received previously from Atlantic. Also, Hall’s new allegiance with Capitol would not have endeared him to Jerry Wexler and, seeing that the re-locating ‘swampers’ were not likely now to make use of Quinvy either, Wexler, not wanting to lose access to the ‘good ole southern boys’ whom he regarded quite simply as the best players in the area, promptly agreed to significantly fund their new venture and ensure that it resulted in the creation of a then-state-of-the-art 8-track facility to tie in with the New York studios which Atlantic themselves regularly used.

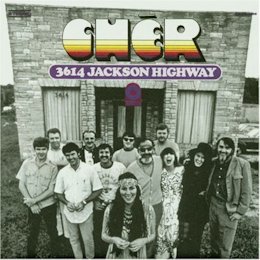

It had been back in 1967 that Jimmy Johnson had helped a certain Fred Bevis turn an old casket (coffin) warehouse opposite a cemetery at 3614 Jackson Highway, Sheffield into a 4-track recording studio. In 1968 Eddie Hinton had rented a room there where he penned some of his songs with Donnie Fritts. In late ‘68 or very early ‘69, Bevis decided he’d had enough and approached Roger Hawkins to see if he and Johnson would buy the studio from him. The duo soon convinced David Hood and Barry Beckett to join with them in this new venture, especially once Wexler had agreed to assist. Wexler would quickly benefit from the fruits of his involvement by bringing his Atco artiste Cher out from the West Coast to what would soon be called Muscle Shoals Sound in April 1969, just after the studio had opened. Cher began recording on 21 April (through to 30th plus a return on 14 May), cutting enough sides for her Atco album which would be named simply after the address of the new studio itself.

It had been back in 1967 that Jimmy Johnson had helped a certain Fred Bevis turn an old casket (coffin) warehouse opposite a cemetery at 3614 Jackson Highway, Sheffield into a 4-track recording studio. In 1968 Eddie Hinton had rented a room there where he penned some of his songs with Donnie Fritts. In late ‘68 or very early ‘69, Bevis decided he’d had enough and approached Roger Hawkins to see if he and Johnson would buy the studio from him. The duo soon convinced David Hood and Barry Beckett to join with them in this new venture, especially once Wexler had agreed to assist. Wexler would quickly benefit from the fruits of his involvement by bringing his Atco artiste Cher out from the West Coast to what would soon be called Muscle Shoals Sound in April 1969, just after the studio had opened. Cher began recording on 21 April (through to 30th plus a return on 14 May), cutting enough sides for her Atco album which would be named simply after the address of the new studio itself.

Although the ultimate success of MSS is now legendary, the start was not auspicious as Cher’s Atco 298 album was not commercially successful, only creeping into the national LP chart for a mere 3 weeks from mid-August, peaking at an unimpressive No.160, and spawning no big-hit singles.

Although the ultimate success of MSS is now legendary, the start was not auspicious as Cher’s Atco 298 album was not commercially successful, only creeping into the national LP chart for a mere 3 weeks from mid-August, peaking at an unimpressive No.160, and spawning no big-hit singles.

In addition to seeing hardly any more of his old rhythm-section ‘regulars’, Quin Ivy would not see much more either of his long-standing ‘partner’ Marlin Greene, who sold back his interest in Quinvy and, although he would still sit in for a few more Percy Sledge sessions in the future, Marlin, who had indisputably played a vital role in the whole Quinvy story thus far, would cease to be a permanent fixture at the studio. This was also true of Marlin’s friend Eddie Hinton who, in the event, would not undertake any more general session work at Quinvy. It was now David Johnson who was engineering (and overseeing) most everything, while Greene, Hinton and Ballenger migrated chiefly to Jackson Highway, at least for a while.

However, Ivy was still pulling in a certain amount of money from Wexler via his Sledge connection and he and David Johnson knuckled down to seek out other locally-available musicians to attempt to fill the distinguished shoes of the departed ‘swampers’. In this, they would initially receive some help also from their ‘Nashville connection’ man, Bob Wilson. (Fuller details about many of these ‘new recruits’ will feature in our next Part).

Phil Walden & Frank Fenter

Phil Walden & Frank Fenter It was at this very time that Z.Z. Hill, who had left the West Coast label Kent in 1968 after some four years with them, was put the way of Quin Ivy by Phil Walden, who had recently formed No Exit Records Inc. (the pre-cursor to what would soon become Capricorn Records). Apparently Hill was contracted to No Exit but no recordings were yet being made, which made Hill restless, so Walden sold the remaining time on Hill’s contract to Quin Ivy to start on the very day of Hill’s debut session at Quinvy, namely 31 May 1969. There was also some involvement somewhere in the chain from Bob Wilson, and either he, Ivy, Walden or Walden’s soon-to-be executive vice-president Frank Fenter (Atlantic’s ex Managing Director of European Operations) got Atlantic interested in leasing any good Hill material that might result from the liaison.

Wilson was to arrange Hill’s first session at Quinvy and he duly arrived there from Nashville, with bass-player Tim Drummond in tow. It would be on 31st May that he and Drummond would join with other musicians Don Walker, Jimmy Evans and Butch Owens to back-up Hill on what turned out to be the very fine, emotive, slow-paced, deep storyline-soul of ![]() (Home Just Ain’t Home At) Suppertime and the nicely-driving, rhythmic and slightly swampy foot-tapper “It’s A Hang Up Baby”, this latter item having been penned by singer/songwriter Eddie Reeves who had already seen Jerry Lee Lewis cut his song at American Sound Studios in Memphis for his otherwise chiefly Nashville-recorded 1967 “Soul My Way” Mercury 67097 album and would himself cut it in L.A. in 1970 on UA 50680.

(Home Just Ain’t Home At) Suppertime and the nicely-driving, rhythmic and slightly swampy foot-tapper “It’s A Hang Up Baby”, this latter item having been penned by singer/songwriter Eddie Reeves who had already seen Jerry Lee Lewis cut his song at American Sound Studios in Memphis for his otherwise chiefly Nashville-recorded 1967 “Soul My Way” Mercury 67097 album and would himself cut it in L.A. in 1970 on UA 50680.

Bob Wilson comments about the ZZ Hill session as follows:

“Quin wanted me to try to put together another rhythm section and horns to see if he could get a similar, commercial R & B sound (to the one achieved before the ‘swampers’ left) and I think these ZZ Hill cuts show that to be the case. Quin had been partnered with Marlin Greene, who played guitar, but he and Marlin were in the process of parting ways, so things were in a state of flux when I was there at Quinvy. At the time I was also working as a producer/arranger and musician for John Richbourg at Sound Stage 7 Records (SS7) and that Atlantic release on Z.Z. made John very nervous. He was deeply concerned that I was going to move down there and take part of the SS7 rhythm section with me. Anyway, I was very pleased with the ZZ Hill product, and so was Jerry Wexler at Atlantic. Quin told me that Jerry Wexler called him as soon as he heard the ZZ Hill cuts and was very excited by the product and the sound. He told Quin ‘that's the reason we (Atlantic Records) are down there with you’, and coming from Wexler, I took that as a big compliment. I also think maybe that some of the Shoals producers were trying to get more ‘up-town’ and, of course, the New York record labels already had plenty of sources to get that type product, but there was only one Florence/Muscle Shoals/Sheffield, and Atlantic wanted the traditional Shoals R&B ‘sound’ that delivered the hits. However, for some reason, Atlantic didn't push the promotion of that record, and we didn't get a hit. I was supposed to get co-producer credits together with Quin on the label and that was our deal, but later Quin told me that, politically, with Atlantic, he couldn't do it - because of their contract he (as ‘Quinvy’) had to be listed. So, I came out listed as arranger (on the label), which was accurate, and not co-producer, but that was cool, as I was very appreciative of the opportunity to work down there. I was very proud to be associated with Quinvy.”

“Quin wanted me to try to put together another rhythm section and horns to see if he could get a similar, commercial R & B sound (to the one achieved before the ‘swampers’ left) and I think these ZZ Hill cuts show that to be the case. Quin had been partnered with Marlin Greene, who played guitar, but he and Marlin were in the process of parting ways, so things were in a state of flux when I was there at Quinvy. At the time I was also working as a producer/arranger and musician for John Richbourg at Sound Stage 7 Records (SS7) and that Atlantic release on Z.Z. made John very nervous. He was deeply concerned that I was going to move down there and take part of the SS7 rhythm section with me. Anyway, I was very pleased with the ZZ Hill product, and so was Jerry Wexler at Atlantic. Quin told me that Jerry Wexler called him as soon as he heard the ZZ Hill cuts and was very excited by the product and the sound. He told Quin ‘that's the reason we (Atlantic Records) are down there with you’, and coming from Wexler, I took that as a big compliment. I also think maybe that some of the Shoals producers were trying to get more ‘up-town’ and, of course, the New York record labels already had plenty of sources to get that type product, but there was only one Florence/Muscle Shoals/Sheffield, and Atlantic wanted the traditional Shoals R&B ‘sound’ that delivered the hits. However, for some reason, Atlantic didn't push the promotion of that record, and we didn't get a hit. I was supposed to get co-producer credits together with Quin on the label and that was our deal, but later Quin told me that, politically, with Atlantic, he couldn't do it - because of their contract he (as ‘Quinvy’) had to be listed. So, I came out listed as arranger (on the label), which was accurate, and not co-producer, but that was cool, as I was very appreciative of the opportunity to work down there. I was very proud to be associated with Quinvy.”

Some have suggested that Hill had already been signed by Atlantic at this time but it seems this never happened at all, even though by September ’69 there was a report to this effect in Billboard, which also noted the release of Hill’s Atlantic 2659 single, featuring his two 31 May-recorded sides. However, in fact, as stated above, Hill was now contracted to the Quinvy Music Corporation and in early October Ivy would award Hill a full 3-day session which would result in no less than seven new tracks – a clear indication that, with Atlantic now interested in leasing Hill’s material, it would make sense for Ivy, David Johnson and Bob Wilson to try to keep that particular pot boiling and to produce more usable material from Quinvy’s talented ‘new’ blues and soul-man. We’ll come to these other Hill recordings shortly, when we reach October.

Some have suggested that Hill had already been signed by Atlantic at this time but it seems this never happened at all, even though by September ’69 there was a report to this effect in Billboard, which also noted the release of Hill’s Atlantic 2659 single, featuring his two 31 May-recorded sides. However, in fact, as stated above, Hill was now contracted to the Quinvy Music Corporation and in early October Ivy would award Hill a full 3-day session which would result in no less than seven new tracks – a clear indication that, with Atlantic now interested in leasing Hill’s material, it would make sense for Ivy, David Johnson and Bob Wilson to try to keep that particular pot boiling and to produce more usable material from Quinvy’s talented ‘new’ blues and soul-man. We’ll come to these other Hill recordings shortly, when we reach October.

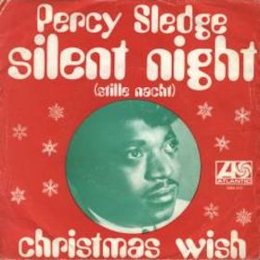

Now although many session dates given in this piece stem directly from Quinvy session sheets, not only are there many sessions (including demo sessions) which were certainly held at Quinvy but not shown on these sheets but also, not surprisingly, there are also a few anomalies. One such concerns Percy Sledge’s recording of two Christmas songs which would be paired on a  Netherlands-only Atlantic 54831 forty-five with the ‘A’ side reaching No.12 in that country’s Top 40 in December 1969. This was Percy’s take on the traditional carol

Netherlands-only Atlantic 54831 forty-five with the ‘A’ side reaching No.12 in that country’s Top 40 in December 1969. This was Percy’s take on the traditional carol ![]() Silent Night, which was coupled with “Christmas Wish”. Now in fact the Quinvy session sheets indicate these two songs were recorded in 1970 (not 1969) with the main reference being dated 8 October 1970 albeit both tracks have “cut track” side references showing dates in the previous month (September 1970). It seems very unlikely that these two songs were recorded again by Percy in 1970, as they were never issued that Christmas – or any other subsequent Christmas - in any other market, so it seems most likely that the dates on the Quinvy sheet simply show the wrong year and perhaps these two sides were recorded September/October 1969 – they certainly had to be cut around then for them to have been released in time for the 1969 Christmas market in Holland. This assumption is given added weight by the line-up of studio musicians on the session, as the names tie in with those used on other sessions at Quinvy around this Fall period of 1969, namely Jasper Guarino, Ronnie Oldham, Jimmy Evans and Butch Owens. The studio cut of “Silent Night” would later be overdubbed with an intro and some crowd noise for inclusion on the 1970 South African Atlantic LP “Percy Sledge In South Africa” (ATC 9257 - see last Part) and “Christmas Wish” would much later see its first CD issue on Rhino’s “R&B Christmas – Volume 3” (Cat No: 081227952860), released in Dec. 2004.

Silent Night, which was coupled with “Christmas Wish”. Now in fact the Quinvy session sheets indicate these two songs were recorded in 1970 (not 1969) with the main reference being dated 8 October 1970 albeit both tracks have “cut track” side references showing dates in the previous month (September 1970). It seems very unlikely that these two songs were recorded again by Percy in 1970, as they were never issued that Christmas – or any other subsequent Christmas - in any other market, so it seems most likely that the dates on the Quinvy sheet simply show the wrong year and perhaps these two sides were recorded September/October 1969 – they certainly had to be cut around then for them to have been released in time for the 1969 Christmas market in Holland. This assumption is given added weight by the line-up of studio musicians on the session, as the names tie in with those used on other sessions at Quinvy around this Fall period of 1969, namely Jasper Guarino, Ronnie Oldham, Jimmy Evans and Butch Owens. The studio cut of “Silent Night” would later be overdubbed with an intro and some crowd noise for inclusion on the 1970 South African Atlantic LP “Percy Sledge In South Africa” (ATC 9257 - see last Part) and “Christmas Wish” would much later see its first CD issue on Rhino’s “R&B Christmas – Volume 3” (Cat No: 081227952860), released in Dec. 2004.

Anyway, Percy’s emotive tones lent themselves well to the quiet serenity of “Silent Night” and one can readily appreciate the seasonal ‘appeal factor’ of the release.

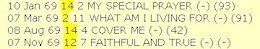

While his US sales were declining, Sledge’s star was shining pretty brightly not only in the Netherlands but also in South Africa. Here is a list of his South African single hits for 1969 (the first number after the date is the highest chart position that recording reached, while the second number is the number of weeks on chart. Numbers in brackets at the end of a line indicate the highest US Pop chart position that recording reached during its year of original US release).

On 11th September 1969 (according to the Rhino book-set) Percy cut his final version of a song he had already recorded in both April and August 1968 (see last Part), namely Aretha and Carolyn Franklin’s “Baby, Baby, Baby”, a song Ree had included on her “I Never Loved A Man The Way I Love You” Atlantic 8139 album back in 1967, as well as on an Atlantic 2441 forty-five. This somewhat dated-sounding and rather drab, slow ballad doesn’t sound too much like a typical Quinvy recording despite Messrs. Ivy and Greene producing (the box-set quotes the location simply as “Alabama”). It remained unissued at the time but finally first emerged on the “Atlantic Unearthed – Soul Brothers” Rhino CD8122-77625-2 in 2006.

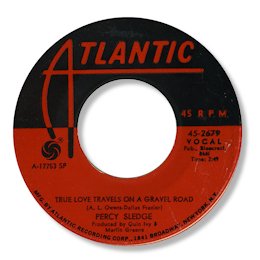

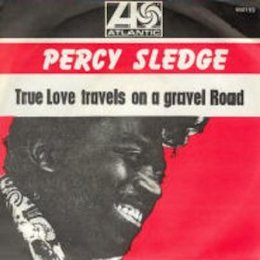

On 19th September 1969 (again according to the Rhino book-set) Percy cut

On 19th September 1969 (again according to the Rhino book-set) Percy cut ![]() True Love Travels On A Gravel Road. This song, penned by Nashville Music Row ‘regulars’ A.L. ‘Doodle’ Owens and Dallas Frazier, had been a No.62 national country hit for Duane Dee on Capitol 2332 back in December ’68, just before Elvis cut it at American Studios early in ’69 for his ‘come-back’ album “From Elvis In Memphis”, which was released that June. Presumably this is what prompted Ivy and a ‘returning’ Marlin Greene to cut this gentle mid-pacer on Percy. We can’t be certain that this track was actually cut at Quinvy (aurally it doesn’t sound like it, and the box-set simply quotes “location unknown”, yet we have to remember many ‘new’ country-honed musicians were now being used by Ivy and Johnson in place of the departed ‘swampers’ so there was also something of a ‘new’ Quinvy ‘sound’). Apart from the brass backdrop, the performance is almost more ‘country’ than ‘soul’. This underlined Quin Ivy’s long-term opinion (one he kept putting to Atlantic) that Percy was essentially a ‘country’ singer and regularly drew white country fans to his gigs. This song would be coupled with Marlin, Jeanie and Dan Penn’s excellent “Faithful And True” (originally recorded way back in June ’67 although Percy’s Rhino book-set indicates this was a re-cut version also from 19 September 1969) on Atlantic 2679 as the follow-up 45 to Percy’s “Kind Woman”. (However “Faithful And True” would be recorded yet again at Quinvy by the aforementioned Z.Z. Hill as early as the following month, October – see shortly).

True Love Travels On A Gravel Road. This song, penned by Nashville Music Row ‘regulars’ A.L. ‘Doodle’ Owens and Dallas Frazier, had been a No.62 national country hit for Duane Dee on Capitol 2332 back in December ’68, just before Elvis cut it at American Studios early in ’69 for his ‘come-back’ album “From Elvis In Memphis”, which was released that June. Presumably this is what prompted Ivy and a ‘returning’ Marlin Greene to cut this gentle mid-pacer on Percy. We can’t be certain that this track was actually cut at Quinvy (aurally it doesn’t sound like it, and the box-set simply quotes “location unknown”, yet we have to remember many ‘new’ country-honed musicians were now being used by Ivy and Johnson in place of the departed ‘swampers’ so there was also something of a ‘new’ Quinvy ‘sound’). Apart from the brass backdrop, the performance is almost more ‘country’ than ‘soul’. This underlined Quin Ivy’s long-term opinion (one he kept putting to Atlantic) that Percy was essentially a ‘country’ singer and regularly drew white country fans to his gigs. This song would be coupled with Marlin, Jeanie and Dan Penn’s excellent “Faithful And True” (originally recorded way back in June ’67 although Percy’s Rhino book-set indicates this was a re-cut version also from 19 September 1969) on Atlantic 2679 as the follow-up 45 to Percy’s “Kind Woman”. (However “Faithful And True” would be recorded yet again at Quinvy by the aforementioned Z.Z. Hill as early as the following month, October – see shortly).

Now, by 1969, country-rock music was selling well and Quin Ivy, David Johnson and Bob Wilson were aware that perhaps extra ‘bucks’ could be made by also embracing the recording of such music at Quinvy. In 1970 (see later Part), Lynyrd Skynyrd would visit there to cut some significant demos but even back in 1969 the emerging local rock scene left its mark on Quinvy, as I found out during one of my many internet searches.

Now, by 1969, country-rock music was selling well and Quin Ivy, David Johnson and Bob Wilson were aware that perhaps extra ‘bucks’ could be made by also embracing the recording of such music at Quinvy. In 1970 (see later Part), Lynyrd Skynyrd would visit there to cut some significant demos but even back in 1969 the emerging local rock scene left its mark on Quinvy, as I found out during one of my many internet searches.

I encountered a blog where David Johnson had written to the country-rock performer J.D. (Johnny) Wyker as follows: “Johnny, I found a box that says “Baby Ruth American Eagles”. Haven't been able to listen to it yet. Do you know what this is? – Bat Johnson.”

Wyker replied: “Hey Bat ! I can't believe you've actually found the long lost "Baby Ruth" tapes that we recorded at your studio in 1969! This is amazing and great, great news! I first started writing songs for Tom Stafford at Spar Music above City Drug Store in Florence in the late, late 1950's when I was barely a teenager but these tapes from 1969 relate to a session which was actually the first time I got up enough courage to try and sing one of my own  songs on tape! The truth is that I was broke at the time and you and Quin Ivy were kind enough, and ya'll had enough blind faith in me, to let me use your studio to record "Baby Ruth" and another song I wrote titled "On The Brighter Side Of It All". I rounded up a bunch of my friends who were also broke, unknown, and aspiring musicians to play on these cuts."

songs on tape! The truth is that I was broke at the time and you and Quin Ivy were kind enough, and ya'll had enough blind faith in me, to let me use your studio to record "Baby Ruth" and another song I wrote titled "On The Brighter Side Of It All". I rounded up a bunch of my friends who were also broke, unknown, and aspiring musicians to play on these cuts."

Wyker then goes on to name Wayne Perkins (see next Part) on guitar, Chuck Leavell (see later Part) on piano and Charlie Hayward on bass, while Lou Mullenix and Bill Connell shared drum duties. In 1972, when Wyker and Court Pickett had formed Sailcat, both Mullenix and Connell would drum on the duo’s “Motorcycle Mama” album (Elektra 75029) which would hit No.38 on the national album chart, having followed on from a summer 1972 No.12 national Pop hit-single of the same name on Elektra 45782. A later 1972 forty-five would feature the Muscle Shoals Sound-recorded version of the Quinvy-demo-ed “Baby Ruth” (Elektra 45817).

At the Quinvy sessions in 1969 it seems certain that demos for The American Eagles were put down too as Johnson says this name also appeared on the tape box he found. This group comprised Wyker, Leavell and John Bucky Wilkin – the ex Ronny of Ronny & The Daytonas who had enjoyed five Hot 100 hits between 1964 and 1966 including the million-selling 1964 No.4 hit “G.T.O.” on Mala 481. As early as the Fall/Winter of 1969, The American Eagles would release the original version of “Me And Bobby McGee” (written by Wilkin’s cousin and roommate Kris Kristofferson) on a Liberty 45 (no.56125) coupled with “The Nashville Sun”, albeit the actual issued material was again cut, not at Quinvy, but at Muscle Shoals  Sound. These sides and other American Eagles material would later see inclusion on the 1970 LP “In Search Of Food, Clothing, Shelter And Sex” (Liberty 7639), attributed solely to John Buck Wilkin. One track from the LP which had also been demo-ed at Quinvy, according to Wyker, was “Apocalypse 1969”, a song co-penned by Wilkin and Kristofferson.

Sound. These sides and other American Eagles material would later see inclusion on the 1970 LP “In Search Of Food, Clothing, Shelter And Sex” (Liberty 7639), attributed solely to John Buck Wilkin. One track from the LP which had also been demo-ed at Quinvy, according to Wyker, was “Apocalypse 1969”, a song co-penned by Wilkin and Kristofferson.

In 1985, it would be Wyker who would rescue a drunk and desolate Eddie Hinton from outside a Salvation Army Hostel, set him up in a one-room apartment in Decatur and co-produce with him at the local Birdland Studio six of the 12 songs which would make up Hinton’s “Letters From Mississippi” album.

By the Fall, Tony Borders’ earlier cuts of “You’d Better Believe It” and “Lonely Weekends” (see earlier Parts) were finally coupled together for release on Uni 55180; but next into Quinvy between 15th and 18th September 1969 was white country-rock ‘n roll/R&B man Buddy Causey, along with his sister Sandra, both sometime students of Jackson Miss. State Uni. Causey had another recent claim to fame too: he had just picked up a small part in what would become the cult ‘biker’ film “Easy Rider”, starring Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper and Jack Nicholson, scenes for which had been filmed locally. Causey was cast as one of the ‘rednecks’ in the supposed Louisiana coffee-shop who would taunt the ‘bikers’. The filmmakers had been preparing to audition a group of local actors when Dennis Hopper happened to notice Buddy Causey Jr., Duffy Lafont and several others watching them and making wisecracks and decided to use them to play the coffee-shop guys instead.

The main track Causey put down at Quinvy in September ’69 was a medley of “Hey Baby”, “39-21-46” and “I’ve Been Hurt” which got coupled with “I Had No Idea” on a 1970-issued Quinvy 7002 forty-five (see later Part). This pairing was also earmarked for Spring 1970 release on Atlantic 2718, though this forty-five seems rarer than hen’s teeth. However, Causey’s two-sider would indeed make another appearance in the middle of that year on UA 50684 (again, see later Part). Other Causey tracks cut in September 1969 were “Leaving Me Cold”, “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight”, “Isn’t It Lonely Tonight”, “Hey Little Lady” and “A Nice Place To Visit”, which Tony Borders had cut at Quinvy the previous October (see last Part). The session men used were Tippy Armstrong, Jasper Guarino, Jimmy ‘Be-Bop’ Evans, Ronnie Oldham and Butch Owens. Causey would re-appear at Quinvy in April 1970, after which he would form his own band (the first of many) and we’ll briefly summarise his later activity (which did include an unissued version of a famous James Brown song cut for David Johnson) after we discuss that 1970 Quinvy session in a later Part.

The main track Causey put down at Quinvy in September ’69 was a medley of “Hey Baby”, “39-21-46” and “I’ve Been Hurt” which got coupled with “I Had No Idea” on a 1970-issued Quinvy 7002 forty-five (see later Part). This pairing was also earmarked for Spring 1970 release on Atlantic 2718, though this forty-five seems rarer than hen’s teeth. However, Causey’s two-sider would indeed make another appearance in the middle of that year on UA 50684 (again, see later Part). Other Causey tracks cut in September 1969 were “Leaving Me Cold”, “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight”, “Isn’t It Lonely Tonight”, “Hey Little Lady” and “A Nice Place To Visit”, which Tony Borders had cut at Quinvy the previous October (see last Part). The session men used were Tippy Armstrong, Jasper Guarino, Jimmy ‘Be-Bop’ Evans, Ronnie Oldham and Butch Owens. Causey would re-appear at Quinvy in April 1970, after which he would form his own band (the first of many) and we’ll briefly summarise his later activity (which did include an unissued version of a famous James Brown song cut for David Johnson) after we discuss that 1970 Quinvy session in a later Part.

When Z.Z. Hill returned to the Quinvy Studio on 7th October for a three-day session, things were still OK between him and Quin Ivy. Hill’s first Atlantic 45 had not long been issued and the fact that ultimately it would fail to see much ‘push’ by Atlantic and would not achieve great sales was not yet known to either party. Indeed, Hill had reasonable expectations that, via Ivy, he might at last break through to the ‘big time’ in terms of record sales thanks to some good production of his undeniable talent at a soulful southern studio, duly promoted to a wider audience by a major label (Atlantic). One has to remember that, despite having been a regular ‘live’ attraction for some years, Hill at this time had absolutely no hit parade track-record at all (one solitary M.H. 45 back in early ’64 spending one equally solitary week at the very foot of the Pop and R&B chart was the sum total thus far!).

Hill clearly wanted ‘better’ and no less than seven tracks were put down from which to try to find the one song which would give him a hit on Atlantic. As we now know, all this optimism would prove to be misplaced. Atlantic would ‘drop’ Hill, not even releasing the single of “Faithful And True” and “I Think I’d Do It” which they had provisionally earmarked from the October Quinvy session for issue on Atlantic 2711, a release awarded instead to Mighty Sam’s “Your Love Is Amazing” and “Evil Woman”. A doubtless distraught Ivy would in the event push the single out half-heartedly in 1970 on his own Quinvy logo (No.7003 – see later Part) but, as a result, Hill would fall out with Ivy and would temporarily return to his brother Matt’s ‘fold’ where he would cut a record for his label which would finally see him do well in the charts. However, Hill’s continued regular appearance in the hit listings would be down to another producer, Jerry ‘Swamp Dogg’ Williams, who, ironically, would achieve that success by bringing Hill back to Quinvy in 1970, on the specific understanding that Ivy would not personally attend the sessions (see later Part).

Hill clearly wanted ‘better’ and no less than seven tracks were put down from which to try to find the one song which would give him a hit on Atlantic. As we now know, all this optimism would prove to be misplaced. Atlantic would ‘drop’ Hill, not even releasing the single of “Faithful And True” and “I Think I’d Do It” which they had provisionally earmarked from the October Quinvy session for issue on Atlantic 2711, a release awarded instead to Mighty Sam’s “Your Love Is Amazing” and “Evil Woman”. A doubtless distraught Ivy would in the event push the single out half-heartedly in 1970 on his own Quinvy logo (No.7003 – see later Part) but, as a result, Hill would fall out with Ivy and would temporarily return to his brother Matt’s ‘fold’ where he would cut a record for his label which would finally see him do well in the charts. However, Hill’s continued regular appearance in the hit listings would be down to another producer, Jerry ‘Swamp Dogg’ Williams, who, ironically, would achieve that success by bringing Hill back to Quinvy in 1970, on the specific understanding that Ivy would not personally attend the sessions (see later Part).

In truth, there was little wrong aesthetically with much of the material Hill laid down at Quinvy back in October ’69 and, like so much fine soul cut there (Sledge’s hits notwithstanding) it is really amazing that such music failed to succeed commercially. Marlin, Jeanie and Dan Penn’s “Faithful And True” hadn’t received much promotion when issued as one side of Sledge’s Atlantic 2679 single and Hill’s version was, if anything, superior. “I Think I’d Do It” was a good funky piece of driving blues-soul penned by the great Sam Dees and this pairing should have made for a successful forty-five. “Hold Back (Give Your Love To One Man At A Time)” was a first-rate piece of layback storyline country-soul. “Early In The Morning” was a re-make of the old Bobby Darin song also favoured by Ray Charles, the piece starting slowly before changing to a fast-paced tempo. “Touch ‘Em With Love” was almost more pop than soul and not outstanding. Also not very impressive was Z.Z’s take on Jimmy Holiday and Jackie de Shannon’s pop song “Put A Little Love In Your Heart”. Hill’s version lacked the spark that this song of optimism required. Penn and Oldham’s ![]() Take Me (Just As I Am), however, was taken at an ultra-slow pace, which if anything only served to underline the poignant beauty of this fine song. Hill’s interpretation is outstanding for me, with a good emotional climax adding to its ‘deep’ quality, and it certainly rivals those other great versions by the likes of Arthur Conley and Spencer Wiggins. As on the recent Buddy Causey dates, the session men used were Jasper Guarino, Jimmy ‘Be-Bop’ Evans, Ronnie Oldham and Butch Owens, with Tippy Armstrong this time apparently missing. (Remember, we shall be giving more biographical information about many of these ‘post-Swampers’ Quinvy session-men in our next Part).

Take Me (Just As I Am), however, was taken at an ultra-slow pace, which if anything only served to underline the poignant beauty of this fine song. Hill’s interpretation is outstanding for me, with a good emotional climax adding to its ‘deep’ quality, and it certainly rivals those other great versions by the likes of Arthur Conley and Spencer Wiggins. As on the recent Buddy Causey dates, the session men used were Jasper Guarino, Jimmy ‘Be-Bop’ Evans, Ronnie Oldham and Butch Owens, with Tippy Armstrong this time apparently missing. (Remember, we shall be giving more biographical information about many of these ‘post-Swampers’ Quinvy session-men in our next Part).

Despite Bob Wilson’s involvement with Ivy, back in Nashville the new branch of Quinvy was sadly proving a largely unsuccessful venture. Ivy duly wound it up and wanted Wilson to re-locate to Sheffield but Wilson declined. Bob comments on the situation as follows:

“Quin had wanted me to act as a sort of a talent scout for him in Nashville, for talent that we could bring to Quinvy to record. He had also been very interested in me pushing his songwriter catalogue in Nashville with the Country labels and producers. Because I was also working on lots of the Country hits as a studio musician and knew all the big Nashville record producers, he thought I could place some of his songs. But it was very tough. Lots of his best material (his R&B hits) were not in his own company's publishing or copyright area. The songs that he did have were not the strongest, and in Nashville, the competition to place hit-songs was ‘fierce’; there were gifted song-writers walking the streets up there, with hit songs falling out of their pockets. And, I felt that there was a ‘resistance’ when I was plugging the Quinvy material in Nashville. They were very aware of what was going on down there creatively and I think it raised some deep insecurity. Several of the major players in Nashville were originally from that part of Alabama and they all knew each other from ‘way back when’ and maybe they had some kind of personal history that made them shy away. There was also resentment by the union musicians in Nashville that Muscle Shoals (as mentioned earlier) was known for being a non-union recording centre.”

“Anyway, pushing Muscle Shoals material in Nashville had been very hard, much harder than I expected. One reason it didn't stick was that I was personally starting to ‘happen’ in Nashville and I really didn't want to move down there (to Sheffield), which was what Quin wanted. I was now working on the Bob Dylan and other pop recordings in Nashville and I had just joined the original Charlie Daniels Band along with my songwriting partner Billy Cox, so I was just too busy to keep it all going. Also, John Richbourg really sweetened my deal with SS7 Records, trying to keep me from producing for Quinvy (and Excello, as it happens) so, I had to give up my connection with Quin. Quin was a very cool guy but he was also a successful businessman with other financial interests that were dragging him away from the record business. It seemed to me that he was getting burned out trying to deal with Atlantic and all the New York boys.”

Still, even although Ivy had to close his Nashville ‘office’, at least he hadn’t made the even more major mistake of trying to open a full studio in another ‘music capitol’, a mistake Rick Hall would make that year when, largely funded by his new distributors Capitol, he set out to build an exact replica of his Fame Shoals-based studio at 1740 South Bellevue in Memphis (a continuation of Elvis Presley Boulevard). The studio would open in 1970 under the day-to-day control of Sonny Limbo. It lasted only about 18 months and Rick Hall was already trying to offload it by January 1972, when he placed a sales ad to that effect in Billboard.

One more 1969 session at Quinvy needs noting – it is assumed this took place, probably late in the year, though some sources suggest it could just have edged into 1970 – we cannot be sure. However, it duly produced the two tracks which would make up Kip Anderson’s rare Eydie single (so rare I can’t find anyone who even knows its issue number, although another single did appear on Eydie, namely Butch Patrick’s "I've Lost My Woman/ Funky Charge" on Eydie 8-9134).

One more 1969 session at Quinvy needs noting – it is assumed this took place, probably late in the year, though some sources suggest it could just have edged into 1970 – we cannot be sure. However, it duly produced the two tracks which would make up Kip Anderson’s rare Eydie single (so rare I can’t find anyone who even knows its issue number, although another single did appear on Eydie, namely Butch Patrick’s "I've Lost My Woman/ Funky Charge" on Eydie 8-9134).

As mentioned in Kip’s own page on this web-site, Quin Ivy had been impressed with his work at Fame and had invited him down for a session which produced the melodic if rather repetitive

As mentioned in Kip’s own page on this web-site, Quin Ivy had been impressed with his work at Fame and had invited him down for a session which produced the melodic if rather repetitive ![]() Abide In Me and the almost frenetic “Frozen Heart”, neither of which sadly were really up to the quality of some of his earlier output. These two tracks would also appear on a rare LP, "The Best of Kip Anderson and The Soul Aggregation" (Eydie 10238/10239) which was also issued back in 1970, the track-listing for which you can see on Kip’s artist page. However, the extra (non-45) tracks which made up the LP were not cut at Quinvy but probably either in Fayetteville or some other North Carolina studio. Most of these Eydie tracks would appear on a 2009 Ripete ‘download only’ set of MP3s of Anderson material entitled “Say It One Time For The Broken Hearted”.

Abide In Me and the almost frenetic “Frozen Heart”, neither of which sadly were really up to the quality of some of his earlier output. These two tracks would also appear on a rare LP, "The Best of Kip Anderson and The Soul Aggregation" (Eydie 10238/10239) which was also issued back in 1970, the track-listing for which you can see on Kip’s artist page. However, the extra (non-45) tracks which made up the LP were not cut at Quinvy but probably either in Fayetteville or some other North Carolina studio. Most of these Eydie tracks would appear on a 2009 Ripete ‘download only’ set of MP3s of Anderson material entitled “Say It One Time For The Broken Hearted”.

The Eydie label had been named after the daughter of the owner of a music store in downtown Fayetteville, North Carolina called Eddie Monsour, who put up the cash for the Quinvy session. Fayetteville NC is where the South Carolina-raised Anderson relocated in order to supplement his income by becoming a DJ on the local 1600 AM WIDU radio station, which had changed from a Top 40 to a soul and gospel format in 1965. Kip had many contacts there and the music store in question was Eddie’s Music Center at 225 Hay Street (the buildings which housed the store and also the adjacent Dixie’s Billiards/Pool Hall are both now long gone and instead form part of the Cameo Art House Theater, the original building on this site having been Dixie’s, which had been the first-ever theater in Fayetteville, built in 1914). Eydie herself still lives locally, now known as Eydie Monsour Hammaker.

In our next Part, we’ll feature a closer look at the ‘new’ session musicians who played at Quinvy post-April 1969 and throughout 1970 in what otherwise would have been the considerable vacuum left by the departed ‘swampers’ plus Hinton and Greene.

UPDATE ~ Tony Rounce has written to say that "One Minute Woman" was written by the Bee Gees, and first recorded by them on their debut UK LP "Bee Gees First" in 1967. Thanks to Tony for putting the record straight.

UPDATE ~ Tony Rounce has written to say that "One Minute Woman" was written by the Bee Gees, and first recorded by them on their debut UK LP "Bee Gees First" in 1967. Thanks to Tony for putting the record straight.

However, there were also two other British-recorded versions of the song released before Bill Brandon somehow got hold of it.

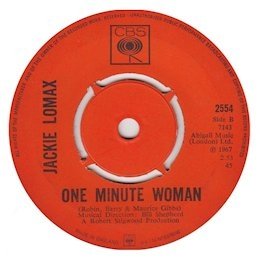

The song was first covered by the UK's Jackie Lomax on the 'B' side of his UK CBS 2554 single "Genuine Imitation Life" (released in October 1967) and then by the UK's Billy Fury on the 'B' side of his UK Parlophone R.5681 single "Silly Boy Blue" (itself a David Bowie 'cover' released on 22nd March 1968), even this release appearing some 10 months before Bill Brandon recorded his soul version at Quinvy.

FURTHER UPDATE

Tony Rounce has in his possession a South African 45 of Percy Sledge’s “Silent Night” and “My Christmas Wish For You” on S.African Atlantic ATS 480. My assertion above that this was a Dutch-only release is therefore clearly incorrect. Tony says: “it came out in a special sleeve - not really a pic sleeve; it was basically just a white bag with 'Percy Sledge' and 'Silent Night' printed on one side and 'Percy Sledge' and 'My Christmas Wish For You' on the other.

The label indicates a 1969 release, the record being clearly aimed at the same year’s Christmas market as the Dutch release. Thanks Tony, for this ‘new’ information.

NEW FURTHER UPDATE ~

Don Varner’s 1969 Quinvy recording of Eddie Hinton, Donnie Fritts and Spooner Oldham’s “Handshakin’” (also to be cut in March 1970 at Quinvy by Jimmy Braswell – see Part 8) was pre-dated by an unissued Fame recording of the song by Ben & Spence, who hailed from Pensacola, Florida and arrived at Fame in the wake of fellow-Floridians James & Bobby Purify. Their recording of the song came in 1968 and has now seen release on UK Kent’s “Hall Of Fame” CD (CDKEND 372)..

The Purifys were cousins James Purify and Robert Lee Dickey and when Dickey left the duo in the late 60’s, James carried on as a solo for a while but when the duo was later ‘re-formed’, it was Ben Moore (the ‘Ben’ of Ben & Spence) who joined James as his new ‘Purify’ singing partner.

Acknowledgements: John Ridley; Peter Guralnick; Barney Hoskyns; Charles Fuqua; Gilles Petard; Colin Escott; Roben Jones; David Cole/In The Basement; Clive Richardson/RPM-Shout; Gary Cape/Paul Mooney Grapevine-Soulscape; Peter Thompson/Zane Records; Soulful Kinda Music; www.carolinasoul.org; Vintage Soul fanzine; Billboard; Rick Clark/Lynyrd Skynyrd Boxset Booklet; Chris Kuenzel of the Cameo Art House Theater Fayetteville; the websites and blogs of many of the artists/personalities featured.

Peter Thompson for his kind permission to use the Eddie Hinton demo of "Satisfaction Guaranteed" here. Peter's Zane label has issued several wonderful CD collections of Eddie's work - buy them.

Special thanks to Bob Wilson for his most welcome input.

Paul Mooney - All licensing enquiries for Quinvy / South Camp / Broadway Sound masters should be directed to Selrec Ltd and most of the songs are controlled by Millibrand Music Ltd in all territories outside the US and Canada.